5 Shopping Tricks Stores Had to Shove Down Consumers’ Throats

It’s the most wonderful time of the year for shopkeepers looking to unload their stock on the public. Holiday shopping is an annual tradition and a routine that many of us have been experiencing our whole lives. The basic mechanics of shopping, meanwhile, are even more routine and feel like a fundamental part of life as a human being.

Don’t take this ritual for granted, though. Various individual aspects of shopping were once new and strange. Customers outright rejected them, until retailers got smart and figured out how to sell us on how they sell to us.

Customers Considered Shopping Carts Insults

Don't Miss

Today, when you go to a supermarket, you choose between a shopping cart or little shopping basket, depending on what kind of damage you plan on doing. At the start of the 1930s, your only option was the basket, which naturally limited how much you could buy during a visit. Then supermarket owner Sylvan Goldman came up with an idea. He linked two baskets together, on a wheeled metal frame. This way, each shopper could buy twice as much in a single trip.

The shopping cart would evolve in the years to come. The biggest improvement for stores was when carts became telescopic, meaning one empty cart could slide neatly into another for compact storage. Another brilliant improvement allowed you to lift and lock the lower basket for easy unloading. This was eventually made impractical by a further improvement, which eliminated the multiple baskets in favor of one huge cart, so customers could transport even more with each trip.

But these customers initially rejected Goldman’s invention. For starters, carts came off as a naked attempt to make shoppers buy more, and customers are occasionally savvy about that sort of targeting. That’s if they could even afford to buy more (the 1930s were famously not a good time, financially speaking). The idea of pushing an entire vehicle of goods around, like a wheelbarrow, also sounded absurd. Women said it reminded them of pushing strollers, which was not something they wanted to the be thinking about. As for men, they resented the implication that they were too weak to carry all their shopping in their own hands.

Goldman won over his customers by paying stooges to pose as shoppers who pushed carts. Legit customers followed the stooges’ example, and the trend spread from there. Goldman became fabulously wealthy licensing his invention, and when he died, he left around half a billion dollars to his two sons. That should have set both those boys up for a life of happiness. Except, they both ended up shooting themselves to death.

Yeah, sorry about dropping that on you, but in 1995, Monte Goldman shot himself and died. Two years later, his brother Alfred shot himself and died. Side note: An urban legend says Christmas is the most common time of the year for suicides. That’s untrue. It is actually the least common time of the year for suicides. So cheer up!

Escalators Were Fearsome Adventures

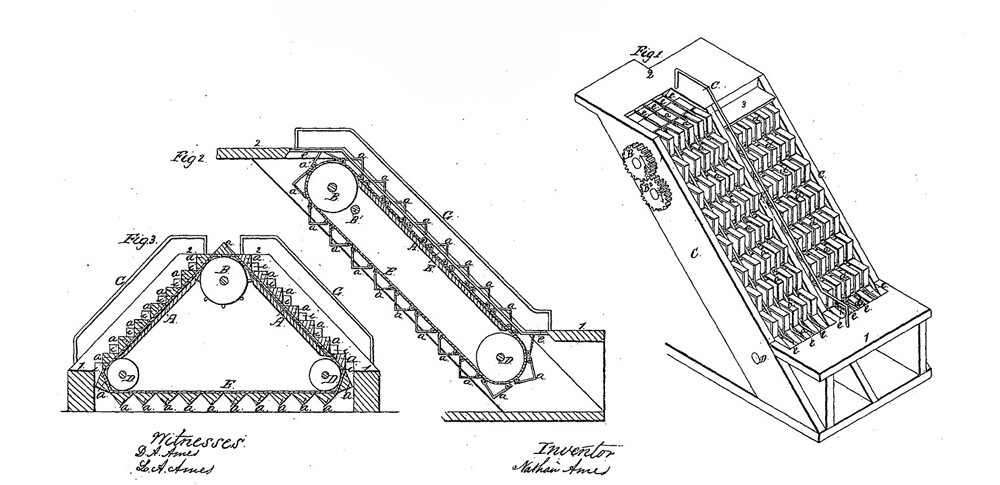

Many people conceived of the idea of an escalator before anyone managed to physically build one. People were probably imagining escalators around the time of the very first staircase, if not sooner. A patent for an escalator went to a Massachusetts man, Nathan Ames, in 1859. This guy never managed a prototype of his “revolving stairs,” and his other planned inventions included a copying machine (you wrote with one pen, and wires operated a second pen) and an improved cheese grater.

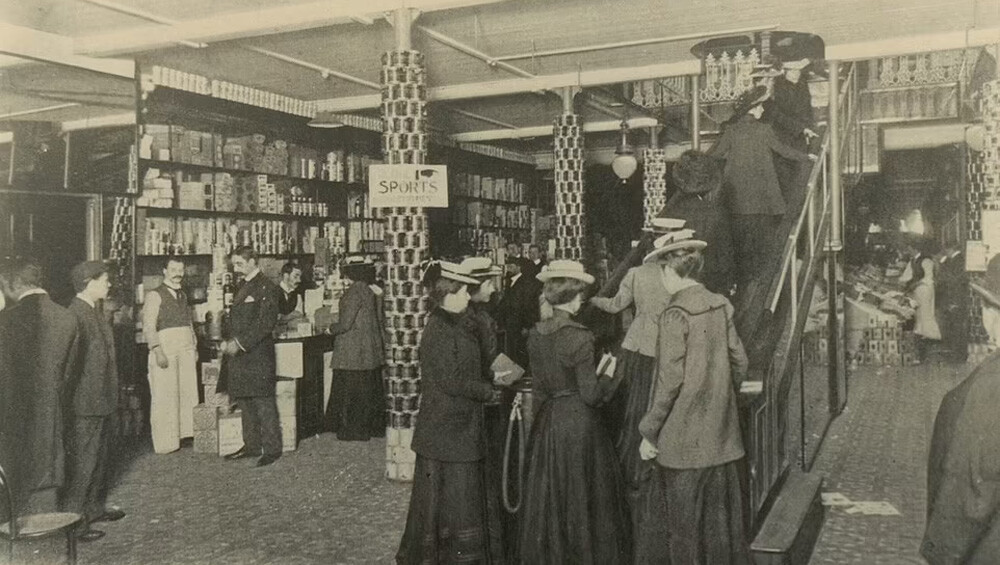

No one built an escalator for almost 40 more years. Then Harrods in London installed what they called a “moving staircase.” The name was misleading because it had no stairs. Today’s escalators are closer to Ames’ invention, while this first functional escalator was a single leather belt that rose at a slow incline.

Brightman Images

Lifts had existed prior to this, but lifts were terrible bottlenecks. The moving staircase offered obvious advantages. “As far as the shops are concerned,” wrote one publication, “it seems as though it would solve the difficulty of getting people to do their shopping higher than the first floor.” Of course, a flimsy leather belt did not inspire much confidence from the first customers who had to brave it. To treat customers’ varying levels of distress, Harrods stationed a butler at the top. To the women, he offered smelling salts. To the men, he offered a swig of brandy.

Brightman Images

Other sources describe customers’ reactions a little differently, saying the smelling salts were for ladies “overcome with joy.” That sounds awfully like a 19th-century way of implying this escalator gave women orgasms. We question this claim. We see many people have orgasms on escalators, but it’s usually men, and it says less about the escalator than it does about the sort of clientele who patronize the subway.

Credit Card Companies Needed to Mass Drop Cards on People

Credit is another concept that was conceived of long before it was perfected. People were exchanging goods on credit long before we’d even formally invented the concept of money. Credit cards, however were a harder tech to establish. And we’re not just talking about how the tech in cards has evolved, from magnetic stripes to chips to the marvels of casual tapping.

Credit card companies first faced a catch-22. They could explain to customers all the benefits of getting goods now without having to pay for them (not having to pay until later, at least, and who cares about later). But customers still reasonably refused to sign up because stores currently did not accept credit cards. And companies could explain to stores how cards would encourage customers to buy more, would speed up checkout and would reduce how much cash employees stole (and all it would cost the store is a significant percentage of every single transaction). Stores still reasonably refused to honor credit cards because no customers had credit cards, so what would be the point?

By the 1950s, plenty of stores offered their own credit cards, and plenty of customers used these cards. This process worked easily. The store would say, “Hey, you shop here a lot, want this credit card with us?” and the customer would say, “Sure, as I know you’ll honor it, since you’re the one issuing it.” Banks, however, wanted to issue all-purpose credit cards, which shoppers could use everywhere, and no one seemed interested, for the reasons we just listed.

The answer came from Bank of America’s Joseph P. Williams. He just mailed credit cards, unsolicited, to everyone in Fresno who had a Bank of America account. You know “pre-approved credit card” offers, which some see as predatory? This was one step further than that. Instantly, 65,000 people had credit cards in their hands, cards attached to no store in particular. Suddenly, stores had reasons for accepting these cards.

The experiment was not a total success, however, and it got even worse when Williams expanded it to Los Angeles. Lots of people who received cards simply used them and never paid them down. Bank of America could not legally just debit the money from the associated accounts, and they hadn’t created a collections department for pursuing these debts. Around a quarter of all the bank accounts that received active credit cards were delinquent anyway. Other people received duplicate cards, or other people’s cards, or stole each other’s cards and used them with impunity.

The pilot program lost Bank of America over $200 million, in today’s money. Still, it paved the way for the wide adoption of credit cards, a system that — once the credit card companies figured out how to properly police it — we can all agree led to no further problems whatsoever.

Picking Out Goods Yourself Seemed Like Too Much Work

So far, every shopping situation we’ve described has involved shoppers going into stores and loading up on goods before heading toward the checkout. This is not a universal idea, and until 1916, it didn’t exist at all. Back then, you would go to a store and tell the clerk what you wanted, and he’d fetch it for you. The stuff didn’t lie within your reach, and you didn’t collect the items yourself, for the simple reason that the goods belonged to the store, and you hadn’t paid yet. The products went into your hands after you paid for them, obviously.

The first store where customers collected goods themselves before paying was Memphis’ Piggly Wiggly. The name sounded strange to people at the time, but rhyming would soon become standard; our friend Sylvan Goldman would go on to buy another grocery chain called Humpty-Dumpty.

The new Piggly-Wiggly system took people by surprise. People now had to fetch goods off shelves, doing the work of a shop clerk. Piggly had to lure customers in to this weird store where they’d do unpaid labor, by saying the store was holding a beauty contest. The judges (actually reporters, who weren’t judging anything) handed prizes to every single woman who entered, until the prizes ran out. Though a sham, this was no more ridiculous than any other beauty contest, and the prizes were substantial — gold coins, worth $150 or $300 each in today’s money.

Every customer who entered the store discovered this new grocery store system, known as “self-service,” turned out to have a lot of advantages. Because the place didn’t have to employ so many clerks as competitors did, they offered just about everything more cheaply. Plus, people preferred leisurely browsing goods and picking out whatever they liked rather than reciting their prepared list to a waiting employee (or handing over a written list, which was the other default way stores worked at the time).

The shift, in many ways, mirrored the eventual introduction of self-checkout lanes. In fact, if you use the term “self-service stores” today, everyone will assume you’re talking about self-checkout, rather than this system of shopping that no longer needs its own name.

Online Shopping Didn’t Work So Great When Home Internet Sucked

To some of you, all these descriptions of stores are equally alien. You instead shop online, with the very device you’re using to read this. Obviously, shopping online is convenient. For example, when you shop online, you don’t have to have sex in the changing rooms — you can have sex in your own bed because you’re already home. Yet, online shopping offered a few hurdles before customers adopted it.

Amazon

Consider how online stores tried to adapt Black Friday for the web. Black Friday has been a thing since at least the 1950s. Once online shopping began, retailers extended Black Friday discounts to online purchases as well. However, not too many people made use of them. Instead, stores saw a rush in online orders the following Monday. People waited till they were in the office because that’s where they had internet access — or, for the many people who had the web at home, the office was where they had fast internet access.

Eventually, home internet would speed up. Today, people do indeed shop for Black Friday deals online from home. But retailers weren’t going to wait for the world to evolve. They leaned in to the schedules people set for themselves, and starting in 2005, retailers declared the Monday after Thanksgiving to be Cyber Monday. Cyber Monday remains an institution today, even when there’s no longer any reason to schedule these sales for Monday, rather than the previous Sunday or Saturday. Who knows how much productivity we lose thanks to office workers browsing deals on Cyber Monday instead of doing work?

Yes, Cyber Monday remains an institution — and also remains one of the few examples of us still using the word “cyber” when talking about the internet. For a few years, “cyber” referred to cybersex, and today, it doesn’t even mean that. We’re just left with Cyber Monday. Or cyberpunk. Or cyberterrorism. Choose wisely.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.