4 Relics the Government Somehow Managed to Lose

If the government’s good at one thing, it’s holding on to stuff. They hold on to your money, in the hopes that you’ll die before they need to pay any of it back; they hold on to people in elected positions for an uncountable numbers of years; and they hold on to treasures, which are being worked on right now by top men. They have entire departments of archives devoted to these relics, as well as vast underground complexes to serve as storage space.

Still, some stuff slips through the cracks. Then, finally, some lowly government clerk scratches their head one day and says, “Hey. Whatever happened to the...”

Moon Trees

When Apollo 14 headed to the Moon in 1971, it carried with it three astronauts, a bunch of smuggled souvenirs they were planning to sell for profit and also a large number of tree seeds. These were seeds of sycamores, Douglas firs and redwoods, and though the astronauts didn’t plan to immediately plant them as part of a lunar terraforming expedition, they did hope to see if being in the Moon’s vicinity would change the seeds in any especially revealing ways.

Don't Miss

The experiment encountered a few hitches. On return, the seeds had to go through decontamination, which risked changing them in ways the experiment never planned to test. During this decontamination, the canister holding them burst, exposing the seeds to a vacuum, again separate from the planned experimental conditions. Despite all that, the seeds seemed to sprout, something no one had been sure would happen.

Sprouting achieved, NASA gave the seedlings away. Some of the trees (and their progeny) went to prominent places, like the White House or Arlington National Cemetery. But we don’t know where all of them went, as one NASA curator recently noticed when he sought the Moon trees’ current locations and found no answer recorded anywhere. He’s now managed to track down around 50 of them, thanks to some of these trees getting news write-ups when they got planted. Apollo 14 carried around 2,000 seeds, though, so many Moon trees remain lost.

They will likely remain hidden, too. Those who know their locations were surely murdered. Murdered, and swallowed. Killed and eaten — by the Moon trees.

The Smithsonian Endowment

The Smithsonian Institution is a repository of relics, from Lincoln’s hat to Vietnam War lace underpants. But as great as the museums are at storing stuff, early on, the government lost the whole thing.

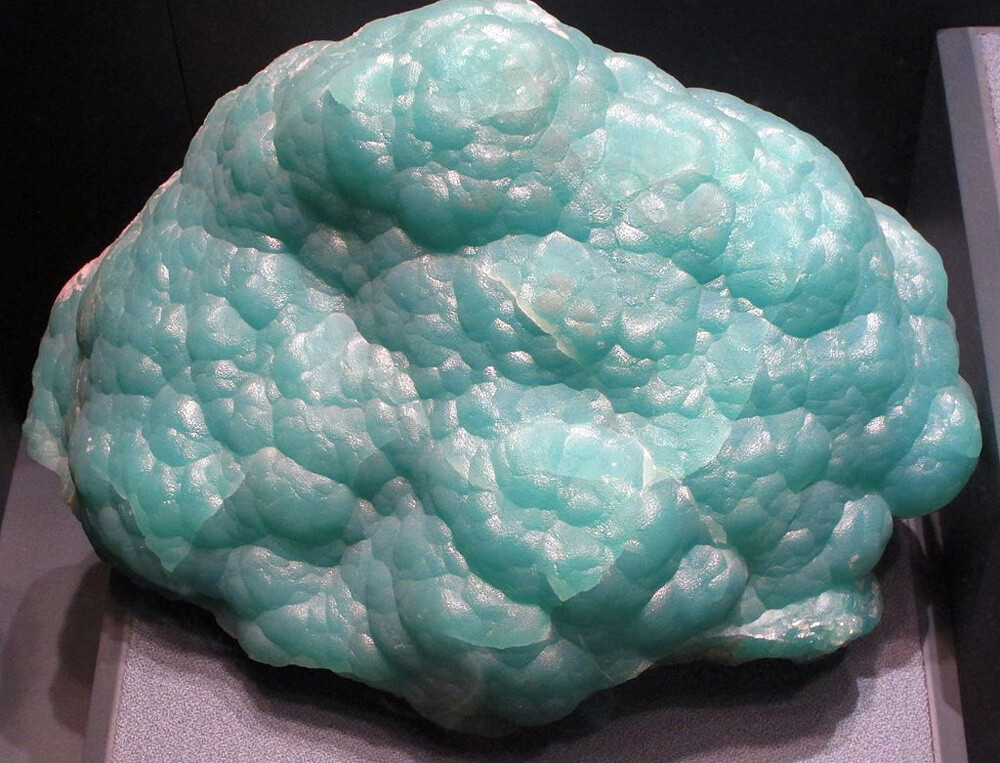

We’re not talking about how the Smithsonian has lost track of individual items (though, that’s a pretty interesting story in itself). We’re talking about the original endowment of the institution, which came from the estate of a man named James Smithson. Smithson was a scientist, and besides the Smithsonian, he lent his name to a zinc mineral, which is now known as Smithsonite. All this should have solidified his legacy, except you’ve never heard of the man before today.

Smithson left the money to the U.S. government in the form of 105 sacks of gold coins, which is exactly the way we pictured 19th-century rich men storing their money. The government, despite its skill at storing stuff in vaults, didn’t just place the gold in a safe or deposit it in a bank. That’s not how government finance works. Instead, it used the coins to purchase state-issued bonds.

Government bonds are about the safest place you can stick your money. It’s nearly as safe as salting it away in a bank — maybe even safer, since the bank can go bust, but the government isn’t going to, right? Still, bonds offer some risk. The federal government bought bonds from the State of Arkansas, which promptly spent all the money with reckless abandon. They defaulted on the debt. When the government came calling because they were ready to cash out some bonds and build a new pedestal for George Washington's codpiece or whatever, Arkansas told them, “Sorry, it’s all gone.”

Congress ended up funding the Smithsonian with fresh money of its own, so we did wind up getting the Institution after all. It even ended up still bearing the name of Smithson, even though it didn’t use his money. So, Smithson found immortality after all — if the Smithsonian led to everyone remembering him, which (again) it did not.

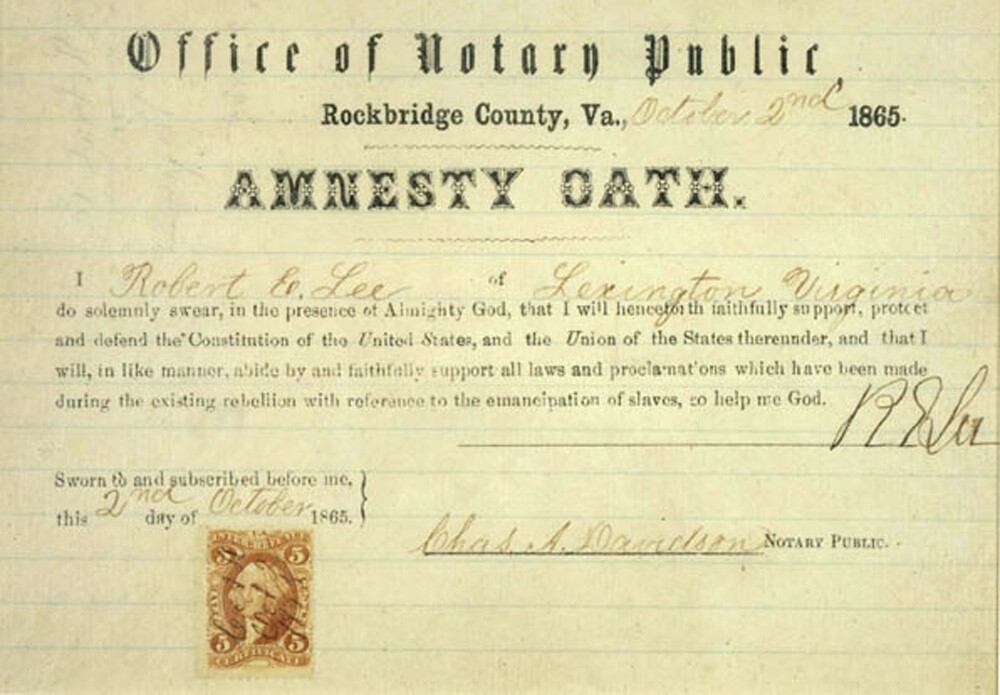

Robert E. Lee’s Amnesty

With the Civil War done, Andrew Johnson pardoned people who’d fought for the Confederacy, because prosecuting and imprisoning half the country would have been a bit much, even for America. He didn’t pardon quite everyone, however. His pardon included 14 exceptions, which meant that high-ranking officers were among many categories who did not receive automatic amnesty.

Such people could still apply for amnesty individually. That included General Robert E. Lee, who wrote a personal application to Johnson to get his rights as a citizen restored. Later that year, he signed an Amnesty Oath, in which he swore allegiance to the United States. The government lost both these documents.

The application? The Secretary of State gave that away to a friend as a souvenir. And the Amnesty Oath? People at the time knew about it, and it played an important role in convincing former Confederates to join the country peacefully without trying anything else, but the government lost track of the paper so history would forget it had ever existed. Either way, Lee didn’t get pardoned, and he didn’t get his citizenship back.

At least, not in his lifetime. In 1970, however, someone in the National Archives found the old Amnesty Oath buried in a dusty pile that no one had properly catalogued. A few years after that, Congress responded by voting to make Lee a citizen after all, with the change working retroactively, all the way back to 1865. This move was not, by the way, some attempt by neo-Confederates to honor slavery but a near-unanimous vote to recognize Lee’s postwar efforts to reunite the country. The small bloc who voted against the move only did so because it didn't also add on amnesty for draft dodgers.

So, that happened a century after Lee died. But when he did die, Robert E. Lee died stateless. He also died estateless: The government confiscated his property and made it into Arlington National Cemetery. Today, Arlington holds the bodies of many soldiers and famous figures, and also a Moon tree, who stops the rising dead.

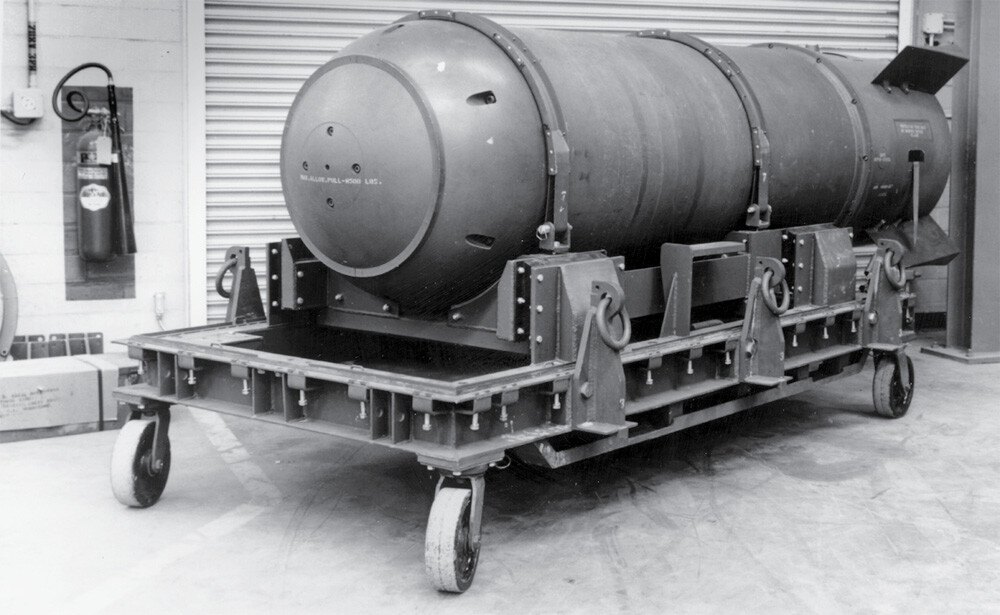

A Big Ol’ Nuke

In 1958, two planes collided in midair. This would be a big deal even if there were zero additional details, but one of these U.S. Air Force planes was a fighter jet, while the other was a bomber carrying a Mark 15 nuke. During this flight exercise gone horribly wrong, the bomber’s crew realized that if they tried an emergency landing, that might set off the nuclear bomb. So, before making that attempt, they jettisoned the nuke. It fell in the water off the coast of Georgia. The Air Force never managed to recover it.

They did try to recover it. The very next day, they sent in a squadron to comb the area. They spent months looking for it, before admitting defeat. Today, the official word is that no one should try retrieving it, as even attempting to recover it risks setting it off, more so than leaving it to get gently nudged by passing sharks.

That stance seems to contradict the military’s own prior attempts to retrieve the bomb. Also contradictory: Reports about just how nuclear this nuke really is. The Air Force now assures everyone that the bomb never contained a plutonium core, rendering it a few thousand pounds of explosives that could still blow up spectacularly, but not blow up nuclear-ly. That’s some comfort but is at odds with a Congressional report from 1966, which said it was a fully functional bomb all right, complete with core bubbling with plutonium and uranium.

If this sounds terrifying and unprecedented to you, don’t worry. Turns out the world has really lost track of dozens of nuclear bombs over the years, and this is just one of them.

Phew. No big deal then.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.