Five Severed Body Parts That Nearly Accomplished More Than the Famous People They Belonged To

If a bit of you gets cut off, that sucks, but if that detached body part goes on to lead a more interesting existence than the rest of you, damn, that has to really suck. It’s certainly not unheard of. In fact, it’s even happened to quite a few famous faces — and other assorted bodies parts. Such as…

Napoleon’s Penis

Napoleon (1769-1821) saw a lot of the world during his lifetime, but his penis is the best-traveled part of his body, having continued to have adventures long after the man himself died. After Napoleon’s death on the island of St. Helena, an autopsy was arranged. During this, Napoleon’s physician François Antommarchi cut his penis off. Nobody is entirely sure why — it might have been an accident, or he might have been paid to do it by a grudge-bearing chaplain who Napoleon had offended.

Either way, the penis went to the chaplain, who took it home to Corsica and handed it down through his family. In 1916, after 95 years of being disembodied, the penis was sold to an antiquarian bookseller, who in turn sold it to another, who arranged for it to go on display in New York. It changed hands several more times over the next few decades — all documented in the impressively alliterative Journal of Sex Research paper “The Peripatetic Posthumous Peregrination of Napoleon’s Penis” — with its occasional public appearances leading to various unflattering descriptions. It has been variously said to be tiny, shriveled, jerky-like and “like a little baby’s finger.”

Don't Miss

In 1977 it was purchased by urologist John K. Lattimer (who also owned drawings by Hitler, Goering’s leftover cyanide capsule and Abraham Lincoln’s blood-soaked collar). On his death, it passed to his daughter, who doesn’t seem to want to sell it. Napoleon’s severed penis might just be sitting in a cupboard somewhere, tiny and shriveled, thousands of miles from his balls.

Jeremy Bentham’s Head

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) was a philosopher and ethicist who came up with the modern idea of utilitarianism. He was ahead of his time, in favor of women’s rights, animal rights and decriminalizing homosexuality, as well as abolishing slavery and capital punishment — all pretty radical views for the 18th and 19th centuries.

When Bentham died, he arranged for his body to be dissected and turned into an “auto-icon,” a lifelike memorial incorporating his skeleton and preserved head. The skeleton side of things worked fine, and Bentham’s bones were dressed in a suit filled out with hay. The head was a different matter though — the preservation method used by his friend Thomas Southwood Smith left a little to be desired, and the result was pretty terrifying-looking. Southwood Smith was trying to emulate a mummification technique he had heard was used by indigenous New Zealanders, but what he ended up with was a horrifying, tight, leering, shit-brown reminder of death.

The head was too grim-looking, so a wax version sat atop Bentham’s body instead, the real one sitting in a case at his feet at University College London. However, the head was slightly too stealable, and was pilfered and returned many times. In 1975, students from the rival King’s College London kidnapped it and demanded a ransom to be paid to charity. Another time it went missing and is said to have been found in Aberdeen railway station, over 500 miles away. An occasion on which it was used for soccer practice is said to have gone too far, and the head has been kept under lock and key since.

The Globe-Trotting, Split-Up Body of St. Francis Xavier

St. Francis Xavier (1506-1552) was the co-founder of the Jesuits and traveled extensively around Asia, working as a missionary in Spain, France, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, India and Sri Lanka. He died on an island just off the coast of China, and was originally buried there. However, when another group of missionaries dug the body up several months later, it was in perfect condition. It was taken to Malaysia and buried again, then dug up another time and taken to Goa in india, where it was put on display to show how perfectly it was preserved.

This is when it all started to go a bit taking-a-LEGO-man-apart — first a Portuguese woman bit off his big toe, which gushed startlingly fresh blood. The toe remains on display in Goa, along with a fingernail, kept in a different village. His right forearm was cut off and sent to the main Jesuit church in Rome, and his upper right arm has been housed in several different churches in Goa. In 2017, his right forearm was taken to Canada for a rock band-style tour, stopping at dozens of cities on the way. His left hand may or may not be in Japan.

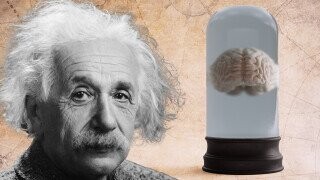

Albert Einstein’s Brain

When Einstein (1879-1955) died at the the Penn Medicine Princeton Medical Center in New Jersey, the doctor performing the autopsy made a move that could charitably be described as “cheeky”: he stole Einstein’s brain.

Dr. Thomas Stoltz Harvey didn’t have permission, or indeed ask for it, before pilfering the most celebrated cerebellum in human history, although he later said, “I just knew we had permission to do an autopsy, and I assumed we were going to study the brain.” Harvey wasn’t a neuroscientist, but hoped that studying it might shed some light on Einstein’s genius. He later got slightly begrudging retrospective permission from Einstein’s son, on the condition that everything gleaned from the brain would be used only for science and published in reputable journals rather that sensationalized or treated as a novelty.

Harvey was asked by Princeton to give it up and refused, so was fired. He then had the brain sliced into 200 sections, most of which were kept in jars in his basement. Over the following decades the brain traveled the Midwest with Harvey through various job losses and a failed marriage, at one point being stored in a cider box under a beer cooler for a few years. In 1997, he drove from New Jersey to California with the brain in the trunk of his Buick to meet Einstein’s granddaughter, then accidentally left it behind afterwards. Some sections went to Japan, some to Princeton and UCLA, but the majority is now in Washington, D.C., in the National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Joseph Haydn’s Skull

The famed composer Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) died in Vienna at the age of 77. After he was buried in the Hundsturm Cemetery, two acquaintances bribed the gravedigger to dig him up again, remove his head and re-bury the rest of him. Joseph Rosembaum and Johann Peter were interested in phrenology, the idea that intelligence and other traits were determined by the shape of the skull, and wanted to study the skull of a genius.

After a few mishaps, including Rosenbaum vomiting upon being delivered the decomposing head, they were satisfied that Haydn’s skull had the bumps on it that would befit a genius, and it was boiled, bleached and boxed.

In 1820, a prince arranged to have Haydn reburied in a fancier grave, and was livid to find his head missing. Rosembaum and Peter were the chief suspects, but managed to hide Haydn’s skull in a mattress, which Rosenbaum’s wife lay on while loudly claiming to be on her period — the head-hunters left her to it and looked elsewhere. Eventually, Rosenbaum got hold of a different skull by fairly dodgy means and gave that to the prince.

Over the next century or so, the real skull changed hands several times, including a period under the ownership of the Viennese Music Association. In 1954, it was placed, along with the rest of his body and the subbed-in skull, into a new marble tomb, making it look a lot like the reason for his genius was that he had two heads.