5 Tricks That Finally Got the Authorities to Come Down and Fix Stuff

Owen Wilson and Wes Anderson were roommates in college, and they tell a story about how their old landlord refused to fix the broken windows. So, the two came up with a plan to stage a break-in, which they figured would force the guy to act.

Exactly what this deception entailed, they don’t say. They also claim they later ended up slipping away from their apartment in the middle of the night, which made the landlord sic a private investigator on them, making it sound like the plan contained some flaws, if the story’s even true.

Don't Miss

When you need something fixed, you need to get more creative than that. For example…

A D.C. Guy Brought Giant Rats to the Rich Neighborhood

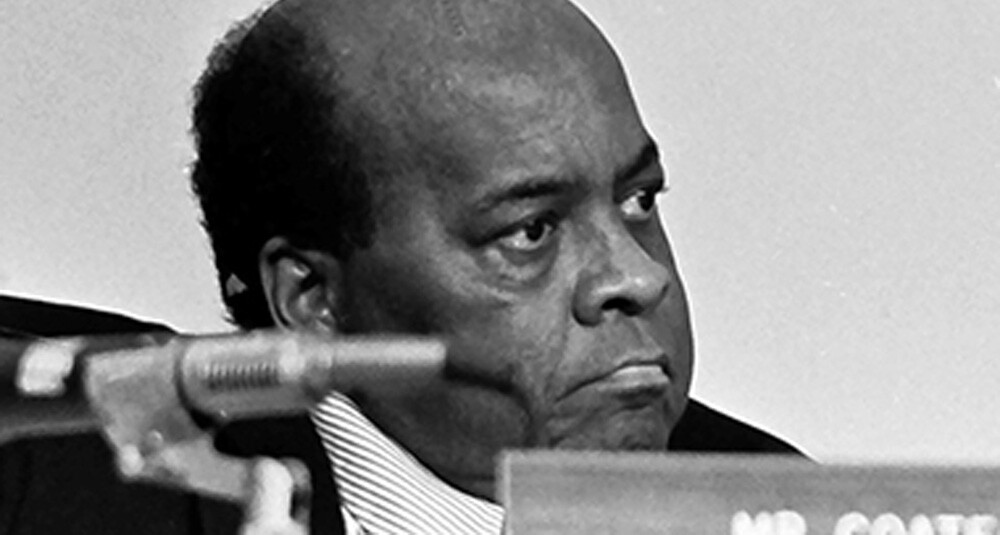

In 1964, there was a rat problem in Washington, D.C. Specifically, there was a rat problem in some parts of Washington, D.C. Rats swarmed in the northeast and southeast corners of town, but the richer necks of the city remained untouched, and therefore, didn’t consider this a problem worth addressing. Julius Hobson lived in the northeast, and while he’d join the city council after another decade and get some power, for now, he needed to try something on his own.

He took to catching the largest rats he could find, putting them in a cage and strapping it to the roof of his car. He’d then drive into Georgetown — the area that housed both the rich and the city’s politicians — and threatened to set his rats loose. You might figure it would be illegal to release vermin in such a directed manner, but it was not. No one had ever tried doing it before, so no one had ever passed a law against it.

In time, the tales around Hobson grew as large as the rats he was threatening to let free. He owned a farm and was breeding rats, people said. He was running an entire caravan of cages strapped together, with rodents about to escape. He’d released hundreds of rats already and was planning on releasing more. Either way, the city gave in and now funded exterminators to deal with the problem.

Ironically, Hobson was secretly a rat himself. He was a confidential informant being paid by the FBI. Some theorize, though, that he was secretly feeding the FBI false info to confuse them. A good trickster keeps everyone guessing.

Scientists Opened a Restaurant Full of Poison, to Get Food Regulations Passed

The 19th century was a fine time to sell food. Let’s say you sold peas, and they were gross and brown because you stored them in a ditch. You could make them look green by adding in some copper sulfate. This additive would damage people’s livers and brains, but no one knew that, and even if they did, there were no laws keeping you from using the stuff or disclosing that you used it.

When the next century rolled in, Harvey Wiley in the Agriculture Department wanted the government to start regulating food. Simply proposing they do so wouldn’t work. Instead, he ran an experiment, which consisted of a restaurant where diners ate increasing amounts of these additives. He suspected, correctly, that many of these chemicals were poison. The restaurant’s volunteer test subjects became known as the Poison Squad.

They ate food with copper sulfate, food with sulfuric acid and a whole lot of food with borax. When they signed up, these 12 volunteers assumed the risk of death and waived all right to sue if the poison made their eyes pop out.

Wiley submitted his results to the government, who didn’t do much with it because the Agriculture Department’s job is to protect industry, not protect health. But when newspapers got their hands on the results, anger spread, and the government really did end up passing the first food regulations. Wiley then went on to a more satisfying job than working for the government: He ran the lab over at Good Housekeeping.

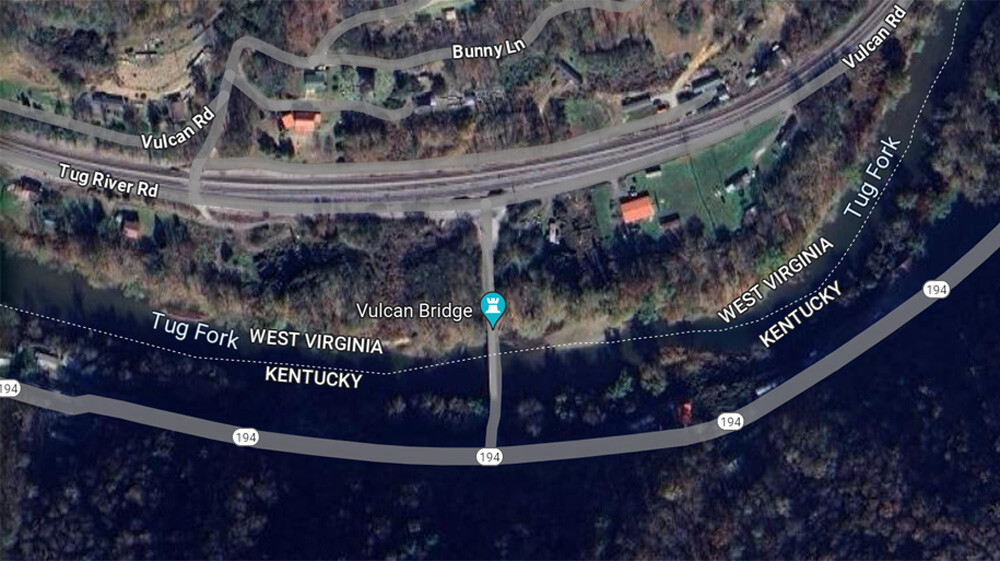

West Virginia Appealed for Help From the Soviet Union

For years, the only entrance into Vulcan, West Virginia, was by crossing the river over a tiny bridge. A coal company built it for miners to cross on foot; then, when cars became a thing, the people of Vulcan reinforced the bridge as best as they could. That didn’t work forever, though. In July 1975, the bridge collapsed. The town became pretty much cut off from the world.

Someone had to take lead on solving the issue, and that someone was John Robinette, a carnival barker. We’re not mocking him — he was literally a carnival barker, when he wasn’t working as a bartender. Robinette declared himself mayor, and no one could stop him because Vulcan was an unincorporated community with no preexisting government. He now appealed to the state for funds for a new bridge. They turned him down.

After two years of failure, he appealed next to a higher authority. No, not the federal government. He sought international aid. And he didn’t write to some wealthy nation for support. He wrote to East Germany and the Soviet Union, two countries delighted to learn the mighty United States struggles with caring for its citizens. A Russian journalist living in New York now came to Vulcan to tour it. Appalachia was indeed an unusually poor sector of the U.S., and during this era, even American journalists would often report on it as though having traveled to a foreign country.

This journalist, Iona Andronov, promised that Russia would rebuild the bridge if the United States could not. Such humiliation could not stand, so West Virginia now ponied up the million-plus dollars necessary for a new bridge, which still stands today.

One Town Decided They Were Fine With No Approval

In the 1860s, a new community in Texas found themselves petitioning the higher government, and they didn’t want money. They just wanted a name. Or better put, they wanted their own post office, and for that, the postal service needed to recognize them under a name that's official. Six times, the town submitted names (none of which have been recorded for posterity). Six times, USPS rejected them.

“Let the post office be Nameless and be damned!” the town finally wrote back.

The postal service accepted this suggestion, and the town became permanently known by its new name: Nameless.

Wanksy, Drawer of Dicks

Cities don’t always respond to maintenance issues. They do respond to vandalism, so in 2015, one British crusader figured out how to get officials to respond to potholes: He drew penises around them.

He signed the art “Wanksy,” naming himself after another artist with less talent but more fame. City councilors were outraged. “Has this person, for just one second,” one asked, “considered how families with young children must feel when they are confronted with these obscene symbols as they walk to school?”

This quote sounds like it was purposely designed to set up a comeback about how such families feel regarding road safety, but no, this was the council’s genuine statement on the matter.

“It’s also counterproductive,” read the same statement. “Every penny that we have to spend cleaning off this graffiti is a penny less that we have to spend on actually repairing the potholes!”

This was false. That’s not how maintenance works, and in fact potholes that had lingered for eight months were now suddenly filled within 48 hours. Some workers appeared to have their priorities especially straight, though: They concentrated on filling the holes without bothering to fully remove the art.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.