Meet the Newspaper Cartoonists Replacing Scott Adams and ‘Dilbert’

Dilbert is dead. Well, he’s not dead dead — Scott Adams took a minute in-between his bigoted geyser eruptions to announce that Dilbert is still being published on some z-list Patreon KKKnockoff — but as far as the public-at-large, and especially newspapers, are concerned, Dilbert is deader than a doornail.

Click right here to get the best of Cracked sent to your inbox.

If you need a reminder, back in February, Adams went on a racist tirade. Again. His then syndicator, Andrews McMeel Universal, dropped him and Dilbert, with the strip removed from approximately 2,000 newspapers. This left a literal blank spot in those newspapers, and different comics — some new, some with longstanding followings, none responsible for anything as stupid as the Dilberito — filled the void.

Don't Miss

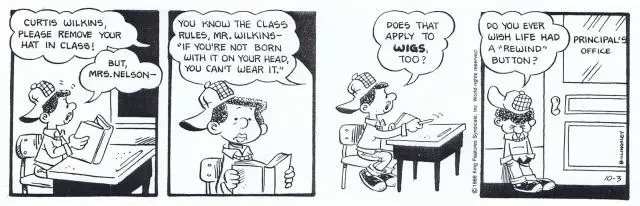

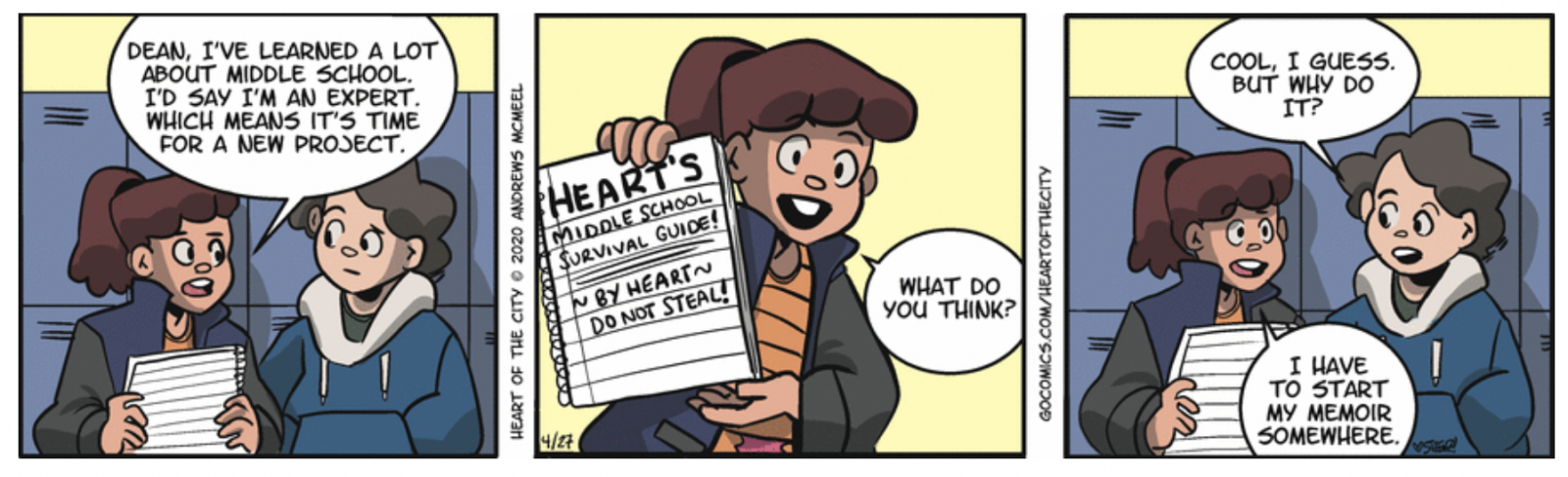

In place of Dilbert, numerous newspapers have decided to replace Adams with creators of color — a move that’s not only symbolically important but helping diversify a field traditionally dominated by white voices. Three of these creators are Ray Billingsley, creator of Curtis; Tauhid Bondia, creator of Crabgrass; and Steenz, who took over as the artist and writer of Heart of the City in 2020.

I’ve gathered them below to talk about their background and influences, the creation of their own strips and how they feel about filling Adams’ hideous, hideous shoes.

What were your comic strip influences growing up, and what drew you to newspaper comics more generally?

Tauhid Bondia, creator of Crabgrass: My first real memories of reading comics were the Garfield collections from my school and local library. The teacher would send us all to the library and tell us that we had to check out one book. A few of us found a loophole that the Garfield comic collections were included as reading material.

I’ve been creating comic strips for decades now. In fact, I did a comic strip for my high school newspaper called School Daze, which was very poorly drawn and written. It was a blast, though; everyone in school knew about it. It was one of the few things that made high school easier. After that, I was always doing some comic strip and publishing it on the internet, right up until creating Crabgrass in 2019.

Steenz, artist and writer of Heart of the City since 2020, winner of the Dwayne McDuffie Award for Diversity in Comics in 2019: I had grown up reading newspaper strips. I feel like newspaper comics are the first comics anyone reads — at least it was back in the 1990s. My favorites were Curtis, Jump Start and Cathy. I also would get dropped off at Borders and would read those big Zits and Calvin and Hobbes books for hours on end.

I grew up being interested in art but not really knowing what I wanted to do with it. After going to art school, I eventually got into reading comics, and I worked in a comic shop. Reading more and more of them, I eventually got more interested in the people behind the comic books. One comic was Samurai Jack by Brittney Williams. I’d been following them on Tumblr for a couple of years, so I knew that they were Black, that they were fem, and suddenly things all started to come together — “I should be making comics!”

Comic strips are a somewhat small, closed-off field, how did you break in?

Ray Billingsley, creator of Curtis, first Black recipient of the Reuben Award for Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year in 2021: I started young — I was 12 years old when I got into the industry. It was sort of a sad thing, though. I didn’t come from the very best of families. My father was a real tyrant, and I spent a lot of time in my room just drawing because I was afraid of him. We didn’t have friends over, we didn’t celebrate birthdays. Most holidays we didn’t do anything because of him.

But through drawing, it helped soften the blows of what life was like. From about age 10, I started carrying a pad and pencil with me everywhere. Then, in seventh grade, when I was 12, the art class was doing this recycling program. The class was constructing this aluminum can Christmas tree, and I went to the side and started drawing. There were some news people there, and a woman approached me and asked what I was doing. I showed her, and she asked if she could have them. I said, “Sure” — this was 1969, and back then, you didn’t have to worry as much about being snatched up or touched or anything.

Anyway, she asked for my number, and I gave it to her. The next Monday, she called the house and came to find out, she’s the editor for a kids’ magazine. She wanted me to do some drawings to go along with some articles. My mother took me down there, and I did these drawings and they bought them. I got $5 a drawing! I was rich! I bought a hot dog and some Hot Wheels.

I didn’t know I was starting a career at that point, but I was. They gave me more and more to do, and before long, I was signed on as a staff artist at 12 years old. Every day after school, they sent a car for me, and I went to work.

Bondia: It’s hard to break into the club of syndicated comics, especially nowadays. There are so many legacy strips out there that have been around forever that get passed on to different artists and different writers, and there are fewer and fewer spaces in the newspaper for them and a lot fewer newspapers. The major syndicates only really launch one new strip every year or so. The competition is as stiff as ever, too. There are still a lot of people who have the dream to be syndicated.

I was really fortunate. If I had an “in,” it was that, before being syndicated in newspapers, I was digitally syndicated on Go Comics with a strip called A Problem Like Jamal. Shena Wolf of Andrews McMeel Universal had reached out to see if I wanted to publish that strip digitally, and when I came up with the idea for Crabgrass, I reached out to her.

Steenz: I found a local group here in St. Louis that does anthology comics. Then another friend and I began doing a webcomic, but before we published, Oni Press was looking for submissions, so we pitched it to them and got in and ended up winning the Dwayne McDuffie Award for Diversity in Comics in 2019 — that really kick-started my career.

I began working at the St. Louis publisher Lion Forge Comics in their editorial department, but I got laid off when they merged with Oni Press. I began doing freelance artwork. Then an editor named Shena Wolf found me at the Small Press Expo, and she said, “You’re incredibly organized, you’re goal-driven, and you can take an established character and update it for a new audience. How do you feel about syndicated newspaper comics?”

What about the origins of your particular strips?

Billingsley: Beginning in the 1980s, I would send new strip ideas to the syndicate every year, but nothing took until Curtis. I think it clicked because it was a unique take. There were no full Black families in comic strips back then.

Curtis’ family is what I wished I would have had growing up, but I still wanted some realism in there. Like, Curtis was the first comic strip where the kids actually got in trouble. Dennis the Menace always got away with everything, but I wanted to break the mold on these kinds of things. I wanted him to actually fight with his brother. There were also too many strips with the kids outwitting the parents. I wanted parents who were clever, who were onto his BS and who treated him accordingly.

Bondia: Crabgrass is about friendship. When I’m writing, I like to go back to that time period where friendship was in its purest form. The very first strip is lifted from my own history. When I was 10, and my family moved to Greenway Drive, I was kind of underfoot, and my mom pointed to these children I never met and said, “You see those kids over there? Go play with them.” So I went over there and said, “My mom says I have to come play with you.” And we were best friends from that moment on. I love that about childhood friendships, that all that’s required is proximity.

I know it’s a little different for you, Steenz. What’s it like taking over a strip for someone else?

Steenz: When I met Shena Wolf, she explained that they were looking for someone to take over Heart of the City, which had been a comic created by and done by Mark Tatulli since 1998. He wanted to retire, and he sold the comic to Andrews McMeel. So they reached out to me to update and revamp it. After a four-week audition, they offered me the job, and I’ve been doing Heart of the City every day since.

When I got started, I was a little worried that I’d be the odd man out, but I didn’t feel like that at all from the other creators. They were all like, “Welcome to the team!” I also got emails from Billingsley from Curtis and Robb Armstrong of Jump Start, and they were both like, “Hey, welcome! We’re happy to have another Black person here!”

Okay, let’s get into Dilbert. What were your feelings about the strip itself before Scott Adams went so publicly off the deep end?

Bondia: Back in the day, I loved that comic strip. It came around during that snarky time in my life. I was a kid, and that’s what I thought being funny was. I also loved the TV show when it came out — the theme song slapped.

Steenz: I read the comic growing up, but I stopped reading Dilbert after a while because it was the same stuff over and over again. I do remember liking that TV show when it was on Adult Swim. Maybe I should go see if it’s on Paramount+ or something — I’m kidding, of course.

Billingsley: Dilbert was all about office life, and because I got into this business at 12, I’ve never had a job, so I couldn’t relate to it. But more importantly – I’m going to give you a little truth here – I have a high threshold for artwork. I like good art. I like people who can relay emotions and draw close-ups and scenery. Dilbert was none of that; Scott Adams is not a very good artist.

In the comic strip community, did you hear anything about Adams before this all went down?

Billingsley: In the industry, we’d heard different stories that Scott was a dick. So we knew he was a dick, but we didn’t know how big of a dick. He had run-ins with other cartoonists before, people who I knew who were genuinely nice people, but he had never mentioned a disdain for Black people.

He didn’t come to meetings or anything like that. Nobody cared. Nobody misses him. We knew about arguments he’d had with people, but we sort of wrote him off. For most cartoonists, if you’re a negative person, we leave you alone. We just don’t pay attention to it. Cartoonists are one of the most accepting groups you will ever find. If you can draw and you’ve got some humor in you, we love you.

Steenz: I didn’t keep up with Dilbert, but I did hear about all the trouble Scott Adams was causing. I was aware that he was a tough creator for the syndicate to work with. I remember talking to my editor and them being like, “Ugh, we’re dealing with Scott Adams stuff.” So I knew things weren’t going well behind the scenes. Then, it really started to blow up this year when he got more and more outspoken about his hate.

Bondia: Scott Adams was on that trajectory for a while. People who pay attention to comic creators were aware of that. He’d also been doing his podcast for a while, which was a bubble of all like-minded people in this echo chamber, and I think he got used to that. He thought what he was saying would stay in that bubble, but the mainstream caught wind of it.

It’s unfortunate because I do remember enjoying the strip. It’s a shame that something like that would get marred by the behavior of the creator. But, hey, it created a fantastic opportunity for me, so I can’t be too mad about it. If you’re a public figure, it’s part of an artist’s job to expect that their success will be tied to their personal behavior. I think that’s fair. People have to be more careful today, but that only encourages better behavior, so it’s hard to look at that as a minus. It’s a cautionary tale to me.

Steenz: I hope Scott Adams understands the irony of him saying those things about Black people only to see his comic taken over by Black people.