When Hollywood Needs A Made-Up Language, They Come To Us

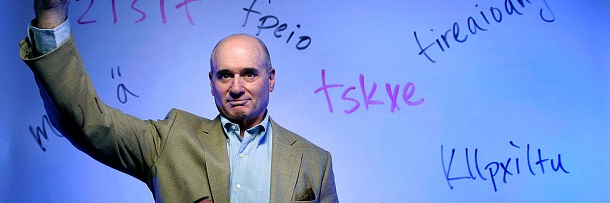

What's your favorite part of big-budget fantasy epics? The swords? The magic? The ... made-up languages their characters speak? If you inexplicably cheered for that last one, you might have a bright future as a conlanger -- a person who invents fictional languages for movies and TV shows. We're just as nerdy as you, so we sat down with David Peterson, the creator of Dothraki and Valyrian on Game Of Thrones, and Dr. Paul Frommer, the creator of Na'vi in James Cameron's Avatar, and learned that ...

There's No Career In Constructing Languages

For decades, Hollywood was perfectly happy with aliens and fantasy characters speaking perfect English, mostly with a British accent. But slowly we nerds began to demand more, and now any serious production with lasers/dragons/laser-dragons has to feature its own fictional language. How many people can invent a language out of nothing? The amount of work that takes sounds insane - they must make a small fortune.

A very, very small fortune.

"There's a greater demand for professional language creation services in Hollywood than there's ever been," Peterson explains, "but that still means there's about five jobs a year out there. Furthermore, if you are contacted, you're not just negotiating for your pay; you're defending the job itself. At a certain price point (a point which varies so wildly it can't even be estimated), the producers will decide it's simply not worth it to have a created language at all. You're competing against them saying, 'Let's just have them speak English.'"

Competing with human laziness doesn't often end well. Also not helping is the fact that Hollywood deals only in extremes: They only want to hire either the most experienced conlangers or complete amateurs.

"When producers need someone to create a language," Peterson says, "they first look for people they've heard of, but language creators are absolutely unheard of -- unless they've worked on a major production like Avatar or Game Of Thrones. A new job, then, will either go to someone who's already done a huge job (or several), or it will go to someone handy -- likely no one who's ever before considered creating a language ..."

Hint: Only one of those two will wind up reading a book written in their own language.

And that person will probably not be aware that you can charge more than a six-pack for the job. Sometimes it works out for the best, like for Dr. Frommer, who'd never created a language before Avatar, and yet did a spectacular job with Na'vi. Then again, he has a background in linguistics. You give the task to some random janitor or something and you might wind up with 700 words for "mop."

Creating A Language Is Full Of Hidden Pitfalls

"Perhaps the most challenging aspect of all is not letting your own native language -- in my case, English -- unconsciously influence the decisions you make about the language you're constructing," Dr. Frommer says. And not solely because English is a bastard language raised by 20 different abusive parents.

"Suppose you come up with a word for 'long,'" he explains. "Does it only refer to physical length, or can it be used for temporal length as well (as English does when we say 'a long time'? Maybe it doubles as the word for 'tall.' Those answers aren't obvious; you need to determine such things if people are going to use the language accurately."

That's why, in Na'vi, the word for physical length is "ngim," while "for a long time" is "txankrr." That's an important distinction, which also helps raise awareness of the horrific vowel shortage on Pandora.

In Avatar 2, the humans introduce the "I before E" rule and cause a decades-long global riot.

Say you want to convert "Stay away from that control panel!" to a new language. You come up with: "Blarg koy dor men kep ban!" It was easy -- you just replaced every English word with some gibberish. There's your first mistake: copying English syntax. (Now blarg in the corner and think about what you've done.)

"A new conlanger will do that sentence and believe that they now have a word that's equivalent to the English word 'control,' like in 'control your temper,'" Peterson explains. "They won't have considered that a different language might use a different lexeme entirely for the concept of maintaining one's emotions."

Meanwhile, the Dothraki control their emotions by holding both their tongue and others'.

"Inexperienced conlangers also reproduce irregularities of English, such as, for example, making the singular and plural forms of 'fish' identical-e.g. 'kam' = 'fish' (singular) and 'kam' = 'fish' (plural). In some languages there isn't even a word that means what 'tree' means in English; there are only words for specific trees (ash, oak, elm, pine, etc.)," Peterson says.

For example, in Na'vi there is no word for "waterfall" -- just five different words for falling and running water, because they have so much of that on Pandora. (And yet they don't have a word for "mind control.")

Don't go chasin' ... that.

A Well-Constructed Language Helps Tell The Story

"To create the phonetics and phonology of Na'vi, I included a group of sounds not often found in Western languages -- ejectives, which are popping-like sounds that I notated as kx, px, and tx," Dr. Frommer says. So the Na'vi word "ekxtxu" means "rough." To give you an idea of how to pronounce it, try to say "Eh, you" while simultaneously coughing.

It works in the context of the story. Na'vi is an alien language spoken by bipedal mammals (at least, we hope they're mammals, for Jake Sully's sake), so it should sound exotic but still be comprehensible to humans.

"The next step was to decide on the morphology and syntax," Dr. Frommer continues. "Since this was an alien language spoken on another world, I wanted to include unusual structures. So, for example, the verbal morphology in Na'vi is achieved exclusively through infixes, rather than prefixes and suffixes."

Infixes are relatively rare in human languages, but they do exist in, say, Nicaraguan Spanish, Tagalog ... and even English. Sort of. If you insert, say, "fucking" into the middle of a word, like in "in-fucking-credible" or "fan-fucking-tastic" then "fucking" will act as an infix that modifies the meaning of the word by adding emphasis to it. You see a similar though way more complex thing in Na'vi. For example: "Oe ka" means "I go" while "Oe kola" means "I went," or "I have gone," with "-ol-" being the infix indicating a completed action.

Sometimes. But notice nobody's in a hurry to correct the giant warlord Na'vi Predator.

But if your language is meant to just be future English, there's no reason for it to have nouns stuffed into verbs stuffed into adjectives like a linguistic turducken. "For example, the language I created for the Grounders in The 100 is just English 150 years in the future after a major societal collapse," Peterson explains. "That will be far different from an alien language." Just look at:

"Ai laik Okteivia kom Skaikru en ai gaf gouthru klir." Translation: "I am Octavia of the Sky People, and I seek safe passage."

Don't forget this similar phrase, for when it really starts to go downhill.

You can see some phonetic similarities -- even the syntax is shared between Trigedasleng (the name of the language) and modern English -- because the two are meant to be connected. This sounds like an insane amount of rules to remember. If you've already forgotten what "blarg" means, there's still hope: Even the best slip up now and again.

Even Language Creators Sometimes Forget Their Own Rules

Nobody is perfect, as demonstrated by every single decision Ned Stark makes in Game Of Thrones. This also applies to conlangers. They unintentionally break their own grammatical rules from time to time, because who can proofread for them? That's how errors sometimes creep into the final product.

You can cover them up as wacky comic relief with the right writer.

Peterson gives an example: "I forgot that I specifically designed the genitive/possessive case in Dothraki to make the nominative and genitive of the word 'khaleesi' identical, save in stress. Initially I was going to make a language-wide rule that two identical syllables be simplified to one, meaning the genitive of 'khaleesi' would first be 'khaleesisi,' but due to the rule about reduplicated syllables, the form would be 'khaleesi' with word-final stress. I thought it'd be a pretty cool way to make the word unique. Unfortunately, I forgot about that rule before it was too late. Thus the genitive is now the regular 'khaleesisi,' which sounds atrocious to my ear. It didn't really cause a problem (easier for language learners) -- just a bummer."

Don't feel bad: Even the Mother Of Dragons took several montages to get the language down pat.

That might seem like an insignificant mistake, but constructed languages feel so real because conlangers worry about little stuff like that. Nobody else will. At least until the internet gets hold of their work and never stops picking at it.

Constructing Languages Isn't Always Serious Business

On Game Of Thrones, the Dothraki are like a sexier Mongolian horde, while Valyria is more or less Atlantis with dragons. They are two proud and ancient cultures, and that's precisely what makes it so funny when you mess with them via language.

"The Dothraki word for 'eagle' is 'kolver,' which is based on Stephen Colbert's name," Peterson says. "If there is no connection between the world of the language and the real world, you can do things like have a word that looks (visually) like someone's name in the real world, as long as it's a licit form (i.e. phonologically, it's a pattern that works in the language)."

Fun fact: The Dothraki word for "I am currently choking on my own blood" sounds exactly like it does in English.

"Some words are even based on my wife's name," he says. Her name is Erin, so we get "erin," "erinak," and "erinat," which mean: "kind," "kind one," and "to be good." Aww, that's actually really sweet, but then again, knowing the Dothraki, how often do you think they actually use those words?

Even the Dothraki word for "friend" ("okeo") is based on the name of the Petersons' family cat. This type of tribute appears in Dr. Frommer's Na'vi as well: "The word for 'happy' is nitram, which is my brother's name spelled backwards," he explains. "It happens to fit into Na'vi phonology just fine."

But conlangers can't abuse their power like the mad, mad gods they are. Because ...

Conlangers Don't Own The Rights To Their Languages

"How does one own a language, given that languages are alive only so far as people use them?" Dr. Frommer asks. "Are Klingon and Na'vi and Dothraki speakers using a language owned by someone else, or do they in fact own it by virtue of their being the ones who use it for real communication? I'll leave it to the lawyers to try to figure that one out."

There's also the fact that constructing languages is always classified as work for hire, but Peterson points out that even if that wasn't the case, they couldn't own the rights to their work. "A conlang can't be copyrighted, and neither can a vocabulary; otherwise one could publish a dictionary, copyright all the words, and sue everyone who uses that language for royalties -- even if the language is English. A specific definition can be copyrighted (the wording used to define a term), but not the word or its meaning in the abstract sense."

"My second is legalese."

Of course, conlangers would love to receive royalties for their work, but it'd require a complete overhaul of our copyright system. So, in the meantime, they have to settle for making our fiction more engaging while immortalizing their loved ones in languages that thousands of people learn every day. That's almost as good as money.

David J. Peterson is a language creator and author. You can find him on Twitter, Tumblr, YouTube, and his website. Paul Frommer's blog on the Na'vi language is at naviteri.org. For elementary learning materials, see the fan-created site learnnavi.org. Contact Frommer at frommer@marshall.usc.edu. See also conlangingfilm.com for information on an upcoming feature-length documentary about constructed languages: Conlanging: The Art Of Crafting Tongues. Cezary Jan Strusiewicz is a Cracked columnist, interviewer, and editor. Contact him at c.j.strusiewicz@gmail.com or follow him on Twitter.

Have a story to share with Cracked? Email us here.

For more insider perspectives, check out 6 Bizarre Lies Hollywood Tells When They Base A Movie On You and 5 Things I Learned As A Child Star Of The Worst Movie Ever.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel, and check out Why Living In A Shakespeare Play Would Suck, and other videos you won't see on the site!

Also, follow us on Facebook, and we'll follow you everywhere.