5 Hidden Messages People Sneaked into the Media

If you ever find yourself hunting through songs and books for hidden messages, congratulations, you’re a crazy person.

Oh, stories have hidden lessons, both intended and unintended, but we’re referring here to actual hidden communication. We’re talking about words that have been split into their constituent letters and then encoded into publicly accessible media. Many people will overlook the message, but the secret recipients will not.

Don't Miss

No one’s out there burying those kind of messages in plain sight. Except for the people who do.

James May Lost His Job for Sticking a Message in a Car Retrospective

The show Top Gear is currently on hiatus, its future uncertain. Presenter Andrew Flintoff crashed a race car filming an episode late last year, and right now, the rest of the team are thinking of pulling out permanently. Maybe it will return later, with a whole different lineup of hosts. It’s had quite a few hosts in the past, including James May, who was on the show for more than a decade.

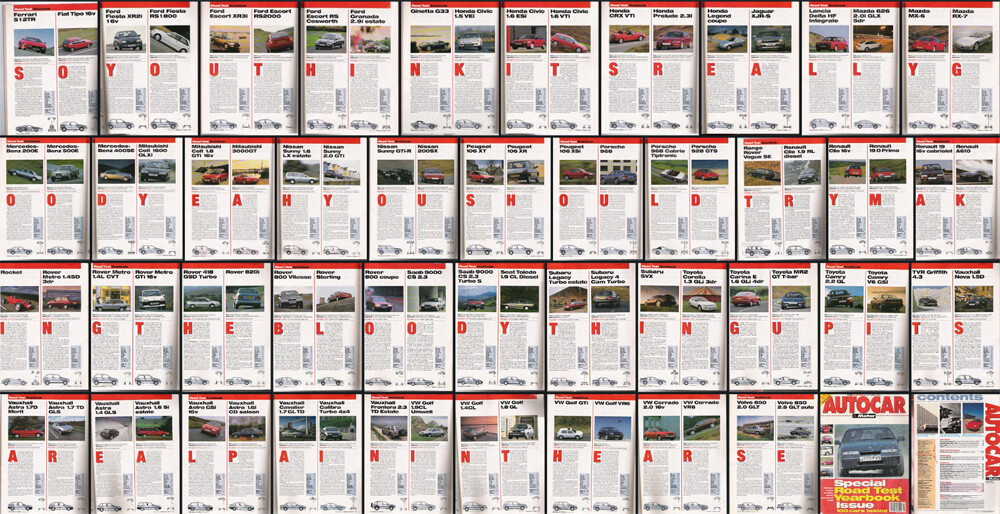

Earlier in his career, May wrote for the magazine Autocar. In 1992, he had the job of writing their end-of-the-year retrospective, which wasn’t so much a writing job as a summarizing job. He had to condense 100 of the year’s reviews down to 150 words each. He spent months working on this creatively unfulfilling task.

To stop his brain from total atrophy, May assigned himself an optional objective. He wrote the extracts so the first letters combined to form a message:

“So you think it’s really good?” read the message. “Yeah, you should try making the bloody thing up. It’s a real pain in the arse.” If you’re spacing out and wondering what “it” is, well, he’s talking about the hidden message itself.

The magazine fired May for this stunt. Which might make this sound like a sad story, but it really hearkens back to the golden age of print media. Back then, a writer could devote months to one piece reworking old content. Readers had no way to mock the result, and they’d even pay to read it.

The Colombian Government Placed Morse Code in a Pop Song

In the first decade of this century, guerrillas in Colombia managed to kidnap a whole lot of soldiers to keep them as hostages. Their captors generally did give them radios, so the government sent messages to the hostages over the airwaves. Families would send over “I love you”s, and the station broadcast them, hoping they’d reach the right ears. The guerrillas heard these messages as well and cackled at them, evilly.

In 2010, the government had some new messages, which they wanted to send to the hostages but not to the captors. The military had managed to rescue several hostages, and they wanted the remaining ones to know this and take hope. Plus, they wanted some hostages to try fleeing. Normally, fleeing is a terrible idea — you might escape your prison, but the jungle will soon kill you — but with rescue operations underway nearby, a breakout suddenly made sense.

If they simply broadcast the message over the radio, the guerrillas would hear it and kill the hostages. The government instead sent it in Morse code, which all soldiers knew but which the guerrillas surely didn’t. They embedded this Morse code in a song, so the dots and dashes would sound like a European dance beat to the untrained ear. The result was called “Better Days”:

Oops, sorry. That was the music video for the 1999 song “Better Days” by Citizen King. Below is the actual “Better Days” song that they produced:

Even without the Morse Code, the lyrics are about someone in captivity. “Although I'm tied up and alone I feel as if I’m by your side / Listen to this message brother.” Then comes the encoded part: “Nineteen people rescued. You’re next. Don’t lose hope.”

Hostages really did get the message, they’d later reveal after being rescued. Plus, millions of people enjoyed the song without detecting any hidden meaning. This was 2010, and the world was otherwise listening to “Tik Tok” by Kesha, so in a way, we were all hostages.

A Headmaster Announced a Teacher’s Retirement by Calling Him a Wanker

Orley Farm School is a prep school in London, and teacher Roger Clark retired from there in 2013. The headmaster, Mark Dunning, announced Clark’s departure to parents with this notice: “We all now know every really great teacher has to finish one day, and Mr. Clark will do so at the end of this term.”

Notice anything awkward or forced about those first words? It’s because they were chosen so their first letters spell out another word: “wanker.” People concluded that Dunning considered Clark a wanker, which is the sort of opinion headmasters are usually supposed to keep to themselves.

Once parents noticed the hidden word and complained, the school edited the newsletter, removing the words “We all now know.” This retained some of the awkwardness but none of the joke. The school's governors next convened, and Dunning announced his retirement right after.

If Harry Potter has taught us anything about how British schools work, Dunning returned later, in triumph, for unclear reasons. And Harry Potter did teach us about how British schools work — in Orley Farm School, students are divided into four houses, each named after some illustrious old alum.

A Student Got the Official Chinese Newspaper to Call for the Leader’s Resignation

In 1991, China’s Communist Party newspaper printed a submission from a graduate student in Los Angeles. It was a poem about birds and the Moon and wind and a bunch of statements about how we must all serve China. “I shall not fail to live up to lifelong aspirations to serve my country,” read one line, while another said, “We must do all we can to catch up and reinvigorate China.”

Not terribly inspiring stuff, artistically. Even the communists who selected the piece surely weren’t inspired by it; they just selected the pro-China poem because that was their job. Mechanically, however, creating a poem like this took a lot of skill because these weren’t just dull words like they sound in English. Each line consisted of exactly seven characters. And now see what happens when you read the poem diagonally starting in the top right and working your way down:

via Sniggle.net

What’s that? You’re not a scholar in written Chinese? Okay, we’ll translate the diagonal message for you: “Li Peng, step down, mollify the people’s anger.” Li Peng was the Premier of China at the time; you might know him best for the Tiananmen Square massacre. Encoding those words weren’t easy at all. “Peng,” for example, relied on a double meaning, a word that also meant “plum.”

The poet escaped punishment because he submitted the poem under a false name. One editor of the newspaper was fired, though. He might also have been executed. We don’t know. The Communist Party newspaper didn’t mention it.

Arnold Schwarzenegger Slipped a Literal F-You into a Veto

California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger was experiencing a touch of friction with the state assembly in 2009. Everyone was arguing over spending, Schwarzenegger crashed a Democratic gala one night, an Assemblyman told him, “Kiss my gay ass” — you know how politics is. When a bill came to his desk shortly after this, Schwarzenegger vetoed it, and he attached the note below.

Run your eyes down the text and check the first letter of each line, and you’ll see a directive that sounds a little less professional than the surrounding language.

When a newspaper asked Schwarzenegger about the acrostic, a spokesman said, “My goodness. What a coincidence.” Sometimes, words just happen to pop up like that.

Obviously, we’re rooting for Arnold Schwarzenegger in this story, because he’s Arnold Schwarzenegger, and because he (or whichever unknown staffer composed the veto) crafted this Easter egg with skill. However, he was still a politician, so you should greet his every move with skepticism.

The bill he was vetoing wasn’t some waste of time about culture warring or something but a plan to convert a disused shipyard in San Francisco into a neighborhood, with restaurants and offices and a thousand homes. A lot of cities have housing shortages, and San Francsisco is maybe the worst. Passing the bill wouldn’t have kept the assembly from addressing prison, health care or anything else listed in the veto. This is a common deflective trick in politics: Avoid addressing one thing by listing other priorities (which you may indeed also plan not to address).

The veto offers a lesson for understanding all political speak. A politician’s words are all just padding wrapped around the true core message, “Fuck you.”

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.