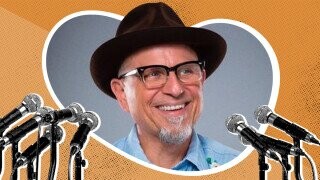

Bobcat Goldthwait on Mourning Robin Williams, Annoying Jerry Seinfeld and the Importance of Quitting

On his new stand-up album Soldier for Christ, Bobcat Goldthwait does a routine about getting a colonoscopy. He talks about getting mailers from AARP. And he admits to having erectile dysfunction. “I can’t believe I’m telling Viagra jokes,” he says, and then lets fly with a couple pretty damn funny ones. He is 60, but the album isn’t just about getting older — it’s about reflecting on a childhood spent tormenting nuns, remembering friends who have died and taking stock of a career that saw him get very famous for things in the 1980s that he’s since distanced himself from. Back then, he was known for being part of the Police Academy movies — and for performing stand-up in a screechy, demented voice, playing a hyper-anxious character who seemed ready to implode at any moment. That guy is nowhere in evidence on Soldier for Christ. Years ago, Goldthwait retired the voice and the on-stage shtick, and now he’s just himself. As this intimate, hilarious and occasionally touching set suggests, that’s more than enough.

If you’re not aware of this new Bobcat Goldthwait, he’s not perturbed — but you do have some catching up to do. In the past decade-plus, he has stopped acting to focus on independent filmmaking. It was a career shift helped by his friend Jimmy Kimmel, who tapped him to direct Jimmy Kimmel Live! in the mid-2000s, providing Goldthwait with a steady gig. But soon, the controversial auteur of the divisive 1991 dark comedy Shakes the Clown was pursuing even more provocative films, starting with 2006’s Sleeping Dogs Lie, in which a twentysomething teacher, played by Melinda Page Hamilton, sends shockwaves through her community when she admits that, as a teenager, she gave her dog a blow job.

Goldthwait followed that up with World’s Greatest Dad, starring Robin Williams as a failed writer whose teenage son Kyle Clayton (Daryl Sabara) accidentally dies during a bout of autoerotic asphyxiation — Williams writes his boy a suicide note to spare the kid any embarrassment, only to discover that Kyle’s schoolmates find his words inspirational, prompting this dad to compose more missives in the fake voice of his dead son. And then there was God Bless America, a Natural Born Killers-style satire about an older man (Joel Murray) and a teenager (Tara Lynne Barr) who hit the road to take out their anger at everything they despise about this hellish country. (And to think: God Bless America was made before Trump’s presidency.) Do any of these movies sound remotely funny? Well, they are — and surprisingly poignant at times, too.

Don't Miss

Click right here to get the best of Cracked sent to your inbox.

Speaking from his home outside Chicago, Goldthwait has a laid-back sense of humor, but he’s not worrying about being “on,” a quality he shared with Williams, his best friend whose death in 2014 still affects him. (When he quotes the late comic, he does a perfect Robin Williams impression.) Whether talking about comedy or filmmaking, the warm, white-bearded Goldthwait is introspective, unafraid to open up about how he’s grown as a person or what frightens him. But he’s mostly excited: He’s recently finished a new script, which he describes as a sincere, G-rated kids’ movie — and, yes, he realizes that’s not the sort of thing you’d expect from him. “The scariest thing as a filmmaker is to actually write a personal movie that’s not offensive,” he says. “That is terrifying, because then you’re saying, ‘This really is me.’ Before when people didn’t like my movies, I’d say, ‘Well, you’re square. You don’t get it, man.’ To say, ‘This is me’ is terrifying. But I’ve always gravitated to the things that scare me.”

Maybe that explains why he’s so fearless — albeit, fearless in a different way than he was earlier in his career. Perhaps you remember the Bobcat Goldthwait who terrorized talk shows in the 1990s, literally ripping up shit and setting things on fire. That might be seen as anarchic and nervy, but for him, such antics were quickly becoming a dead-end. It was time to do something different. And so he turned his back on what made him famous and hoped enough people would follow along on his new path. He knew not everybody would. (On Soldier for Christ, he responds to an imaginary online troll who threatens to unfollow him by saying, “I used to play arenas. Millions of people have unfollowed me. You’re really late to this.”) But by doing stand-up and making films — and sometimes combining the two, like on his 2020 concert documentary Joy Ride — he has continued to pursue his muse, happily not hovering in the spotlight as much as he used to.

During our hour-long conversation, we talked a lot about Robin Williams, his move to the Midwest, how he feels at 60 and what the deal is with Jerry Seinfeld hating his guts. Goldthwait is a soulful dude who, blessedly, hasn’t turned out like so many aging, reactionary comedians moaning about cancel culture. (He has some thoughts about his peers who have gone that way.) It’s hard to imagine the younger, hollering Goldthwait ending up as an enlightened, thoughtful, well-adjusted guy. But as he tells me, that public persona was never him anyway.

On the new album, you mention you’ve moved to Chicago.

I actually live about 50 minutes outside of Chicago. I live in a small town. It’s part of the federal witness relocation — no, I live on a dead-end street in the woods in a town of 2,000 folks.

You joke that one of the unexpected advantages of moving is discovering you’re actually thin by Midwest standards. But what was the reason you got out of L.A.?

My girlfriend’s family lives nearby, and I got tired of the fires and everything else. I lived in L.A. for 35 years, but during the pandemic, I edited Joy Ride, a documentary I did with Dana Gould and myself. I was editing with an editor in New York and I was like, “I guess I could just live anywhere now.” So then we moved. And it was funny: When we moved, we bought the house online without seeing it — I mean, just pictures. And we walked in and we didn’t like it, because our imagination had made it different. And now we love the house. But it was pretty weird: The realtor’s like, “Do you want a photo of you outside your new home?” and we’re like, “No. No, we don’t.” (Laughs)

Has it been hard to adjust after living in a big city for so long?

I love it. I mean, it’s almost two acres, and most of it buttresses up against woods. My daughter’s funny: She’s like, “Dad, you used to talk about cinema, and now you talk about the woodchuck you saw.” Which is true. I feed all these animals: I put puppy chow out for the woodchuck.

You don’t miss having access to indie movie theaters and other big-city perks?

None of that, because I just drive into Chicago. I recorded this album by doing a residency at Lincoln Lodge, so I would go drive in once a week, and instead of doing my greatest-hits act like I do on the road, I would just tell stories and get a lot more personal. Then I eventually recorded it. Some of these bits became routines, and they became tighter. But I do like that the album — hopefully, if it works for people — is really accurate in regards to sitting in the audience with me. Hopefully you can catch on that there’s a lot of that stuff in that album that’s not scripted — it’s kind of me manipulating a dinner conversation.

Some of Soldier for Christ you’ve done in previous sets — your Nirvana story, for example. Was part of the appeal to preserve these bits all in one place?

Some of the stories I’ve done before — I’ve done bits of them. There’s a couple bits that are my big closers that I didn’t put on the record just because I felt like I’ve done them too many times. (Album producer) Melissa (Weiss), who edited it, was really great: She listened to (earlier) specials of mine and she goes, “Naw, you did that bit before.” She’s very comedy-adjacent, and she would go, “There’s a lot of people that talk about that.” I’d go, “Oh, I didn’t realize that!” So we’d cut that out. The actual show was almost two hours long.

There’s a segment, “Robin and I,” where you’re inspired to talk about your friend Robin Williams because you walked by a huge image of him on the way to the show. You seemed a bit shaken by seeing that.

Oh my god, it’s this mural outside the club. I’m not kidding you: Every time I walk in there, it’s like a smack in the face. And I get it — everybody loves the guy and they should — but it just has a different impact on me. Sometimes I’ll see a picture of him and it reminds me of who he was to hang out with, and then I’m cool. But other times when I see him, it’s this other thing — I don’t get mad, but I get sad. And I think I get sad because I’m going, “That’s not the guy.”

Now the weird thing is, I kind of hold some of the keys to who he really was, but I also feel like we were really close simply because I didn’t blab, so why would I blab now? I was with his widow and Billy Crystal, and Billy says, “He really liked everybody,” and I started laughing — I thought he was making a joke. I go, “He didn’t like a lot of people.” And then (Williams’ wife) Susan goes, “Well, you were the person that he told.”

I think anybody who goes through grief, there’s that process of wanting to share with others the person that you knew because then that keeps that person alive. But it’s different when it’s a celebrity: Some of those things are secret.

People don’t want to hear some of it anyways. They don’t want to understand that Robin wasn’t “on” all the time — that was kind of a myth that even he perpetuated. But, no, we would have very… I mean, we enjoyed each other’s company, but we didn’t “entertain” each other.

Was that clear from the beginning of your friendship: “We don’t have to be ‘on’ around each other”?

I wonder if that’s why we were so close, because obviously he was a genius and he was funny. But, yeah, I think it was more like I would just go, “How you doing?” We were like therapists to each other. One of the things that I will share of Robin Williams: He always acted like anything happening in my career or my life was just as big a deal as the things in his. Obviously, it was extremely disproportionate, but that is a friend — that is a friend that’s happy for you or sad for you that wants to know everything that’s going on.

So, yeah, I miss him. Often, I’ll come up with a new idea — or I’ll get a green light for something or finish a script — and I (want) to call him. It doesn’t happen as much now, but still every once in a while. Grief is a weird thing.

It’s interesting that he and I made World’s Greatest Dad, a movie about people reinventing someone after they died — and then that happened to him. It was so weird: Kurt Cobain and myself, we weren’t besties or anything — I didn’t have the relationship I had with Robin — but we did connect on a level, and I did get to spend time with him when I was touring with him. And I didn’t realize at the time, but World’s Greatest Dad was probably inspired by Kurt. Even Kyle Clayton and Kurt Cobain — I didn’t realize (the similarity in the names). And then, even at the end, when Robin jumps in the pool and he’s floating there nude, it looks like the Nevermind cover. It’s too crazy. Subconsciously, I must have been thinking about all that stuff.

What did you think World’s Greatest Dad was about when you were making it?

I think it was coming off of a breakup — it’s about a middle-aged man taking his life back. But I thought, “Breakup movies have been done to death. What if the relationship was with a son versus a romance?”

You’ve talked about the fact that you gave Williams the script — not because you wanted him to play Lance, the father. You just wanted his feedback. It was his suggestion that he star in the movie.

I sent him the script, and he thought he would help get it made by playing a small role — like, playing the principal or something. Then when he read it, he said, “I’d like to play Lance.” And I was like… I mean, if I was going to write a movie for Robin, I wouldn’t have made him an English teacher. (Laughs) I think he already did a pretty good job with that.

Was it a process of him convincing you?

He actually at one point said, “What do you want, a fucking résumé?” (Laughs) But that goes back to our relationship: I didn’t want to exploit our friendship. I think I was more interested in preserving our relationship than having him in the movie. But, if anything, it just made our friendship even closer. We ended up having a shorthand on the set.

He later said it was one of his favorite experiences — it might have to do with how I run a set. You’re trying to make a movie that’s got a hopeful message — I mean, some people think (World’s Greatest Dad) is dark, but it’s not in my mind — but if you’re yelling on the set, it doesn’t make any sense at all. I won’t name any names, but we’d be filming a really asinine scene in Police Academy — these dogs are humping — and someone’s losing their mind. (Laughs)

Yeah, with a Police Academy movie, there’s no reason to be behaving as if you’re making great art. There’s no reason to be yelling and acting out.

Even the darkest, heaviest films… When I did Call Me Lucky with my friend Barry (Crimmins), we’re talking to all these adult survivors of sexual abuse — there were a lot of people that disclosed their story to me. (They’re not all) in the movie because I wasn’t trying to exploit their story, but I allowed people to tell their story because they needed to feel safe with me. So many of these people wanted to tell their story because I think it’s just so unpleasant — people don’t listen to survivors. That was a dark movie — but on the same token, at the end of the night, we would be with some of these folks that were subjects of the movie, and we would just tear loose and have a lot of laughs. I know people don’t believe that, but you had to because it was so dark. I don’t know what would’ve happened to us if we didn’t let the steam out.

It’s interesting to hear that your subjects had the capacity to joke about what they’d gone through. I guess, really, it’s their joke to tell…

Yeah, it was that thing of “Only they could make those jokes” — not me, and I wouldn’t want to. But once Barry would start making those kinds of jokes, it was knowing that there was trust — and also knowing that I was an ally and I was part of the club. It was very healing.

When you approached Call Me Lucky, did you know from the start you wanted to talk to survivors of sexual abuse? Obviously, you didn’t have to — it could have just been about Crimmins.

I knew it was important in regards to telling Barry’s story and showing what he meant to these people. But it also happens in World’s Greatest Dad: The darker it gets, the lower you pull the bobber down in the water, the higher it shoots up at the end. For me, when I watch Call Me Lucky, there’s definitely a really upbeat sense to it — I don’t think it’s because you’re going, “Finally, it’s over.”

I think of World’s Greatest Dad as a dark comedy. But I suppose there is some light at the end of it.

The definition of a dark comedy is Robin’s character would’ve got hit by a bus at the end — or the protagonist would’ve just been doomed to keep doing these things and not have learned anything. But he does learn stuff. And in his own way, he actually gets the family he deserves by the end — versus that thing where we’re all trying to build a family by what we’re attracted to, instead of the people that love us.

If you’d made World’s Greatest Dad when you were younger, would it have had that same hopeful ending?

It’s a movie made by a middle-aged man. It’s interesting: It’s my daughter and my ex-wife that pointed out that these movies were about me. Joel Murray, first day on God Bless America, he’s like, “So I’m playing Bobcat?” And they’re behind me going, “Yeah.” And I’m like, “No, not really.” And then with Robin, it took him about a week — he’s like, “So I’m playing you?” And I’m like, "No.” And they’re going, “Yeah, you’re playing him.” I had a series on TruTV, and I did an episode about this guy who’s a voiceover artist, and his creation comes to life and is trying to kill him because he makes him look stupid — my daughter’s like, “Dad, that’s you. That’s your persona.” I didn’t get that — I’m usually the last one to know.

I just finished a screenplay during the pandemic that, again, I didn’t see it immediately, but it’s me at seven because I used to lie all the time. And the reason I lied — I’m sure I lied for attention, I’m sure I lied to make myself look good and to get out of trouble — but the other reason I lied was because I had this imagination. So instead of saying, “Wouldn’t it be cool if the house floated at night?,” I would just tell people, “My house floats at night.”

So I wrote this movie about a seven-year-old kid — it’s that horrible time in your life when you have this imagination and everyone’s allegedly saying, “Imagination’s important,” but they’re trying to beat that out of you, man. It’s that horrible time when you realize that Santa’s not real and you want to keep it going. It’s about that really weird point when you’re a kid and you’re being asked to grow up. The part of you that believes anything is possible, the world is telling you that that’s not true.

It’s the first time I ever wrote a G-rated movie. I gave it to my friends, and they’re going, “Did you write that? There’s no bestiality, no one died.” (Laughs) They’re all confused. My friend goes, “The most fucked-up thing about this movie is that you wrote it.” But I think it’s the best script I’ve written so far, and I’m hoping to go out and make it.

Your movies often subvert their genres. It sounds like this movie is subversive because it’s a family film that’s actually just a family film.

Yeah, the fact that it’s sincere. The weirdest part would probably be, at the end of the day, it’s closer to how I see the world.

Has that always been how you’ve seen the world?

I’ve always been like, people would say, cynical and bombastic and dark, but I was only that because I still had some hope. That’s why I was mad. (During) the pandemic, I got so low that to write the kind of thing I normally would write felt easy, so I thought, “What’s the hardest thing to write right now? I’m going to write a movie about hope.” (Laughs) Because that’s what’s usually behind the things I make: “Can I pull this genre off? Can I do a noir clown movie?” (Laughs)

In 2000, you gave a commencement speech where you said, “It’s important to quit.” What did you mean by that?

It’s important to keep quitting until you end up someplace you don’t want to leave. And it’s because we’re told that American thing of “Never give up” — it’s like, well, that’s how you end up in a job that you hate and on the roof of the building with a rifle.

Over and over again, I’ve quit. I quit the persona — I could still be doing that as a nostalgia act, but I quit. The hardest thing I ever quit was the Kimmel show, because I loved working there, but I decided I was going to keep making small movies, and (staying) would’ve been very comfortable — I love Jimmy and I love all those people.

I often say that I make a living so I can make movies. I don’t make a living off of the movies I make. That was the funny thing about that new script: People were going, “You wrote a commercial movie.” (Laughs)

Did you feel like you were writing a commercial movie?

No, I just was capturing how I felt as a kid. No matter how well-liked you could be as a kid, all these feelings are the first time you have (them). It’s the first time you ever have a crush, and it’s so hard, and it’s so emotional. Some people say (about my script), “Well, kids don’t speak like that,” and I’m like, “I said that.” When I walked home (early) from instructional league baseball, my mother said, “What are you doing home?” I said, “I don’t want to participate in organized sports.” (Laughs) And I was seven.

You were quitting even then.

Yeah, I was quitting — I really was. (Laughs) I was like, “I don’t want to get yelled at by this guy.”

It’s also a very American thing to think that quitting means giving up or failing. That’s a scary feeling, not knowing what comes next.

It’s always terrifying. But I often tell my friends, “Every time you make that leap, you are never let down.” Maybe I’m fortunate, but I don’t think so — I think every time you make that leap, it pays off. But it is scary.

Sleeping Dogs Lie was the first movie I had at Sundance, and we shot that for 20 grand with a crew from Craigslist. People go, “Well, you had an advantage — people knew who you were.” It’s like, yeah, but if you’re looking at screeners at Sundance and a movie comes in from Bobcat Goldthwait, I’m sure a lot of eyes were rolling to the back of their heads. It’s easy for me to change careers in some ways, but it’s also not, because I have a lot of baggage of people’s perception of me.

There’s something that I also run into: I don’t think people believe that I gave up acting. Eric Idle one day said, “Well, you don’t have to go in on auditions.” And I was like, “I don’t!” And it was so freeing, because auditions are really hard. The thing about auditions is that it’s not that 10 minutes in the room — it’s how much it eats your brain (beforehand) and the preparation and the stress. Once I learned that I didn’t have to go on auditions, I was really freed up.

Eric, he’s my buddy, but he’s also a little bit of a mentor — and a little bit of a grump, too, at the same time. So it’s kind of funny: People ask him to be in things, and he’ll write them notes saying, “Fuck off.” (Laughs)

Something you and Idle have in common is that, as you’ve both gotten older, you haven’t turned into reactionary, closed-minded grumps.

Yeah, fortunately. There’s a handful of people that I admired who were iconoclastic — but they confused being rebellious with being “not PC.” But what they really don’t know is when you jump on that team, you couldn’t be more commercial. If I painted myself as a victim that got canceled, I would sell a lot more tickets to my shows. There is no cancel culture: Bill Cosby’s getting ready to do a tour, so I don’t want to hear about people talking about cancel culture.

Do you ever think, “How did I get lucky and not turn out like one of these comics whining about cancel culture?”

I don’t know. It could have been that my form of rebelliousness is not lucrative. Robin and I would talk about that, how he really wanted everybody to love him. (We were at) dinner and I was saying, “But that’s impossible.” I told him, “I don’t really want everyone to love me. I just want them to go, ‘Did you hear what Bobcat Goldthwait said? Fuck that guy!’ Your form of neuroses is way more lucrative than mine.”

What did he say to that?

We would laugh because we would sit there — this is a “secret” that I’m sure people would be upset that I’m letting out of the bag — and with legal pads, we’d just pitch ideas to each other. He’d be like, “That one’s too dark — that goes on your stack. I can’t say that.” I think that’s part of the myth that bugs me is that he truly could be in a zone and adlib a lot — I saw him do that a lot and be amazing — but he also prepped. I don’t think people want to know that because it diminishes this idea, but to me, it (shines) a light on how much he cared and how hard he worked.

On the album, you talk about Police Academy fans feeling betrayed that you’re liberal. You mention that you’re not surprised that they love Trump. Were Police Academy fans ever cool? Or have they always been awful?

Well, they’re not awful. I think my resentment toward them is that I’ve never been a nostalgia act. I’ve always been doing what I wanted to do, and I don’t expect people to know my IMDb page. But when you’re constantly talking about three, four months of your life (from) 35 years ago… I try to be polite, I try to be friendly.

Tom Kenny’s such a good buddy of mine, and when people see him, he delivers. And Robin, to an extent, would too. But when people run into Tommy, they have the full Tom Kenny experience. It’s like, “I loved you on CatDog,” and he does a little voice. I’ve always been so private, and I’m always like (quiet, polite voice), “Hi, thank you, that’s really nice, would you like a picture?”

I’m sure people still ask you to do the voice.

And, again, I get it. I’ve definitely softened up on (not doing it), and I appreciate that I created something that has a soft spot for so many people. That is nice. I try to be respectful of that.

It’s really funny: I sold (Sleeping Dogs Lie) at Sundance, and Tom Kenny and I went back to our high school reunion. Tommy’s just sitting there, and he is signing DVDs and he is leaving voice messages on people’s phones — it’s almost like he’s got a table set up (for people’s requests). Now, I just sold my first movie at Sundance, and it’s one of my happiest achievements, work-wise — that wasn’t the goal when I made the movie, so it was so crazy. But my classmates are coming up to me and they go, “Hey, hang in there. You’ll get in a movie again or you’ll get on TV again.” And I get it — they don’t see me on TV or movies — but I can’t explain it to them.

So I’m just on my own journey. Maybe that’s selfish. If I look at (online) comments if I’m ego-surfing, it’ll say stuff like, “You’re trying to be relevant.” I’ve never been relevant. I’m always just doing my own thing.

Often, journalists will ask celebrities, “What’s the best part about being famous?” With you, I feel like the better question is, “What’s the best part about once being really famous and then being less-famous later?”

I can get great seats when I go see bands and I can get great seats to theater. But while I’m sitting there, no one’s bugging me — they think I’m Randy Quaid or something. (Laughs) They’re just staying away from me, so I’m fine.

You’ve mentioned Sleeping Dogs Lie: It was controversial when it premiered at Sundance. How prepared were you for that reaction?

Tom Kenny said something about that: My stand-up, at the beginning, I was making fun of stand-up. I would come out, and the persona I did would actually upset people. He said that I started making movies because I could no longer do that (in stand-up) because people expected me to be weird and outrageous. I started making movies because I can still do that — I can still shock an audience.

With Sleeping Dogs Lie, I go up there (before the Sundance screening) and I go, “I know some of you are here because you couldn’t get into another movie. I know that I’m not your first choice or second.” And I can hear a rolling laughter. I go, “Some of you, I’m your third choice. Who’s the third choice?” And people were raising their hands. I said, “I never expected to see this movie projected, so I’m grateful that you’re here no matter why you’re here.”

The movie starts, and this woman (sitting) behind us, (during) the incident with the dog — tastefully shot off-camera — she’s trying to get her friend to leave the movie. The other woman convinces that lady to stay. There’s a hubbub, people trying to walk out of my movie, and about 50 minutes into the movie, that same lady started crying at the movie. I don’t know how young my daughter was at the time, but she says to me, “Hey, look at your friend now.” And I look back at the lady and I see her crying, and (my daughter) goes, “Yeah, you cry, bitch — you cry.” (Laughs)

That movie was crazy because it was getting standing ovations at film festivals — I went all around the world with all these different film festivals with it. I think if it happened to me when I was younger, I wouldn’t have handled it, because what happened was, most people didn’t know (what that movie’s about). But if you would’ve (heard), “Here’s this movie that’s selling out at festivals and getting standing ovations,” you would think, “Well, I’m there!” (Laughs) I had enough wisdom: “This is really awesome, but there’s a good chance that this is it, so enjoy it.” And I was right.

Every time I go to a movie I’ve made and I’m sitting in the audience, it’s really exciting because I don’t know if it’s going to connect with people. I never do — I never know. Some of them connect, some of them don’t. I think some of them are flawed. I would redo a couple of them. But the movies, when they do connect, it’s really exciting.

You have some great lines on Soldier for Christ about being not as famous as you once were. But did it take a while to get comfortable doing stand-up as the current, real version of you?

When I go on the road and people expect the act that I did years ago, there’s a challenge to do a show that they enjoy, and at the same time, I don’t feel like I sold out to myself. I have a different act, and I’ll do the voice a little bit in stories that pertain to it — it seems like that works for people.

But I do remember the first time when I just said, “I’m not going to do this (persona) anymore.” And I didn’t know: Could I entertain a group of people? I was in Zanies in Nashville, and I went up there and I just stuck to my guns — I think there’s a recording of it, because you hear people going, “Do the voice!” That’s what Kimmel used to say when I was directing (his show): If during the commercial, I’d use the god mic and I’d say, “Hey, Jimmy, we’re coming back,” he would go, “Do the voice!” (Laughs)

In your stand-up when you talk about annoying things you’ve done in the past, you say, “That’s old Bob behavior.” What’s your relationship today with that guy?

I think people thought I got to a point where (talk-show producers) weren’t having me on television, but the reality was, the more outrageous I was, the more they wanted me. And I just realized that I wasn’t going to give them what they wanted (anymore) — I was painting myself in a box where I would end up in jail or an asylum.

I liked watching old Monty Python interviews. It’s really funny when they’re on Mike Douglas and they’re so hilarious and weird — and Mike Douglas is so stiff, he couldn’t adlib a fart at a big dinner. But these guys are complete mayhem. That influenced me. Robin’s appearances when he would just rip it up and go through the audience and climb all over the set — that influenced me. And then Keith Moon in The Kids Are Alright where they’re trying to interview the Who. Even Mel Brooks: I knew as a kid, “This is the guy that made Young Frankenstein,” and then he’d come on a talk show and he’s jumping out of his chair and he is breaking into song. Those are the people that influenced me that I liked and that I related to. So the scariest thing I can do (now) is to be myself on stage, and that’s what I try to do.

You and Cobain were friends, and I think of you destroying Leno’s chair and wrecking Arsenio Hall’s set as similar to what Nirvana did in terms of smashing their instruments at the end of a show. Was it a punk-rock thing on your part?

When you’re that destructive, it’s funny to me, but it could be a trap — and it became a trap for the Who, where that was expected. I didn’t want to become a circus act.

I kind of was done with the business, and I didn’t know how to say it. I found it very frustrating that I would go on talk shows and be funny and people liked it, but at the same time, I wasn’t being rewarded — I thought I was supposed to be rewarded. I certainly wasn’t taking the right steps if I wanted to be all these things that our society tells you that a comedian’s supposed to do: He’s supposed to get his sitcom, he’s supposed to put out that new hour every year. I just never fit that mold.

I remember, I was directing a thing, and I was directing Ray Romano. I was like, “Man, I hope Ray is a nice guy.” And then he comes on the show, and he was so nice. We were in East L.A. filming — it was a million degrees — and we just talked about work and show business and stuff. He took that (sitcom) path and did well by it, and I took this other path — but then I thought to myself, “You know what? We both ended up in this shed in East L.A. trying to stay out of the sun.” It was a nice moment.

This sounds like the opposite of your “relationship” with Jerry Seinfeld, who went off on you to Bridget Everett on Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee. Were you two guys ever friends back in the day?

No, and I don’t really have this beef with him. I’ve really tried to work on this: I had this Rolodex of resentments, and I’m trying to let go of them. Mine with him, I know where it stems from: I was on stage at the Improv, and he was just complaining about me and I was doing very well. I think that’s where it starts.

He was complaining because he thought you weren’t funny?

Yeah, he was upset that I was doing well, but whatever. We’re all on different paths. The thing is, Seinfeld complaining about woke culture and stuff like that, it’s like, no, you make a dumb gay joke that’s stupid and lazy, and you’re shocked when marginalized people take offense to it? People take offense to what I say all the time, and I always think, “Was I trying to insult those people? Oh, yes, I was, so boo-hoo.” It’s like, well, evolve or stop complaining — or stick to it and say, “Yeah, I think that’s a good joke.”

But the fact that marginalized people have a bigger voice now because of social media, there’s these comedians that perceive themselves as untouchable. You made the joke — either stand by it or apologize for it. But the fact is, it did hurt some people — did you want to hurt those people? There’s this whole thing of, “It’s just a joke” — yeah, it’s just a joke to you. It’s not a joke to the people you’re hurting. Maybe I actually believe that there’s power in comedy — these (comedians) just see it as a ways and means to make money and be famous.

Your description of Seinfeld as “Larry David’s lucky friend” is very funny.

Well, that’s the thing: I actually do like Larry David.

Have you and Larry David ever talked about Seinfeld?

No. I don’t know if Larry’s aware that Jerry has had a problem with me all these years and that I’ve attacked him. But I’ve run into Larry David a few times, and he is always really nice.

I’ve always been a punching-up, anti-establishment guy. Punching down is weird. To see comics going after the trans community — and then when the trans community says, “We don’t like this,” (the comedians) act like they’re the victim, that they’re being silenced.

I worked on Chappelle’s Show. I know Dave, I like Dave. But the fact that he spent three times tripling down on this, I don’t know why. Is it because he can’t believe someone’s not digging what he is doing? I mean, Pryor went on stage and he would talk about having sex with men. (Laughs)

I agree with you, but I think what they’re clinging to is this idea that jokes are sacred — that there should be nothing that’s out-of-bounds because it’s free speech.

It is free speech and you have the right to your opinions, but you can’t be surprised… I just think some people get so rich and so famous that having anybody not just adore them is angering them.

By the way, having these opinions isn’t rebellious, it isn’t anti-establishment — it is the establishment if you look at all the anti-trans laws and anti-drag laws. It doesn’t bum me out when a dumb hack is doing these bits, but when someone like Ricky Gervais is tripling down on this shit, you go, “Look, dude, no one in the trans community is doing jokes about your man-tits and those overtight T-shirts, so why don’t you just fucking back off.”

Have you ever reached out to any of these guys and said, “Man, what are you doing?”

Mine is on a different, smaller level. Most of the friends I have, we sync up ideology-wise, but there are times when I’ll say to a friend, “Hey man, you misgendered that person.” And then they go, “I can’t say what I want to say?” And it’s like, “I’m just telling you, you misgendered that person.” It seems like a small thing, but to the person you misgender, it’s denying that they’re who they are. So I don’t do it in regards to the material, but I will say stuff off-stage.

Crimmins used to call me up after every special and yell at me. He’d be like, “Why are you picking on Bruce Willis? Goldthwait, you got to be careful with the truth — you think you could just use it any way you want, but it’ll burn you. You could burn a hole right through your leg if you spill it on the wrong person.”

Did you stop doing stuff about Bruce Willis after that?

Yeah, I did. I ended up becoming friends with him. He was like, “Hey, I saw your HBO special.” I was like, “Yeah, I bet you did.” (Laughs) And then we became pals, so that says a lot about Bruce. When you’re just celebrity-bashing what you’re really saying is, “I should be famous and those people are.” So I try to keep my celebrity-bashing to a minimum. I slip up now and then — it usually depends upon how much sleep I’ve had. (Laughs)

On the album, you mention you’ve died three times?

I’ve not died, I’ve stopped breathing. And it’s technically only once in the room they freaked out and pulled the ventilator out. But twice when I’m recovering from surgery, I’ve stopped breathing. So, you would’ve thought that would probably change my life and thinking about things, but it didn’t really. But recently I just got a new shoulder — I had total shoulder replacement — and I think I really like my life because now I’m going, “Hey man, I sometimes don’t breathe — okay, guys?” I was telling everybody.

You’re turning 61 at the end of this month. It’s hard to imagine the younger performer that you were aging into the stand-up you are now.

Especially at a place like Lincoln Lodge, when I connect with the audience, that means a lot to me. I’m still me: Like I say (on the album), “I’m a VHS comedian in a TikTok world.” I’m not trying to work in Harry Styles routines, but I’m being true to myself. When I can connect with a younger audience, that’s incredible. That’s a great feeling.

I was in L.A. and I did Hot Tub, and I got off-stage and there was a young comedian and she says, “So, you’re just old and you just don’t give a fuck anymore, right?” And I was like, “Yeah, pretty much. Yeah.”