5 Experiments That Proved the Exact Opposite of What They Wanted

Did you know that visitors to this site are statistically likely to be sexier than people in general? At least, that’s the hypothesis behind the new study we’re doing. And if the study reveals anything other than that, you can trust we’ll never share the results with anyone.

Sometimes, a study doesn’t prove what it sets out to. The result is an embarrassment for everyone involved, such as what happened with...

The Wallet Experiment

You find a wallet someone dropped. Do you seek to return it, or do you keep the cash and toss the rest? A few different experiments have placed wallets in different cities, to try to compare honesty across cultures. Reader’s Digest tried this, and they concluded Helsinki and Mumbai are the world’s most honest cities, while Lisbon and Madrid are the least honest. However, they only dropped 12 wallets in each city, so this study doesn’t prove much of anything. Maybe 11 out of 12 wallets were returned in Finland, but maybe only three would have been had different people there stumbled on them.

Don't Miss

The University of Michigan tried the same thing with a little more rigor. They dropped far more wallets: 17,303 in 40 countries. Rather than drop them in the street, they pretended to have found them and handed each in at places like movie theaters and offices. They arranged it so the employees who received the wallets likely were not being monitored so were able to either keep the wallet or use the email address inside to pursue the owner. Each wallet contained a shopping list and business cards in the local language, and some contained a house key.

Some wallets contained cash, while others did not. Researchers predicted that people would more likely return wallets that held no money. The researchers also held surveys before the experiment, asking either the general population or hundreds of economists, and all agreed that the cashless wallets would more likely be returned. The reason, very simply, was that when a wallet contains money, finders would like to keep that money.

The experiment ended up offering all kinds of data about how people vary in honesty, but it showed one consistent trend everywhere: People were always more likely to return a wallet that held money. Researchers did a follow-up comparing wallets with a little cash against wallets with more cash, and the wallets with lots of money were more likely to be returned. One possible explanation, that people hoped for a larger reward from the money wallets, did not hold water. Instead, the researchers plotted the results like this:

Besides desire for money, the researchers discovered subjects were driven by such motivations as “altruism” and what the paper called “aversion to viewing oneself as a thief.” You might instead call that second part “morality.” Discarding someone’s shopping list and business cards would be inconsiderate, but pocketing their money would be wrong. Some people do in fact care about that, to the surprise of hundreds of economists.

The Attempt to Make Cuddlier Hamsters

We have a new technique for editing genomes, and it might be the greatest medical innovation since flavored opium. It’s called CRISPR-Cas9 editing (you might hear it just called “CRISPR”), and in theory, we can use it to scratch away people’s various genetic diseases. Plenty of challenges, however, stand in the way of our quest to change people at will. For starters, genes don’t always do what we think they do.

In 2022, scientists used CRISPR tech to totally remove a type of receptor from the brains of hamsters. These receptors are called Avpr1as, and they respond to a chemical called arginine-vasopressin, which makes males aggressive. By removing the receptors, the scientists figured we’d render the males passive and cuddly. But when they tried it, well...

…the male hamsters instead became much more aggressive and attacked each other. Whoops. We’d contact the scientists to ask how they feel about this unexpected development, but we need to accept the possibility they’ve all been killed and eaten.

The German Census of Jewish Shirkers

In 1916, Prussian War Minister Adolf von Hohenborn decided now was a good time for the army to hold a Jew Census. You might think the army had its hands full at that point, thanks to the whole “war” thing going on, but von Hohenborn came up with this Judenzählung to determine exactly what the Jews were doing in the army. Were they perhaps all grabbing the easiest and safest roles possible?

No, it turned out. In realty, 80 percent of Jewish soldiers had been serving right on the front lines, which explained why so many thousands of them had died in combat.

So, the government had expected to find evidence of Jewish soldiers shirking duty, but they found the opposite. The irony ran deeper than this, though. The government didn’t publicly state that they wanted to discredit the Jews. They publicly stated that this census aimed to fight anti-Semitism, by debunking conspiracy theories about what Jewish soldiers were doing. They privately wanted the census to support those theories — they wanted it to reveal the opposite of the stated goal.

Instead, the census really did debunk those theories, the way the government claimed they wanted but really did not. So, authorities responded by refusing to release the results. This was to “spare Jewish feelings,” claimed the government.

Zeeman and His Math Sphere

A sphere is a ball that exists in three-dimensional space. Mathematicians also call that a two-sphere, distinguishing it from a one-sphere, which is a 2-D circle. A three-sphere would be a ball in four-dimensional space, while a four-sphere would be the boundary of a ball in five-dimensional space.

Let’s imagine a rope in five-dimensional space. Its ends are linked up, so the whole thing is one big loop. Suppose this rope is knotted. Could you undo that knot, on this rope on a four-sphere, by passing the rope through itself? You can’t on a two-sphere, but you could on a three-sphere, so what about a four-sphere?

If that last paragraph sounds completely unintelligible to you, don’t blame yourself. Mathematician Erik Christopher Zeeman might have been the world’s expert in the mathematics of knots, and he spent seven years working that problem, trying to find proof that says a knot like that can’t be untied. This is complicated stuff.

Then, one day, he tried proving that such a knot can be untied. He managed that in a couple hours.

The Flat Earthers’ $20,000 Gyroscope Investigation

Speaking of dimensional spheres, if you’re seeking evidence that the world is round, you’ll manage that easily. Just watch the sunrise over the horizon, and boom, you’ve seen the curvature of the Earth. Go out in a boat if you can, or go someplace rural where fields stretch out to the horizon, or go up in a tall building. If you’re seeking evidence that the world is flat, however, well, that’s a bit tougher.

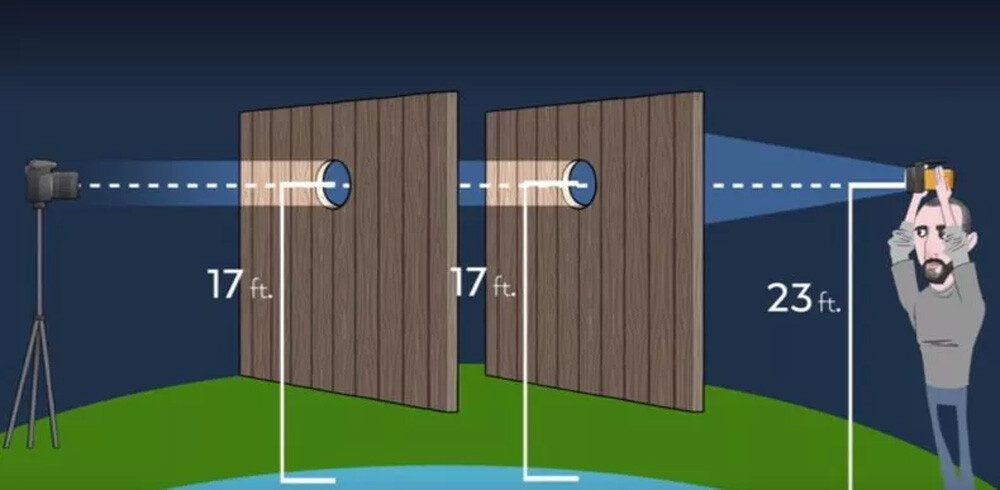

In a 2018 documentary, a group of courageous Flat Earthers set up an experiment. They erected a series of tall walls, some distance apart, each with a hole at the same height. They shone a beam of light through one hole toward the other. Light travels straight. So, that ray should have gone through the second hole as well, given that the Earth is flat. Sadly, the light instead hit above the second wall’s hole, a discrepancy that would instead suggest the Earth is round.

Delta-V Productions

A second experiment used more advanced technology. Host Bob Knodel brought out a $20,000 laser gyroscope, which should keep to the same vertical orientation no matter what goes on with the ground beneath it. As time went by, a problem revealed itself here. The gyroscope “drifted” by 15 degrees every hour. That’s equivalent to doing a full rotation every day with respect to the ground, as though the Earth itself is rotating constantly. “We obviously were not willing to accept that,” said Knodel, and he persevered onward.

Troublesome data must be rejected. When experiments challenge your world view, you must switch to a different experiment you can trust.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.