The Muppets Take the Funny Papers: The Never-Before-Told Tale of the ‘Muppets’ Daily Comic

During the fifth season of The Muppet Show, there was only one overt acknowledgement that the immensely popular series was ending. In the final episode ever produced, while Gene Kelly palled around with Kermit, the B story focused on Muppet janitor Beauregard, who was convinced the world was coming to an end.

In reality, the show was ending because Jim Henson wanted to expand his horizons with other projects, including fantasy films like The Dark Crystal and the occasional Muppet feature film. But although Muppet fans were losing their weekly adventures with Kermit and the gang, Henson sought to give fans a daily dose of Muppets from a new source: their local newspaper.

Don't Miss

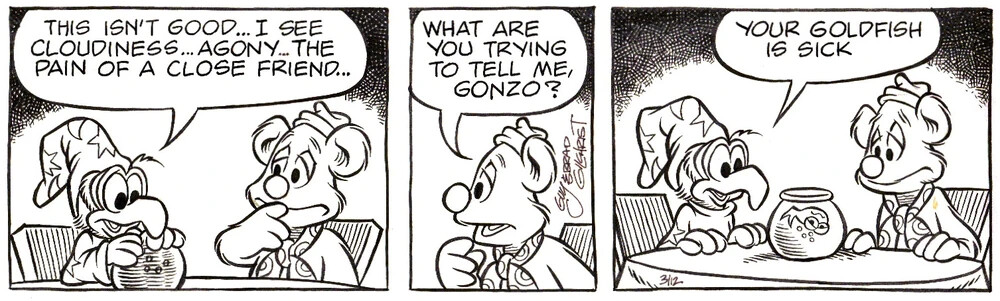

And so, Henson hired young cartoonist Guy Gilchrist to write and draw a comic strip called Jim Henson’s Muppets. It debuted worldwide on September 21, 1981, and during its height, The Muppets strip appeared in more than a thousand newspapers in 80 different countries and continued daily until May 31, 1986. I recently spoke with Gilchrist about bringing the Muppets to the funny papers, working with Henson and finding a fan in none other than the president of the United States.

Funny Animals

In the late 1970s, I was doing an animal comic called Superkernel, and I met Mort Walker, the creator of Beetle Bailey, a couple of times. Maybe a year or so after the second time we met, he was golfing with Bill Yates, the head of King Features, which distributed comic strips. Bill was lamenting the fact that, for about two years, they’d had a development deal with Jim Henson to create a Muppet Show comic strip. They’d tried out about 200 different teams, but nothing was working and they were about to lose the deal. Mort said to Bill, “That’s a frog and a pig, right?” Bill said “Yeah,” and Mort said, “There’s this hippie kid who hangs out at the National Cartoon Museum; he’s pretty good at drawing funny animals.”

Soon thereafter, I got a phone call from Bill Yates in early 1980. He asked me if I knew the Muppets, and I told him I was a first generation Muppets fan from The Ed Sullivan Show and The Jimmy Dean Show and things like that. I was literally a card-carrying member of “The Muppet Show Fan Club.” So Bill gave me a try. There was no 2D art for me to look at of the Muppets except for a few Hallmark cards and Sesame Street books, but I bought everything I could. I drew up some strips — some in the Muppet Theater, some outside the theater — then I brought them in and Bill liked them.

Eventually, I found myself in the Muppets headquarters, Jim Henson’s famous brownstone at 117 East 69th Street. I met Michael Frith, vice president of Henson Associates, who gave me some pointers, but nothing was official yet — and wouldn’t be for a while.

For the next 10 months, whenever I wasn’t working on Superkernal or whatever books I was doing for Disney, I was writing and drawing more Muppets strips and sending them into Bill. Bill would call me and say, “I can’t pay you for these.” I just told him, “That’s okay.” After almost a year, the phone rang, and it was Bill Yates saying, “Something’s going on over at Henson. I don’t think it’s good for you, but I think they made a decision.” The next day I got a phone call from Jerry Juhl, Jim’s head writer. He was throwing out some ideas for scenarios. Finally, I asked him, “Mr. Juhl, why are you calling?” He said, “Didn’t anyone call you? You’ve had the job for a month or so.”

Meeting Jim Henson

After about a month or two of me working on the strip for real, my brother Brad, who helped me write some jokes, and I were asked to come and work out of the office for a week. We were put up in the Waldorf Astoria and came into the brownstone every day to work. That Friday, Jim flew in from London, and on that Saturday, we met for the first time.

I was sitting with Brad in the conference room on the first floor, and I was so nervous. Our meeting was at 11 a.m., but I think I showed up at like 7 a.m. and was just drawing — what else was I going to do? Around 8 a.m., the door opened and there was Jim with a knapsack on his back and this glow around him. He looked at us and said, “Oh, you must be Guy and Brad. You’re early.” Then he smiled and said, “I’ll see you in a little while,” and walked up the stairs to his office.

Later on, Brad and I sat with Jim as he complimented us on the stories. Then Brad left and it was Jim and I left to talk about the art. Jim said, “You know, Guy, some of your drawings are very, very good, and some of them are great, but we want wonderful.” Next, Jim held up his hand and introduced me to Kermit. Kermit wasn’t on his hand, he just introduced me to Kermit. He drew a quick picture of his hand with a ping-pong ball cut in half on his knuckles, handed it to me and continued to talk like Kermit. Only then did it hit me exactly what he meant.

I was used to drawing two-dimensional characters that weren’t my own and adapting myself to work in that style. But with the Muppets, there was life coming right out of Jim’s hand. They were three-dimensional, they moved, they had color, they had actors inside of them. There was a world of music and voices and wonder, and that’s what Jim wanted me to draw. That changed me forever.

This was the way Jim taught. He didn’t tell you things; he had respect for you and he respected his own judgment about who he wanted to work with, so he wanted you to discover what it was what he was thinking so that you would merge and creatively partner with him.

Working on ‘Jim Henson’s Muppets’

Ironically, to achieve what Jim wanted, I had to make the characters less puppet-like. I had the puppets to look at and there was a style guide that showed how the characters looked from each angle, but it was very technical and my job was to take that, learn it and then go another step. If I just drew the puppets in black-and-white, it would be missing all the wonderful stuff Jim was talking about. Over time, I began to animate the characters — make their eyes bigger, make their faces do things the puppets couldn’t. It was an abstraction of the characters because the puppeteers weren’t in there to do it.

The hardest to translate was Piggy. There’s a softness to her snout, but it’s big, and if you draw it as big as it is, it doesn’t look like Piggy anymore. You also imagine her eyes to be huge, but they’re quite small in reality. I wanted to keep her adorable. Besides Kermit, Rowlf was my favorite character to draw because I grew up with him. I always saw him as the heart and soul of the Muppets — and if you take Kermit and Rowlf and put them together, you get Jim.

‘The Muppets Don’t Belong to the United States, They Belong to the Whole World’

The comic strip was hugely important to Jim. At some point, I guess it was around 1978, he knew they’d stop production of the weekly show and he wanted to be sure the characters continued in people’s homes all around the world. With that, before we began production, Jim met with King Features and said, “The Muppets don’t belong to the United States, they belong to the whole world, so I would like everyone in the world to read the same strip in every language on the same day.”

The guys from King Features were on the floor — this had never been done before. But Jim said, “Whatever Guy draws that you’re reading in The Daily News, is the same one everyone will be reading.” They said, “Mr. Henson, this cannot be done.” And Jim just said, “Oh, I think it can.” Then he thanked them, said goodbye and returned to London.

Jim was extremely gentle and soft-spoken. He didn’t say a lot, until there was something to be said. Jim would always listen, and then he would make a statement, to which everyone listened. Muppets producer David Lazer used to say, “Jim has a whim of steel,” which described Jim perfectly.

And so, King Features made it happen — the strip was in every country with a free press in every language. That was over 80 countries. We were the only comic that was ever like that. And that was because of Jim’s vision.

It was also because of Jim that I was a guest of honor at the White House in 1984. I got a call one day saying, “President Reagan called and told us that The Muppets is his favorite comic strip. They had asked Jim to be guest of honor at the White House during the Easter Egg Roll, but Jim said, ‘That’s not me, that’s Guy. Send Guy. He’ll like that.’”

The Final Strip

Our contract with King Features was up in 1985. It was a five-year contract, and at the time, the Muppet Babies were huge and Fraggle Rock was huge. I put forth the idea to do a week of the Babies or a week of the Fraggles, but King Features didn’t want that. They wanted Kermit and Piggy to be Dagwood and Blondie, but that’s not who they were.

For about a year, I continued to draw the strip without a contract. Meanwhile, I had so much other stuff I was doing for Jim and my children’s book career had taken off that after a year without a contract, I spoke to Jim and we decided that, if they didn’t want to continue it the way I wanted, it would end.

It was upsetting, but I know Jim was happy with me. The last time I met with him was late in 1986, months after the strip had ended. I was talking about one of my projects, and I noticed something on the wall behind him. It was the wall where Jim kept his Emmys and so many of the other awards that he’d won. On that wall I noticed, in a frame, with a light on it, was the original artwork for the final Sunday strip I’d ever done.

Boy, oh boy, have I held onto that memory.