5 Costly Monstrosities We Built and Never Used

Money is a funny thing. It rarely ever goes away. It you spend $2,000 on a giant sack of deer shit, and you have absolutely no use for deer shit, the money isn’t lost. It went to someone, who came away thinking this was an awesome deal for them.

The entire construction industry may work this way, with people getting rich off projects regardless of whether the resulting structures serve any purpose. Still, you tend to hope that such structures do get used. The following ones didn’t.

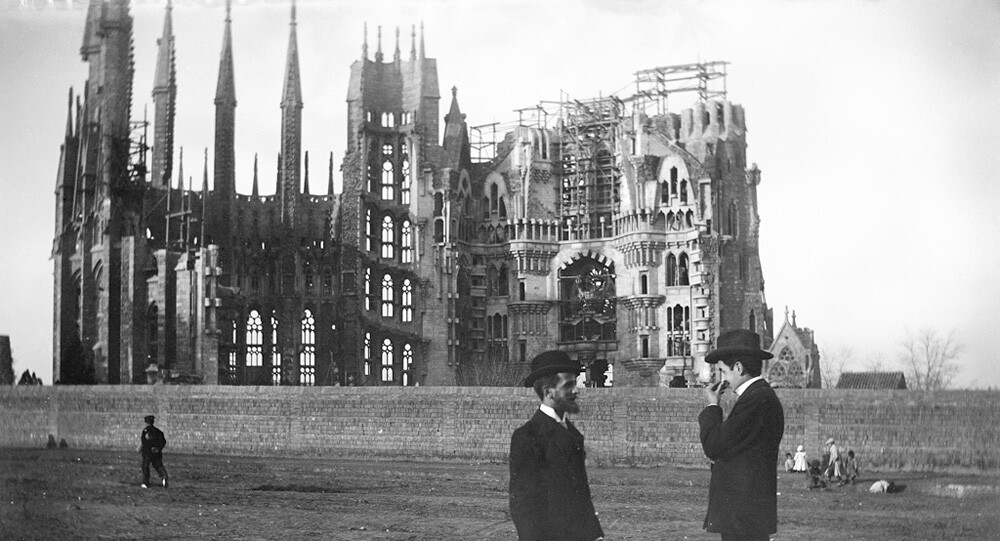

The Church Still Under Construction After 140 Years

Don't Miss

In the 19th century, a Spaniard named José María Bocabella decided to build a church in Barcelona. He wanted to model it after a shrine he’d seen in Italy, one with all kinds of history (angels lifted it up during the Crusades, according to legend) but which looked fairly reasonably easy to replicate. Within a year of construction, the architect quit, and the new one brought a new plan. The new Sagrada Família church would be gothic and fancy and huge. “My client is not in a hurry,” said the architect, referring not to Bocabella but to God. He died in 1926 (the architect, not God), run over by a tram. The church was at this point a quarter complete (at most) after almost 50 years of work.

“Or to not make it, whatever.”

More complications delayed construction as the decades passed. In the 1930s, Spain had a bit of a civil war that killed half a million people. Most of the city’s churches were burned, with most of the priests and nuns murdered or displayed dead in public. The only reason no one burned down Sagrada Família was there wasn’t enough finished to destroy. Revolutionaries did burn the crypt and destroyed the construction plans they found of the church. It took another 16 years to piece those plans together and figure out what to do next.

Construction crawled forward throughout the rest of the 20th century. When the 21st century got going, planners set a new target. They’d open the church in 2026, the centennial of the architect’s death. That sounds like a joke, targeting 100 years after the architect died, and it was a target they realized they couldn’t meet, thanks to a new issue that eventually popped up: COVID. Yes, they had to stop in 2020 — which might seem like just one hiccup out of many in this church’s long history, but this was in fact the first total halt in construction since that civil war almost a century earlier.

When will the church be done? “It could be in 2030, 2035, 2040,” said the director general. Still, you’re welcome to visit the incomplete building. You can even attend church services there. You can also attend church services outdoors. God is everywhere and has no special love of towers; this is the message of the first book of the Bible.

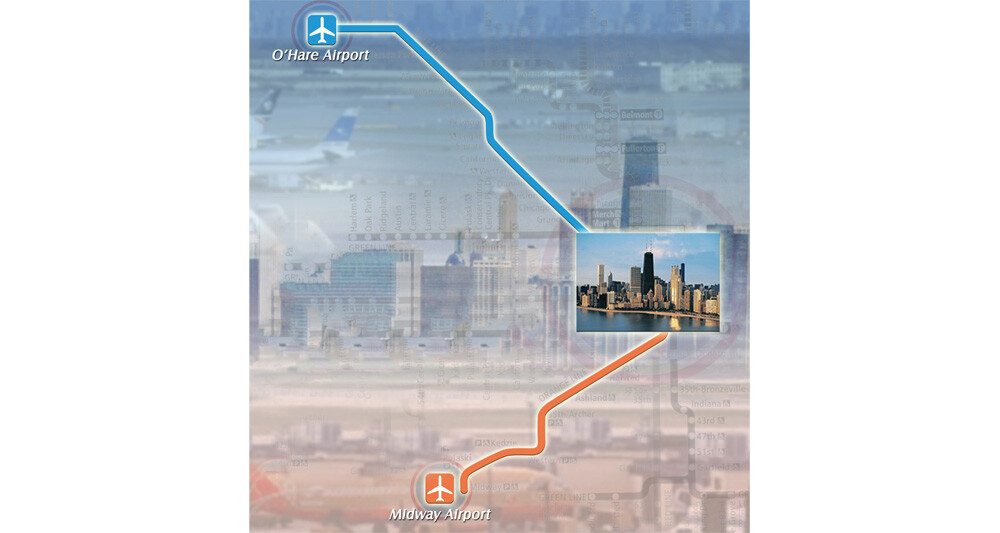

Chicago’s $400 Million Abandoned Subway Station

If you’re in Chicago and want to take public transport to the airport, you could take the L to the Washington Library then walk to Jackson and switch to the Blue Line and fall asleep, then discover service is down between Logan and Belmont, forcing you to get down and find a shuttle bus. Instead, what if the city had a superstation, which shot nonstop trains to each of the city’s two airports?

Chicago Transit Authority

Of course, you’d still need to get to the superstation, which will require a whole bunch of additional infrastructure. Surely you realized that, after a few milliseconds of thinking. Chicago apparently did not. They sank $400 million into constructing their superstation before calculating that all the additional ancillary construction would cost another billion or more. They figured this plan was worth a crazy amount of money but not a stupid crazy amount of money, so they gave up on attaching any way to access this station. That was after they’d built this station that will never open, and people in Chicago are still paying for it.

Such ventures aren’t unheard of in the world of the underground. For example, have you heard of the Cincinnati Subway? Maybe not, since the city doesn’t have an active subway system (its “metro system” consists entirely of buses). Still, they did start building a subway back in the 1910s. They needed to build one since the city was relying on streetcars, and even at the time, people were convinced the word “streetcar” sounded offensively old-timey.

Then came World War I, which wasn’t a great time for giant projects. Far worse was the Great Depression, during which the city could no longer afford to oil the barrels everyone now wore in lieu of clothes, much less build a subway system. They never got back to finishing it. The tunnels remain there today, carrying no trains. Feel free to break your way in there and explore. If police officers catch you, punch them, right in the nose. Underground, there is no law.

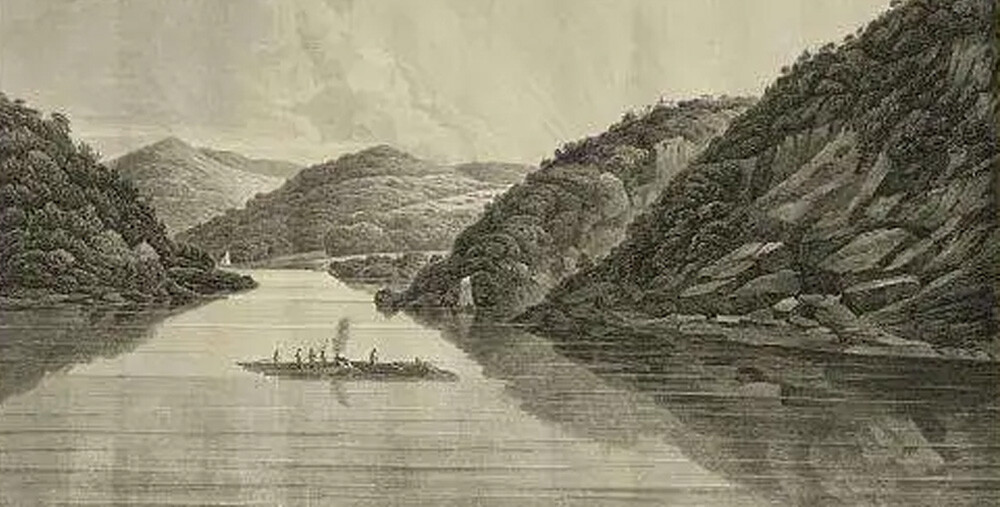

Fort Blunder, to Protect Us Against Canadians

Canada has always been America’s biggest enemy. For proof, look to the previous sentence, which was a joke, or to the War of 1812, which was so embarrassing that several states currently forbid it to be taught to children. By 1818, America had wised up. For starters, they zeroed in on a weak point: Lake Champlain. This body of water between Vermont and New York had repeatedly proven a path for naval ships from the north.

The solution was to build fortifications on the north side of the lake. The fort would be an octagon, which was the strategic shape for combat, according to experts from the world of mixed martial arts. It would sport 125 cannons. If those Brits from Canada came by, America would blast them out of the water. Then we’d play the “1812 Overture,” punctuated by cannons, as soon as someone wrote that piece, about a different 1812 war.

The military spent the 19th-century equivalent of $7 million on building this fort. Then, two years into the project, they realized they had actually been building this new installation north of the Canadian border. They weren’t in their own country and could not operate a fort here. Everyone immediately dropped what they were doing and walked away, whistling innocently.

That proto-fort, built with great expense, totally fell to looters, who carted away all those nifty stones. Today, however, the United States has a different fort at the same site, named Fort Montgomery. They were able to build this because they went and moved the U.S.-Canada border so this spot became American soil after all. This is a simple solution for all problems. We recommend using it at every opportunity.

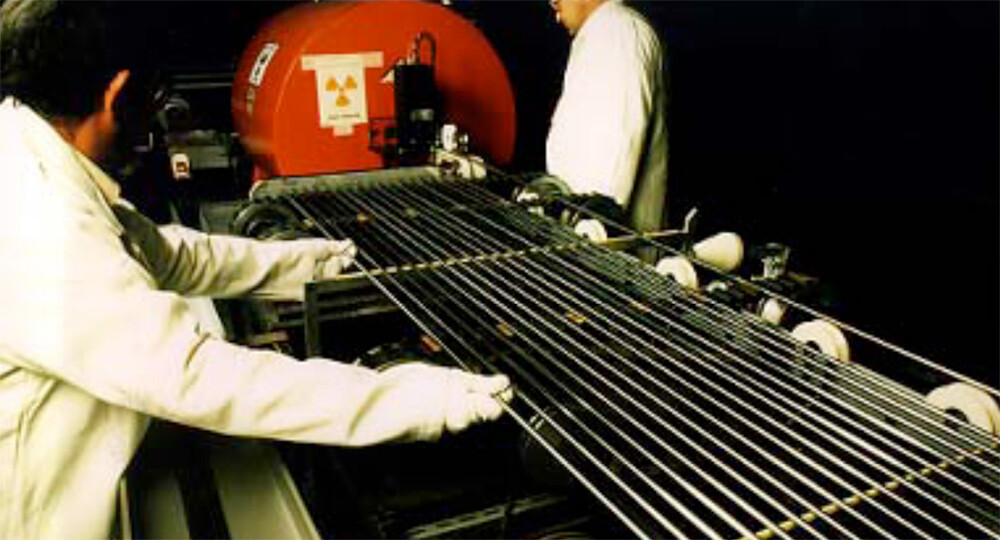

New York’s $6 Billion Nuclear Plant

We know we’ve been throwing around a lot of dollar figures today, so let’s quickly emphasize that $6 billion is a large sum of money. Let’s put it this way — you know one billion dollars? This is more than twice that. Or, let’s put it another way: In 1965, the Long Island Lighting Company announced that they would build a nuclear power plant for about $65 million. By the time the project was done, the actual cost had grown to almost a hundred times that.

The Shoreham plant, once construction completed, connected to the electric grid in 1986. You might remember this as the year of the Chernobyl disaster. That kerfuffle wasn’t great for public attitudes toward nuclear power, and in New York, it increased the anti-nuclear attitudes that had been around since the Three Mile Island accident in 1979. People near Shoreham did not want their plant to ever open.

This mattered because people’s consent was necessary for the plant to open. That was how the law worked: A nuclear plant had to work with communities to draft evacuation plans for the unlikely event of an accident, and if communities refused to draft plans, the plant couldn’t open. You might think this could prevent a plant from ever being constructed, but in Shoreham’s case, it merely stopped it from opening — after they’d already spent $6 billion and two decades to build it. It’s like that old proverb, “A society grows great when old men plant trees in whose shade they shall never sit,” except their children pass a law against anyone sitting under the tree.

The plant had been built with borrowed money, and the task of paying off the debt fell on the public, through a 3 percent surcharge on their energy bills for the next 30 years. They didn’t get any energy out of the plant, of course. Though, in 2004, New York unveiled a set of wind turbines at the site. It will take 35,000 times as many turbines to generate as much daily power as the Shoreham plant would have.

The Squirrel Bridge

Our final story is about a structure far less expensive than any of these others. It also technically was used. It just, well, was not used quite as much as anyone hoped back when they were first approving the idea. This comes to us from the Hague in the Netherlands, home to a chunk of forest known as Haagse Bos:

Close to the forest is an estate called Huys Clingendael, which has its own park.

Between the two runs a busy motorway.

If you’re a person looking to go from one stretch of green to another, that’s not hard. You can walk along the road to the nearest pedestrian crossing. If you’re a squirrel, however, you don’t have that kind of luck or that kind of intelligence. Too many squirrels were getting hit by cars on the N44, decided city officials. So, in 2012, they started building a bridge for the squirrels.

The bridge cost €150,000, which is quite cheap for a pedestrian overpass because most pedestrian overpasses are big enough for humans to use. This one was only for squirrels. The real question was whether squirrels would even know to use this bridge, as that would require a certain level of reasoning and risk assessment potentially greater than the amount needed to dash across the road safely.

The answer came through CCTV surveillance of the site. It revealed that in the first full year after the bridge opened, three squirrels used it. In the second full year after the bridge opened, two squirrels used it. We don’t know how many squirrels used it the year after that, but if the number went up to three again, we hope some city official was savvy enough to issue a release saying, “Usage of squirrel bridge soars 50 percent in one year.”

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.