5 Horrible Things I Found Out When I Made A Video Game

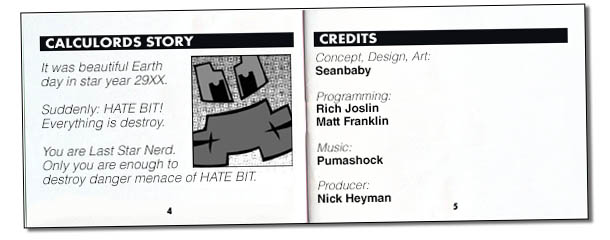

A few years ago, I fulfilled a childhood dream when I conceived, designed, wrote, and illustrated a video game called Calculords. It ended up being a weird, hard-to-explain game. In fact, describing Calculords is like explaining love to a robot: It's impossible, I do it all the time, and it always ends in sex.

Or you can just go play it; it's FREE.

In my game, you defeat space menaces with collectible cards which require you to solve number puzzles. I can say without ego that it's the deepest strategy game ever designed by a comedy writer, and two media outlets gave it Runner Up Mobile Game of the Year (losing both times to that stupid dick Super Smash Bros.). The number puzzles also made the game accidentally educational and, no bullshit, parents and teachers around the world use Calculords to trick children into learning math. You might ask me, "Does that make you a hero?" Well, I can answer that with two simple words: double yes.

The Industry Doesn't Really Encourage Innovation

When Calculords launched, the #1 game in the App Store was Flappy Bird. Flappy Bird was a clever mashup of bird poking and nothing, and it was making absurd money. Which is probably why someone made the second-most-downloaded game, Flying Miley -- Flappy Bird with a Miley Cyrus head. I'd say it's the kind of hilarious takedown of pop culture that comes along once in a lifetime, but the #3 game was Flappy Bird with a Drake head. My point is, if someone ever makes a successful video game, go ahead and make it again with a different name, and no one in the industry or the consumer market will fucking care. Hell, sometimes the ripoffs even do better than the original.

If you want, change a word or two. And feel free to add your favorite Marvel or Pixar characters. Seriously, no one gives a shit.

Most games, even amazing ones, are combinations of proven ideas. For instance, before they even started programming Final Fight, they knew their idea of "Double Dragon, only you're the mayor" was going to turn out so goddamn sweet. Right now, you can download a few assets and a game engine and release a competent ripoff game of your own in minutes. Make Candy Crush with Harambe and Ken Bone heads. Or wait, Candy Crush with differently colored candy! And along those same lines, did you know you can roll your neighbor's barbecue right out of their yard? And Ukrainian human traffickers buy children, even when they're uncooperative and not yours! There are literally thousands of ideas out there that can also be yours for free!

Think of designing a game like drawing a blueprint for a bicycle. It seems easy, since your brain assures you you know exactly what a bicycle should look like. Well, it turns out your brain was glossing over a lot of missing parts. Instead of a working bike, you draw an unspeakable contraption that could only be used to castrate steampunkers. That might be fun and useful, but it's not what you intended, and it's almost impossible to market. So you keep erasing, redrawing, learning new things, and inventing new parts until it's morphed into an awesome bike-like monstrosity that will change the way people shit their pants around bikes. By the way, while you were doing all that, everyone else just traced an old drawing of a bicycle on the way to the bike-making store. I don't know why I'm wrestling with this metaphor when one image can illustrate what I'm trying to say:

"Mobile games are your gateway to success!"

-- the 407th person to invent the Pet Rock.

In Calculords, my idea was to use math, the hated school subject, to send your armies into battle. At the time, there was no real way to know if that was fun or not, so I built a clutzy board game version to test it. This is called "paper prototyping," and it's like learning to kiss with a puppet -- anyone with magic inside them can do it, but it only kind of works. So I spent hundreds of hours drawing space monsters on blank cards while an objectively more successful game designer spent 40 seconds drawing Hulk Hogan's face on Flappy Bird and got his game approved by the App Store.

This seems like a nice time to remind everyone that when someone is willing to shit on their chosen industry for money, especially table scrap mobile game knockoff money, they are a greedy opportunist. And there's nothing wrong with that when you're being closely monitored in a heavily regulated setting. The mobile games marketplace is not that setting. Make no mistake: Anyone who rushed a cash-grab Flappy Bird clone to market has kept every wallet and groped every sleeping woman they've ever encountered. Or at least, they would have if they saw someone else think of it first.

Let me get back to actually talking about game design, which is something I truly love. After many, many tweaks, I was happy with the basic mechanics of Calculords, and we started programming it. My idea was coming to life, and math armies blew satisfying holes into each other. Then I realized the combat, which worked great when everyone was homemade paper cards, was way, way too slow for a video game. So I had to redesign the entire combat system. And when that turned out to be too complicated, I redesigned it again. So now I've designed the equivalent of four video games -- five if you count my idea to make Flappy Bird a pair of tits -- and I still don't have a single video game yet.

The more I think about it, the more I'm sure I would totally play Hulk Hogan Flappy Bird.

Also keep in mind that games look like absolute shit while they're being made. The interface was a scribbly wire frame, and every graphic was a placeholder; it looked like brave Clipart hot dogs slapping together in the silent void of space. At least 80 percent of it still only existed in the imagination, but the same could be said for my college roommate's relationship with a jar of peanut butter he labeled "Summer Glau," and those two made it. What I'm trying to say, unrelated to anything about video games, is don't eat peanut butter that says "Summer Glau." It absolutely does not mean it was once Summer Glau's peanut butter.

This smear of ugly is what the game looked like for the first couple months of prototyping.

I kept making adjustments on the seventh and then eighth redesign until I was confident Calculords would be a delight for the mind and fingers and we could really get started making it. Unfortunately, I then discovered ...

Surprise: Everything Takes 70 More Steps

By this point, I had written about 120 pages of documentation on the game, 100 were obsolete, and a lot of details still existed only in my head. So I had to start writing documentation on which documentation to ignore. I also had to start making cuts, because every tiny feature immediately became a labor of love.

Fun fact: This is most of a database entry for one Calculords card.

Say you have a space game and want to add customizable hats to each alien. What a fun, simple idea! First, you write a design bible so all the hats are consistent with the lore and animation. Then you write a technical doc for your programmers and artists, even if that's you. Now you're done, except you need to figure out how the actual player changes hats. It's either an all-new user interface or a massive change to an existing one, because no UI leaves room for a bunch of hat-changing buttons. Still, that's just a massive redesign and a whole bunch of hat art, right? Well, almost. What will you do to teach the player how to try on hats, or explain how trying on hats is even an option? A tutorial? Could you live with yourself if you wrote a trying-on-hats tutorial? I'd sooner write a tutorial on how to escape Phil Collins' mouth using only seven dicks.

Step one is a positive attitude. You've got to believe you can escape!

And I still haven't mentioned the obvious technical issues these hats might create. You're no longer dealing with 25 aliens who each need to run, shoot, fidget, and die. You're dealing with an infinite number of alien and hat combinations that need to be tested. Can you look a young dreamer in the eye and tell him his first job in video games is to spend all day trying on different hats, each sillier than the last? That type of thing is exactly how I ended up in Phil Collins' mouth!

Over time, all of these are solvable problems. But remember these hats are an unnecessary, pointless feature most players will ignore, and they've turned one week of your life into a prison of wacky alien fashion. And making games involves more than just "making the game." You may discover Apple won't accept your game because one of the hats has a confederate flag, and it can't be legally distributed overseas because cowboy hats are how Australians tell one another to fuck themselves.

Right in your face, Australian Classifications Board.

I illustrated Calculords with pixel art, mostly because my Nintendo Entertainment System was more influential than my art teachers, and I thought it gave the game a nice retro feeling. Then we decided to port it from iPhone to Android, and suddenly those countless, meticulously placed dots became my worst enemy. See, there's no standard Android device size-- you might have a tiny rectangular phone or a giant square tablet, and pixels don't stretch. So now I had to either stop sleeping and redraw my entire game or give players blurry, half-visible graphics. I chose the tedious, difficult option, because my Nintendo Entertainment System was more influential than my doctor.

No big deal, there are only about three quarters of a million pixels on most mobile screens.

The point I'm trying to make is that adding a feature to a video game is like adding a third person to your relationship, finding out one of them is a robot, then convincing both of them vaccinations are wrong. You'll encounter challenges you could have never expected, and others created by your own stupidity and lack of foresight. So if you've ever played a game that had anything "extra," like a multiplayer mode, or secret collectibles, or even the option to change the main character's name, take a moment to appreciate it. Whether it sucks or not, someone had to really want it there.

This is the Calculando 4000, one of many features I never got a chance to include in my game.

There's No "Good" Way To Make Money

You probably figured by the unmarketable, labor-intensive nature of Calculords that I didn't get into game design to get rich. I already have a great job where I write hilarity and a terrible one where I ask lost and founds if they found a bag of diamonds. So I made my game free.

Costing zero dollars isn't unusual for a mobile game. You may know all this, since it's both obvious and the plot of a South Park episode, but the mobile business model is to poke around in our brains' addiction centers until they strike oil. On a console, games cost the same for each person-- $60 and a touch of celibacy. Free games include bizarrely expensive content in the hopes of getting all their money from the one perfect addict. It's a lot like introducing yourself on Tinder with a picture of your perineum -- it devalues the very thing you're trying to sell and makes the world an uglier place, but like, it only has to work a couple of times, right?

The ethics of exploiting addiction get worse when you realize none of these microtransaction addicts can afford it. The millions of dollars Kim Kardashian makes from her phone game don't come from millionaires who also happen to be stupid fucks. They come from regular stupid fucks who shouldn't be buying virtual tit glitter. And some games don't even try for addiction. They are just hoping you're seven and know your parents' iTunes password.

Fun fact: The $99.99 option in Kim Kardashian's game is tapped exclusively by players having a seizure.

This is going to sound crazy, but I don't think you should do awful things that hurt people simply because it makes you money. So I set a limit on the things you can buy in my game. The world's most rabid, uncontrollable space card collector can't ever give Calculords more than $14, which is still a good deal for "easily the best collectible card game on iOS," but it led to some problems.

First, without stealing thousands of dollars from a few emotionally troubled users, the free video game business model doesn't make enough money to count as making money. Plus, when something has no cost, you're not motivated to get your money's worth. New games have learning processes, and if you invest zero dollars in one, you invest the same amount of time in figuring out how to play. I know how this sounds, but it's almost as if you have to tax the player in order to get them to learn how to play your game. Ugh. I type 15 jokes about Hitler a day, and that was the most awful sentence I've ever written.

So after a few months, we changed the price from zero to three dollars (then back to free again). And here's what's nuts: When it cost more money, more people downloaded it. And everyone who downloaded it played it more. They have a word for that kind of win/win situation in German: shitzenbergerslop. It literally means "to drop your pasta into an unflushed toilet," only filthier than that? It's really a beautiful language, but let's get back to what I was talking about.

Your Game Has Enemies

When you're making a game, you have no idea how to tune the difficulty. I've personally spent my life treating each video game like it's a covert Star League application, so my thumbs and brain are linked in ways only true, heartfelt lovers can understand. And in the process of designing, testing, and tweaking a game, it's hard not to become that game's greatest player of all time. So when I tried to zero in on the perfect challenge, I probably made my game too mean.

This turned out to be a bigger problem than you might expect.

The word "gamer" describes about 90 percent of the population at this point, but here's something all gamers have in common: They are, several times a week, the most important person in the galaxy. Each gamer is the only commander who can lead the Horde back through the Dark Portal, the only boy who can wield the Master Sword, or the only Bionic Commando who can save Super Joe. This gives some gamers a self-importance that borders on insanity. For instance, when someone who just this morning was the very Herald of Andraste dies in your game, that's not a "challenge." It's a conspiracy to steal your money. And nobody, nobody steals money from the Herald of Fucking Andraste.

Dozens of furious but awful gamers were certain our game's challenge was a "paywall." We were accused of this financial treachery despite our game being almost stupidly unable to take your money. A few declared it "pay to win" before it even launched. Despite that being absurd, it, like all crimes in the world of gaming, carried with it the penalty of SCORCHED GODDAMN EARTH.

Fun Fact: This email taught me that it takes three seconds to Google someone's name and ask their mother to be your Facebook friend.

Honestly, I'm complaining about a very minuscule group of people. Most people enjoyed the game and never called me a war criminal for including an option to pay money for it. Those who posted angry Facebook messages or incoherent zero-star reviews were few and far between. Still, it taught me that being a man making video games is like a woman doing anything -- you can give the world nothing but a free supply of objective awesomeness, and you'll still have crusaders hellbent on destroying you.

But not all your game's enemies are trying to destroy it because of crippling social disorders. Every user's finger is tapping in some sequence of madness your QA testing could have never predicted. Players will crash the game every way it can crash, or maybe they discover it won't start on an obscure model of tablet and act like you did it on purpose. Others might be confused by the the entirety of your game's concept and decide the world is better off without it. If you look at the reviews of Calculords, you'll see that most of them required two or three thousand words simply to explain what the hell it is, much less how to play it. Which leads me to my next point: It is impossible to predict the capabilities of your game's hypothetical players.

Almost to a fault, I assume everyone around me is capable and smart. This means I spend a lot of my time being unpleasantly surprised, but that's what all these jokes are for. You can't have that kind of attitude when you're making a game. You have to assume each player is a disoriented Beothuk tribesman who crawled out of a recently unfrozen glacier. You have to treat them like they've never seen a controller and the word "button" contains three shapes forbidden by their ancient gods.

Above: The entirety of Calculords' instruction manual.

So in order to accommodate users far beneath my expectations, I had to create the thing I hate most: a tutorial. Let's be clear, I've hated every tutorial I've ever been forced to sit through. I don't know where someone gets the balls to make a 176th barely different version of Final Fantasy or Call Of Duty and then assume I'm the idiot who needs help deciphering a joystick. Still, Calculords was a bizarre thing no one had ever seen, and I figured a bit of instruction was better than baffling mystery.

So I made a tutorial. It explained everything, and it was seven motherfucking lifetimes long. The simple act of showing players how to play my game ruined my game. I cut it down, then again, then again, and kept trimming until I barely explained 10 percent of the features. I live by few rules, and one of them is that I'm not going to mansplain space murder to you. As it turns out, my rule goes against all design philosophy for a reason. I heard from legitimately intelligent, clever people that they got confused and gave up early. Still, I fight the urge every day to go in and trim out more of that soul-sucking tutorial. I truly believe a tutorial should never be more than you asking your friend not to kick you for a second while you figure out your buttons.

There's A Covert Industry That Exists Only To Leech Money

Days after our game launched, I started getting emails every few minutes from marketing experts who wanted to promote Calculords. They each spoke in a paradigm-shifting, SEO-optimized corporate language, as if someone put a sack of diarrhea into Google translate.

Marketing is far outside my skill sets and areas of interest. If you've followed my career, you probably know my brand of self-promotion is quietly posting an article, then leaving the internet alone until the next one is done. It's a system that works for me, since anyone looking for hilarity can easily find them. But only a lunatic would search for a space card game about math, so I figured I should hire one of these PR reps if I wanted anyone to hear about Calculords.

I set up calls with several companies, and I knew 30 seconds into the first one that I'd made a terrible mistake. Mobile game promotion has all the precision of discount cluster mines, but with none of the respect for human life. It's not like making a compelling advertisement and hoping people click on something. Mobile game promotion is more like peeing all over everything until the world can't get rid of your smell. Let me explain.

Mobile games don't get a huge amount of support from the enthusiast press. In fact, many mobile game review sites do the exact opposite. We were contacted by several sites and magazines which wanted to review our game in exchange for money. If I was okay with those ethics, I'd still be selling "LIRV STRONG" bracelets to well-meaning illiterates.

The majority of mobile gamers don't read press reviews. The entirety of their research is done by opening their phone and browsing the best-selling games. Obviously, that means the best-selling games sell more games, which makes them better-selling games, which makes them sell more games. So marketers aren't trying to get your game press. They're trying to get your game downloaded. You might be saying, "Wait, isn't getting your game downloaded, like, the endgame, not the first step? That sounds suspicious?" You're right.

There are companies -- lots of them -- which use every possible dirty trick to get your game downloaded. For example, they can attach your app to a coupon that only works after you've downloaded the game and had it open for 30 seconds. Or maybe they hire all of Bangladesh to download your game over and over and over. They will push your app to the top of the charts while global warming pulls their country into the ocean! We win again, underprivileged!

Some companies specialize in getting your players to stop playing and sign up for subscriptions or take surveys or submit credit reports. I sat through pitches for dozens of mobile marketing schemes, all of which seemed designed entirely around convincing people video games are evil. None of them were for me. If you're the type of person who fills out 20 minutes' worth of credit report for 7 cents worth of a Starbucks card, my game and all future games I make are too hard for you.

I can barely keep all these these shapes and numbers straight myself, and I invented them.

I didn't get into making interactive fun to trick the poor and confused into downloading my video game against their will. If all I wanted was to make a giant mess so I could exploit it for money, I would have poisoned a reservoir and started a bottled water and coffin business. If I wanted to get paid for adding nothing of value to the world, I would scream wishes into jars and sell them to Bjork. I guess what I'm starting to realize is that all my backup business plans are terrifying and insane. So for everyone's safety, please read my free jokes and play my free video games generously.

Experience a day in the life of a couple of highly successful video game scribes in 6 Things You Learn Writing Blockbuster Video Games, and find out what happens when the video game industry blows up in your face in 5 Things I Learned as the Internet's Most Hated Person.

Subscribe to our YouTube channel, and try to wrap your head around this nonsense in 7 Video Game Puzzles That Made No !@$&ing Sense, and watch other videos you won't see on the site!

Also follow us on Facebook, because we're awesome, and you deserve it.