5 Products That Sucked Till We Switched What They’re Made Of

The very first underpants were not a success, as they were made from poison ivy. Everyone who wore them died horribly, leaving no trace, which is why historians today all claim that this underwear never existed and is something we made up. Later, however, tailors switched to materials that made more sense, such as cotton and Fruit Roll-Ups. An invention that didn’t work very well at all suddenly became quite practical to use.

Many other products that seem perfectly fine today used to be utter failures, and people at the time didn’t realize it. People didn’t understand how strange it was, for instance, that...

Hoses Weren’t Waterproof

Don't Miss

For a couple thousand years, we stuck to a single method for sending water at burning buildings: buckets. Long lines of people would pass buckets of water toward the blaze, and this human chain is why a group of firefighters is known as a “brigade.” Buckets did not shoot out much water at once, and they were no good at attacking flames from a distance, or attacking flames at a great height.

Then, starting in the 17th century and becoming much more common after 200 years more, we shifted to the firehose. A hose could take water in from a pump or some other pressurized source and shoot water far, continuously. The firehose sounds like a most obvious invention. It took us so long to make them, not because it took that long to conceive of the idea but because manufacturing an item of that length wasn’t easy. And even once we started making them, hoses had a big defect.

They were made of pieces of canvas or leather stitched together. This meant a hose was prone to leaking, which was bad. A wet hose would also deteriorate and eventually fall apart completely, which was worse. Firefighters had to thoroughly dry hoses out after each use.

They couldn’t hang hoses on long clotheslines, because if they did, water inside the hose wouldn’t drain out. To get the water out, they needed to hang hoses vertically. The most secure way to do so was to build special towers in firehouses, that way the hose could hang several stories and be totally protected from the elements.

In the middle of the 19th century, Charles Goodyear invented vulcanized rubber. Vulcanized rubber meant hoses that could now handle water without leaking or rotting, whether traveling through a rubber garden hose or a firehose that saved on space by combining that rubber with compact linen. As for the ultimate inspiration behind the hose, the penis, rubber was pretty good at sealing that off, too.

Neither Were Sequins, Which Were Made of Jello

Firefighting equipment is perhaps the most important equipment to keep in good working order. Sequins are perhaps the least important. But both did have a similar issue resisting water, which is the one thing they have in common, other than both being associated with strippers.

Originally, sequins were discs of solid metal. Leonardo da Vinci invented a device for making sequins, and far earlier, they had sequins back in Ancient Egypt. These discs were not thin, like sequins today. The goal was to show off a large quantity of metal as a display of wealth. By the 17th century, sequins had slimmed down and might be gilded silver instead of solid gold. They cost less now than pure gold, but they still cost a lot.

With the 20th century, sequins became more popular, thanks perhaps to the discovery of sequins in King Tut’s tomb and the resulting Tut-mania. There was now a wide demand for some still cheaper versions of sequins. And so, our finest sartorial scientists got on the case and came up with a new type of sequin that was cheap and also light. They consisted of gelatin coated in metal using electricity.

Grinding up bones and plating the result in metal sounded pretty metal, even more metal than pure metal. Jello sequins came with a problem, though. Get caught in the rain wearing them, and they’d dissolve away. You wouldn’t be naked, since your clothes were made of normal cloth below the bedazzling, but the sequins would be ruined.

It could get more embarrassing than this, too. These gelatin sequins (or wax sequins) could melt under close human touch. Go dancing and have someone’s hand parked on one particular part of your anatomy? Afterward, there’d be a handprint of melted sequins visible, and your impropriety would be brightly outlined for all the world to see.

Pillows Were Once Made of Rock or Wood

Ancient Egypt was also the earliest source of our next invention, the pillow. These oldest pillows were not polyurethane foam, which did not exist at the time, or sacks of feathers, which did exist at the time. They were headrests made of wood or stone.

People back then saw some advantage in elevating the head, beyond any mild comfort from lying on something soft. Lift your head up a bit, and air would blow under your neck, cooling you down. Hard pillows also offered magical protection. They featured hieroglyphs that asked gods to watch over the sleeper, and while we have not been able to independently confirm the efficacy of these protective measures, carved hieroglyphs are obviously more powerful than ones that are merely embroidered.

You might be wondering if Egyptians really did stick to these hard pillows or whether it’s merely the case that hard pillows were the only kind that left traces for archaeologists. The answer, according to archaeologists, is: Yes, these oldest pillows really were all hard. For comparison, we also rely on archaeology to tell us about Ancient Rome, and here, archaeologists do say they see signs of feather pillows. Also, if some Egyptian back then did try making a feather pillow, it would have immediately been infested with scorpions, making stone the wiser choice for keeping arachnids out of the sleeper’s mouth.

Of course, your own pillow is a delight compared to these ancient unyielding headrests, but let’s not understate how good it feels to have something — anything — under your head. Lie on your side on the grass, and you’ll instinctively slip your hands under there. Your hands might not really be any softer than the ground. To test this out, try knocking a fist into your face.

Crushed Stone Roads Were Considered Deluxe

You sometimes call roads “tarmac.” It’s not tarmac. It’s asphalt concrete. Tarmac was an older substance, and it mixed minerals with tar, while asphalt mixes minerals with bitumen. Both tar and bitumen are called pitch, but they’re different, trust us. Runways, in particular, are referred to as “tarmac” now, but they’re only called that rather than “asphalt” because it sounds cool.

Tarmac is short for tarmacadam. Tarmacadam got that name because it’s a mixture of tar and a previously existing material, macadam. Macadam, meanwhile, got that name from a man named McAdam — John Loudon McAdam. He invented a new road-building process at the start of the 19th century, which became known as “macadamisation” because it’s impossible to say that word without smiling.

Macadam was made from crushed stones, without anything binding them together. Despite that, it was revolutionary, the greatest improvement in road tech in thousands of years. McAdam arranged these stones in a convex manner, so water easily drained off it, and the bulgy roads resisted force like they were a bunch of little arches. They were cheaper than older roads because they required no complex foundations, and they also lasted longer.

These macadam roads seemed great. Then came the invention of the automobile. And when cars rolled over macadam roads, they threw up so much dust that the roads were now clearly worse than cobblestones, worse than dirt, worse than driving on pure flames. Thankfully, people moved on to binding the stones with tar and to binding smaller minerals with bitumen, making the marvelous material today known as asphalt concrete.

Asphalt concrete (informally and wrongly known simply as “asphalt,” or “tarmac,” or even as “macadam” if you’re from Pennsylvania) really is marvelous; that wasn’t a joke. It breaks down over time, but we want roads that we can easily tear up, for various reasons. And when we do break a road down, we can recycle most of that asphalt concrete and use it again. We not only can, we do — it’s the most recycled substance in the world.

Baby Bottles Were Earthenware and Killed So Many Babies

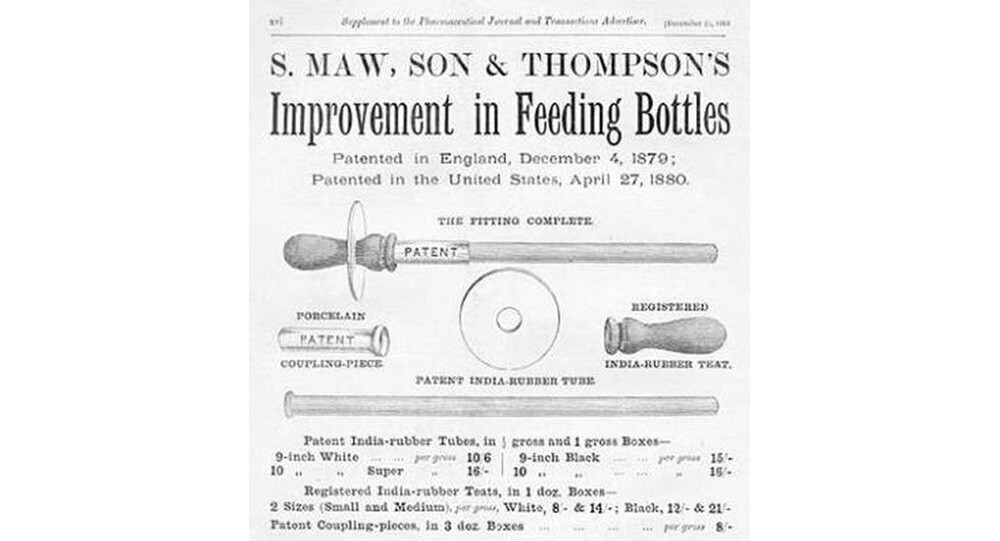

In the Victorian era, there was a commercial baby bottle marketed under the name “The Victorian.” It may sound surprising that people were using the word “Victorian” while they were still living in Victorian days, but they did. The bottle was also called “The National,” “The Empire” and occasionally names that had nothing specifically to do with British pride, like “Mummies Darling” (sic) or “Little Cherub.”

Feeding a baby through a bottle offers many advantages over nursing the kid yourself. This was especially true in the days before convenient nursing attire. In the age of corsets, disrobing took so long that a baby would probably starve to death before ever getting a meal.

As you can see from the photo, the Victorian bottle offered a different design from most that you’ve seen, with a long tube connecting the bottle to the rubber nipple. This let the bottle rest some distance from the child’s mouth, most conveniently.

So, why don’t we let babies drink milk from long rubber hoses nowadays? Mainly because a setup like that isn’t at all easy to clean. Not that people tried very hard — you could let it fester for two or three weeks without cleaning, according to common wisdom. These bottles now have another name, given by historians with knowledge of their consequences: murder bottles.

How many babies died from sucking on these petri nipples? That’s a dead baby riddle we don’t have an exact answer to. It couldn’t have been the only reason that eight out of ten babies back then died before they reached the age of two. But the official consensus is: Rotting murder bottles were a poor choice.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.