4 Dudes Who Tried to Prove Themselves and Died Horribly Instead

The Grim Reaper’s hall of fame is filled with guys who died trying to prove what they believed. No, we’re not talking about people who fought for noble causes. We mean stuff like the lawyer who threw himself at a window to show how strong it was, then fell 24 stories to the ground. We mean stuff like the pop star who put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger to demonstrate that it wasn’t loaded. We mean stuff like the biker who took off his helmet to protest mandatory helmets then cracked his skull open.

When you want to prove something, ask yourself, “Might this kill me?” The following dudes didn’t ask themselves that — or they did, and they foolishly went ahead anyway.

John Cummings, Knife Swallower

In 1799, an American sailor named John Cummings visited a sideshow attraction in France. The performer claimed to be swallowing knives. Maybe he was inserting blades down his throat and then withdrawing them, much like the act known as sword-swallowing, which is fairly easy to do. Maybe he was pretending to swallow the knives, through the use of sleight-of hand. Cummings believed the man was doing it for real.

Don't Miss

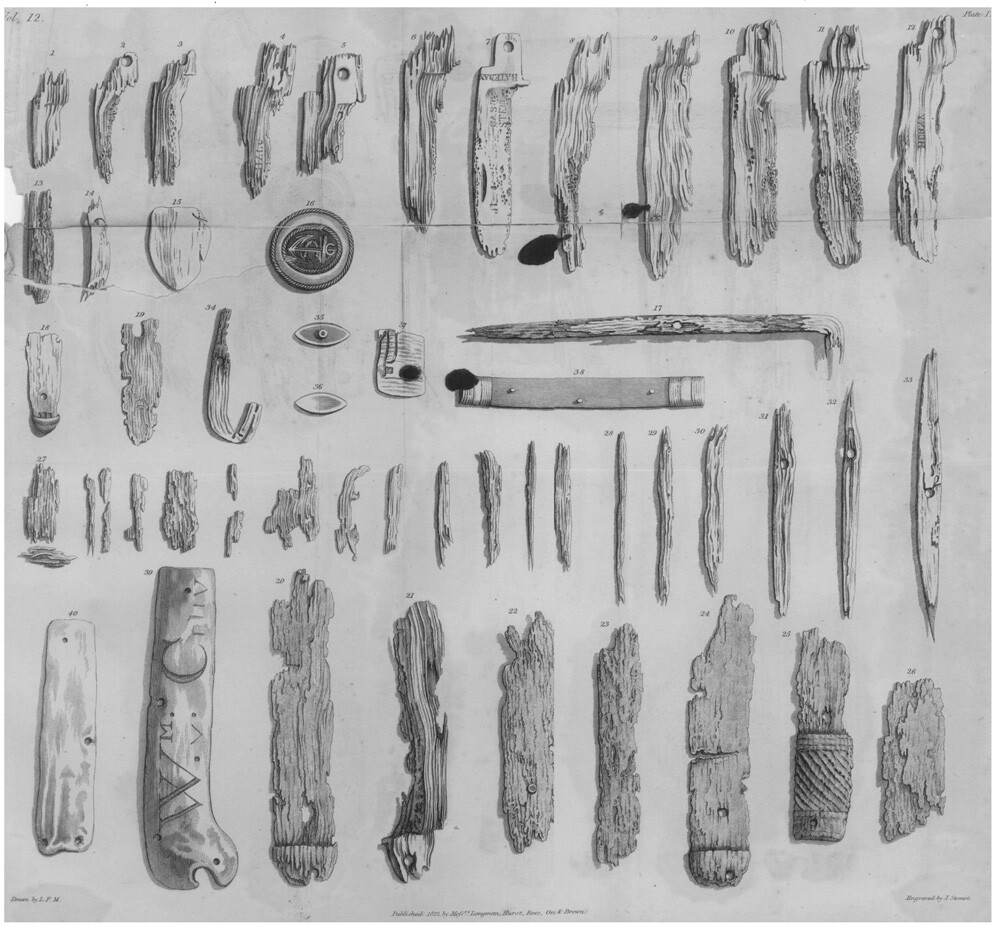

Back on his ship, Cummings told his mates that he figured he’d be able to swallow small knives himself, if he tried. According to the accounts of people on the ship, he then managed to do just that. He swallowed four knives the crew scrounged up. Later, everyone became very interested in his bowel movements, and he managed the pass these knives successfully — though, he did not pass them in the same order as he’d swallowed them.

In 1805, back home in Boston, Cummings related this tale at a party, and everyone understandably figured he was making the whole thing up. Cummings now swallowed a series of knives in front of them. He ingested at least five and maybe as many as 14; people could not agree, since all of them were pretty drunk. These did not pass through him quite as easily. He spent the next month in the hospital, with doctors extracting the blades from him as best as they could.

At the end of the year, he repeated the stunt again, for the sake of a group of sailors as incredulous as the last group. This final knife meal killed him. It did not kill him because the knives ripped his insides open, pouring blood into his intestines. Instead, he spent the next year under medical observation, during which time he wasted away, unable to absorb nutrition. Knives had embedded themselves into his stomach and intestinal walls, not opening giant wounds but keeping his organs from working. Doctors managed to remove some blades, but only after he died could they remove them all:

His stomach had dissolved much of the metal, leaving the knives’ handles. Several body fluids had become laden with excess iron, to the point that magnets could draw the metal out.

An account of Cumming’s autopsy was written by “LATE PHYSICIAN TO GUY'S HOSPITAL.” That may sound a bit informal, referring to Cummings as “guy” like that, but Guy’s Hospital is the place’s actual name, and it has been open in London since 1721. In 1807, it had its own anatomical museum, and if you must die, we can think of few honors higher than your bowel contents being displayed in a hospital museum.

E. Frenkel, Train Psychic

The last days of the Soviet Union saw the airwaves filled with self-proclaimed psychics peddling their craft to the television audience. Among these was E. Frenkel, who said he’d unlocked the secrets of psychic-biological power. He’d managed to heal some people in the city of Astrakhan, according to reports no one’s been able to verify. He also claimed to have stopped “a bicycle, cars and a streetcar” using only his mind.

We can conclude that Frenkel hadn’t really stopped any of those vehicles, but we can’t dismiss the possibility that he thought he may be able to. According to notes that investigators would later discover in his possession, he believed “only in extraordinary conditions of a direct threat to my organism will all my reserves be called into action.” Many people first exhibit the Force when they are experiencing great stress, and Frenkel figured he needed to put himself in a situation where success was the only option.

And so, he stepped in front of a freight train. The train driver saw a man in white get onto the tracks, head facing down. The driver pulled the emergency brake, but it was too late. Frenkel failed to stop the train with the power of his mind. Maybe he would have had more luck with something equally scary but moving with slightly less momentum.

Francis Bacon, Frozen Food Pioneer

We remember Sir Francis Bacon for his works of philosophy, for his works in cryptography and for writing the works of Shakespeare, if you believe in conspiracy theories. He also had some thoughts about food, largely inspired by his own surname.

Keep some meat in your kitchen, and it very quickly becomes smelly and makes you sick. But everyone knows that if you go out into the wilderness, you can find an animal who died long ago and froze, and you can cook its flesh to make a meal that’s safe to eat. What if, theorized Bacon, you could apply ice directly to your meat to make it last longer? This might sound like an obvious conclusion to you, but it wasn’t in England, which had built its first ice house in 1619 and had yet to explore its applications.

In March 1626, Bacon went out in the cold and gathered snow to stuff into a chicken. If this experiment proved successful and he reported the results, he could have jump-started the rush to develop home refrigeration. Instead, shortly after his sojourn in the snow, he caught pneumonia and died. The process of freezing food without ruining it would not be mastered until the 20th century by Clarence Birdseye, a man whose name is now synonymous with frozen food (even more so then Bacon’s is).

Peter Bartholomew, Keeper of the Holy Lance

A group of Crusaders were having some trouble in their adventures in 1098. Then one man among them, Peter Bartholmew, announced something amazing. He had received a vision from God telling him the location of the holy lance, the blade that pierced the side of the crucified Jesus. Conveniently, this location was quite close to where they were crusading.

The men dug at the spot, to no avail. Then Peter told them to close their eyes and pray. When they opened them, Peter stood there with something poking out of the ground. It was the lance, said he, and they were glad to believe him. They went on to great success at killing Muslims, while Peter himself rose from obscurity into political power.

Soon, Peter reported additional visions that were less popular. God was giving him some strange ideas about helping the poor and categorizing people into ranks that left some people less exalted than they’d been. Opponents spoke out against Peter, and he rose to the challenge. To prove God really was on his side, Peter said he would submit to an ordeal by fire. He would walk through flames and would emerge unscathed.

On April 8, 1099 (a day that happened to be Good Friday), Peter went through the ordeal by fire as promised. And just like he’d claimed, he came through it unscathed. His supporters cheered. He'd survived the encounter because he hadn’t exactly walked through flames. The fire had instead consisted of two walls of flames, 40 feet high but a couple feet apart. It was risky but quite survivable, and Peter survived it just fine.

He survived — at least until a mob of supporters approached them, and assassins blending into the crowd repeatedly stabbed him and broke his spine. These wounds killed him within a fortnight. That’s the problem with bending the rules to win. Your enemies can do that as well, and your enemies have knives.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.