5 Dark Realities Of Living Through The 1980s AIDS Crisis

An HIV diagnosis is no longer a death sentence in the Western world, so it's easy to forget that the so-called "gay plague" felt like the end of the world at one point. We had a sneaking suspicion that the reality of watching all your friends die from a mystery disease was a lot more disturbing than Rent let on, so we spoke to "Peter," an HIV-positive gay man who lived in San Francisco at the height of the AIDS crisis, back in the late '70s and early '80s. He told us ...

The Pre-AIDS Gay Scene Wasn't a Constant Orgy

You may want to sit down for this: There may not be as much sex in something as Hollywood has implied.

"One characterization I've always found inappropriate is the notion that pre-AIDS gay culture was a period of nonstop sex and that the epidemic brought that all to a screeching halt," Peter says. "In reality our lives were more varied and the change was more subtle and non-immediate (for example, SF's bathhouses didn't close until 1984), and even life in the urban gay ghettos was more complex than some of today's romanticized depictions imply. And while it's true that many of us tended to plan our lives around sex (or availability for sex), that didn't just vanish in 1981."

Planning your life around sex while not having as much as Hollywood suggests is normal? So young single people, basically.

You have to understand that being a gay man in San Francisco in 1980 was, well, a lot like being a gay man in San Francisco now.

"Hardly anybody was arriving in SF as a novice; it was like the graduate school of gayness," Peter says. "I established a routine that filled most of my free evenings (and invariably all of my weekends) with a very deliberate schedule for people watching, gym visits, and looking for sex. This created a huge amount of emotional momentum, and when the AIDS crisis arrived, that momentum didn't just disappear. It's not easy to suddenly halt energy-intensive habits like these. Some men I know who tried to -- basically swearing off everything that had defined their leisure time -- were, ironically, among the first I knew to get sick."

Well if you're damned if you bone and you're damned if you don't bone, we know how we'd vote.

So what did change?

"The baths closed, though not immediately," Peter says. "Video rentals (especially porn) took off. People got sick. People got scared. People got careful. People got (more) political. But the bars and dance clubs, with a few extremes curtailed, continued to operate, mostly as they had, with their numbers declining only very gradually."

All in all, "walking through the Castro on a Saturday afternoon in 1981-1982, one would not notice a big difference when compared to the same scene in 1979-1980, except for AIDS-related posters, leaflets, and political tabling (side by side with non-AIDS-related posters, leaflets, and tabling)."

You could still see a lot of varied stuff in the Castro District is really the point.

Which is not to say that the crisis wasn't a big deal, just that popular depictions of the scene were, as usual, mostly wrong. Peter remembers "comments from some in the straight world ... expressing surprise that our culture hadn't shut down. A reporter from one local news station, filming at a special dance event, remarked that the crowd was 'unexpectedly' festive. What the hell had she expected? Shrouds and lamentations? Her clear implication was: Gays are all about sex, dancing leads to sex, and sex leads to AIDS, so why are you crazy homos still dancing and, yknow, being all gay?"

Mass Death Quickly Became Routine

It's amazing how adaptable human beings are. Your neighborhood gets hit with the plague this week and it's all lamentations and wailing. But fast forward a few weeks and there's you, calmly donning your bird mask and checking the Google Playgue app to see where the death wagon is today and how badly it'll affect your commute. For Peter, dealing with death became as routine as reading the newspaper. Literally:

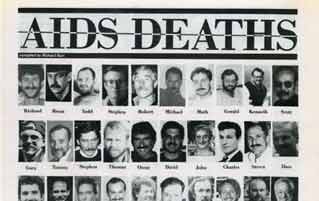

"The local gay paper published obituaries each week, and I'd check them carefully," Peter says. "Clearly that's a case of either no news or bad news, but I figured it was better to learn someone had passed from reading a news page than to get the news in a more sudden, unpleasant way -- like phoning him after a period of non-contact and hearing his roommate tell you he's dead and start to cry (which happened to a friend of mine). I even did my obit scans during the workday, grabbing the paper in a local bar where I'd stop after lunch."

The obituaries would get longer and longer as AIDS went on to become the leading cause of death among young men.

A lot of free time had to be sacrificed for hospital visits and memorial services, but eventually, Peter says, he "merged them into my schedule like haircut appointments." He's proud to report that he "never decided against" attending a funeral, and on only one occasion was he forced to send his regrets ...

... because it conflicted with a different funeral.

There Was A Very Real Possibility Of Gay Concentration Camps

The government's response to the AIDS crisis was infamously terrible. Former President Bush, Sr. once "responded to a reporter's question on HIV research with the insipid comment that most people don't approve of 'that lifestyle,' implying that funding HIV research wasn't a priority," recalls Peter. It could be worse: Reagan's White House press secretary Larry Speakes once mockingly implied that another reporter who pressed the issue must be gay himself, to even care.

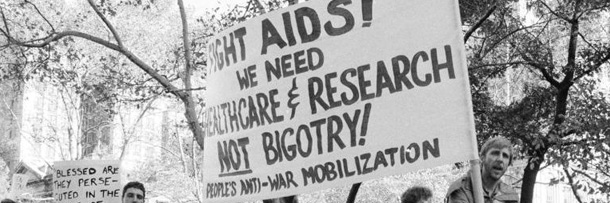

That kind of allergy to action is despicable, but at least they weren't campaigning for concentration camps, like California's Proposition 64, sponsored by the Prevent AIDS Now Initiative Committee. Yes, they actually called themselves "PANIC," presumably because "Early Virus Identification and Liquidation" was taken. PANIC insisted that all they wanted to do was add AIDS to the CDC's list of communicable diseases, but public health authorities warned that PANIC was downplaying the consequences of this, including mandatory testing and mass quarantine.

"The lack of trust that this engendered is probably hard for today's gay community -- who sees things like public billboards for antiviral meds -- to picture," Peter says. "The idea that you might also be consuming outright lies, or worse, envisioned for mass quarantine was a source of needless extra anxiety ... I rarely hear it mentioned today, but it was regarded as a near-mainstream position for some in the 1980s, not a crackpot fringe view as it is now."

It's not hard to imagine the people laughing at 4,200 deaths in that video shrugging if the barbed wire fences came out.

Ironically, those panic-driven measures probably exacerbated the epidemic. As Peter points out "the buildup to Prop 64 in California must surely have caused lots of people to forgo testing for fear of eventual quarantine ... Even now, HIV testing by public health agencies is anonymous -- at least when done right -- to safeguard against discrimination. In the early years when confidentiality was less certain and discrimination laws still weak, there were stories of people being fired after their bosses learned they'd merely gone to be tested."

Peter also recalls that "some physicians openly hostile," so there was always the risk that your own doctor might tell your employer just to spite you.

With No Official Treatment, "Alternative" Medicine Took Up The Cause

"One other thing that isn't mentioned much in the early years -- again, due mainly to the inaction of those in power and the consequent dearth of options -- a fair number of us looked into 'alternative treatments,'" Peter says. One of the more unsettling of these treatments was "a therapy called DNCB, which is an industrial solvent (!) applied to a patch of skin each week (that is, a burn) in an attempt to stimulate the immune system," Peter says. "Today, that's ridiculous on the face of it, but at the time, the feeling among adherents was basically: it might help, and there's nothing else I'm willing to try. I tried various less-invasive things, but nothing anywhere near as memorable."

Fight Club-style voluntary chemical burns notwithstanding, Peter insists that "the alternative treatments period wasn't worthless." The staff of the alternative medicine buyer's club he frequented were "friendly and supportive," which patients badly needed, and "although it probably helped sell a lot more questionable-value supplements than if HIV had never surfaced, it also educated a lot of people about milder ways to treat some symptoms."

I.e. non-burny.

For example, "it caused me to stumble over a no-downsides treatment for peripheral neuropathy -- an unpleasant side-effect of some HIV meds -- which I still use today, namely cod liver oil and L-carnitine. I found this in an amateurish treatment 'journal' (of which there were dozens) that I'm sure I otherwise never would have sought out."

It's not exactly advisable, but if another sex-plague breaks out in the near future, you can go ahead and take your health tips from a sketchy 'zine, too.

There's No Such Thing As A Long-Term Plan When You're Sure You're Going To Die

Hey, just out of curiosity, how's your IRA coming along? What, you don't have an IRA yet? That's a problem for "future you" to deal with? The young men in the midst of the AIDS epidemic felt the same way. Peter recalls that "the palpable threat of possibly never reaching middle age, let alone retirement, caused a lot of us to shut out that whole vision." So they did the completely logical thing and lived like they were gonna die young. "After my own diagnosis, I assumed I'd never even make it to Y2K, so while I didn't max out my cards like some guys, I saw no point in accumulating savings," Peter says.

By the '90s, medical science had revolutionized HIV treatment. It appeared that they might not die after all, and that left a lot of men in a precarious situation: "After the superdrugs arrived in the mid-1990s, a running joke acknowledged this peculiar situation -- thousands of men in their 40s or 50s with no nest egg suddenly realizing they'd survive -- saying 'It's great that we're all gonna live, but it sure is gonna fuck up a lot of plans,'" Peter says. "Viatication (a choice offered to some types of policyholders during the death-sentence era that works much like a reverse mortgage, where your life insurance benefit is paid to you while alive) made news often in the early 1990s, and spawned a lot of predictable jokes about who'd go bankrupt if the cure arrived tomorrow."

The punch line of course being "Who the fuck cares if thousands of people get to live."

At the time these treatments became available, Peter was in bad shape and began preparing for the worst. "My concern, obviously, was comfort and stability for whatever time I had left, not retirement," he says. "HAART changed all that." On the one hand, his improvement was nothing short of miraculous, even allowing him to return to work. On the other hand, "for a while, it didn't even register that I now had to devise a strategy and goals." A lot of scrambling to make up for lost time has helped Peter stabilize his finances, but "it's not nearly what an ordinary 60-year-old should have," he says. "I'm still expecting to be able to stay in my home when I retire and not starve. That said, I'll never be taking a cruise or flying overseas. I don't own a car."

Well hey, look on the bright side, Peter: There's still an off chance the Yellowstone Caldera could go super-volcano, or there's runaway climate change and hyper storms, obviously we got asteroid impacts, and the robot scourge is looking pretty promising these days ...

Manna has a Twitter sometimes.

For more insider perspectives, check out 5 Realities Of Life When You Know You're Going To Die and 6 Surprising Ways Life Looks Different With Terminal Disease.

Have a story to share with Cracked? Email us here.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel, and check out The Horrifying Truth About Those People In TV Commercials, and other videos you won't see on the site!

Also, follow us on Facebook, and let's be best friends forever.

Every year we're inundated with movies that are based on true stories. We're about to get a Deepwater Horizon movie where Mark Wahlberg will plug an oil spill with his muscles, and a Sully Sullenberger movie where Tom Hanks will land a plane on the Hudson with acting. But we think Hollywood could do better than this. That's why Jack O'Brien, the Cracked staff and comedians Lindsay Adams, Sunah Bilsted, Eli Olsberg, and Steven Wilber will pitch their ideas of incredible true stories that should be made into movies. Get your tickets for this LIVE podcast here!