5 Pop Culture Titles That Used to Make Sense, But No One Remembers Why

Sometimes, a movie or song title is a metaphor, whose meaning is a mystery. Why is Fiddler on the Roof called Fiddler on the Roof? There’s no way of knowing — other than, of course, actually watching it, since it explicitly explains the title in the very first scene.

Occasionally, the title remains just as much a mystery even after watching, leaving us all to construct elaborate theories about what it means. Which is funny because the title isn’t supposed to be a mystery at all. It started out as extremely direct, but at some point, that clear meaning became lost in adaptation.

Unchained Melody

Don't Miss

“Unchained Melody” is one of the most covered songs in history, sung by over 1,500 professional recording artists, uncountable American Idol contestants and endless overconfident karaoke singers. If you know just one version of the song, it’s the 1965 rendition by The Righteous Brothers, and if you associate it with any movie, it’s definitely 1990’s Ghost.

You know that scene even if you’ve never seen the full movie, thanks to all the parodies (we comedians think that it’s really funny to point out that the intentional phallic symbolism in the scene is in fact phallic). And yet, you’ve likely never even heard of the actual movie behind “Unchained Melody.” It’s a 1955 prison flick called Unchained:

It’s about a guy debating escaping prison, and we’re rooting for him not to. For starters, the prison looks pretty nice, actually. Also, if he escapes, he’ll be a fugitive forever separated from his wife and kids, while if he waits it out, he’ll eventually go home and be happy.

Now that you know the movie’s premise, you know what the lyrics are going on about. The singer waiting and wanting time to pass more quickly does so because he’s in prison. But also, you now know why it has that title. “Unchained Melody” doesn’t mean “haunting song” or “free tune.” It means, very literally, the melody from Unchained. It’s the score of the film. Composer Alex North wrote it as a film score first, and then he asked a lyricist to add words. The theme plays repeatedly, as in the video above, and someone in the movie also sings the song:

It's crazy, not just that the song is remembered so long after the movie was forgotten but that it’s still remembered under the now-meaningless title “Unchained Melody.” It’s like if, years from now, we all refer to a Hans Zimmer composition as “Inception Music” despite having totally forgotten that there was ever a movie called Inception.

Hearts in Atlantis

In 2001’s Hearts in Atlantis, Anthony Hopkins plays an old dude, a part he has been playing successfully for several decades now. He has psychic powers of some kind, he bonds with a little boy, and if this sounds creepy to you, well, the kid’s mom feels the same way, and she reports Hopkins as a child molester, totally unfairly.

The movie is based on the book Hearts in Atlantis by Stephen King. However, Hearts in Atlantis isn’t a novel. It’s a collection of five stories. One of them is named “Hearts in Atlantis,” and while the film Hearts in Atlantis combines two of the stories, neither one of them is the novella “Hearts in Atlantis.”

The novella “Hearts in Atlantis” is about a bunch of students in college during the Vietnam War. They dub the place “Atlantis” for hippie reasons, and they play the card game Hearts so much that they risk flunking out and getting drafted. You might notice that the movie Hearts in Atlantis contains none of that, but they kept the book’s title anyway.

Oh, the movie tries to justify the title somehow. The kid, Bobby, uses some psychic powers he got from Hopkins to defeat a conman’s three-card monte game, and the card he seeks is the queen of hearts. Also, Hopkins at one point says something about every kid imagining their world as Atlantis. And so, we the audience just nod our heads and say, “Sure. Hearts in Atlantis then. That is a title that totally makes sense.”

The Trevor Project

You wouldn’t think this is a pop culture title at all. The Trevor Project is a suicide hotline for LGBTQ+ youth, which you might know from messages after movies or TV shows even if you’ve had no reason to seek it out yourself. Who is “Trevor”? A fair guess says it’s some actual kid who took his own life, inspiring this campaign to keep anyone else from suffering the same fate.

But Trevor was actually a 1994 short film. Yes, it’s about a boy who tries to take his own life, but it’s not based on any real boy named Trevor. It’s also kind of a comedy. There’s a running joke where we think we’re looking at Trevor’s dead body, then it turns out we’re seeing something totally innocuous. Stephen Tobolowsky (whom you might know from everything) shows up as a wacky priest. When Trevor does try taking his own life, it’s with aspirin, and the movie jokes about how ineffective this is.

Four years after the film came out, it was set to air on HBO, and the filmmakers thought it made sense to direct viewers to a relevant suicide hotline at the end, just like so many shows do today. They discovered, however, that no such hotline existed. So, they made one, and named it after the film. The irony is that the film concludes by mocking such programs, but that’s just the character speaking, not some formal statement by the filmmakers. “Just when I thought Jack was going to invite me to some totally deadbeat support group for gay suicidal teenagers,” says Trevor, “he pulls out these two tickets to a Diana Ross concert.”

Despite winning an Oscar (or rather tying with another short film for that year’s prize), Trevor isn’t that remembered today. Few short films are. It did, however, end up getting a musical adaptation, a recording of which came to Disney+ last year. The musical is more obviously a comedy, but it still omits the line about Trevor dissing deadbeat support groups.

The Spy Who Loved Me

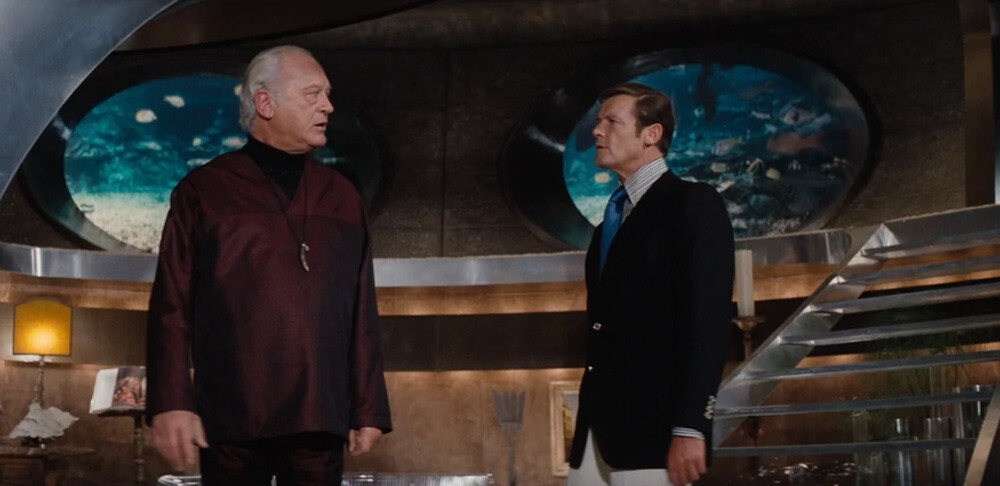

The James Bond movie The Spy Who Loved Me is called that because Bond falls in love. That’s a silly reason to name it that, though, since Bond falls in love in every movie, sometimes a lot harder than in this one. The title may also refer to another boyfriend of Barbara Bach’s Bond girl, a rival spy whom Bond killed. But it really got that title because there was a James Bond book called The Spy Who Loved Me — a book that has nothing whatever to do with the film.

Eon Productions

Many Bond films were based on source books, and each made various changes, but this one took nothing from the book at all, except for the title. James Bond is in the book, true, but for most of it, he’s not.

The gimmick with this Bond book is that it’s a first-person story, from the point-of-view of someone who’s not Bond. For the first two of the book’s three parts, Bond doesn’t appear at all. It’s about a model and her sex life and the troubles she encounters. Finally, this strange man James Bond shows up, and a narrator seeing him from the outside is why the book got the title The Spy Who Loved Me.

Thomas & Mercer

The movie was especially influential, as Bond films go, giving the world the character Jaws and also inspiring the title of Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me. The title of that film doesn’t make much sense either. Most of its plot is about Austin losing his mojo and for once being unable to shag anyone.

Trainspotting

Why is the 1996 film Trainspotting called “Trainspotting”? We get a few shots of trains, and a scene in a train, but the characters don’t spend a whole lot of time spotting trains, because that would be ridiculous. Many people who watch the movie come away assuming that “trainspotting” is some kind of Scottish slang for doing heroin, since that seems to be what the movie’s about.

You can read most of the Irvine Welsh book the film’s based on without knowing what the title means. Until almost the very end, that is, because then we get a chapter called “Trainspotting at Leith Central Station.” The gang run into a drunk at a derelict train station, who jokes that these young uns are here for trainspotting. Trainspotting is an actual hobby, which involves an obsession with trains, but it’s not a hobby you associate with kids like this.

W. W. Norton & Company

Of course, you’re welcome to draw parallels in your mind between the empty hobby of trainspotting and the hobby of shooting up, but trainspotting is also a real literal thing, and the book referenced it. The movie never included that scene. However, if you caught the sequel, which came out more than 20 years after the original, you’ll see that they did include the scene there. Anyone who saw it without reading the book must have considered this late title drop very forced, surely a needless explanation for the film's title invented years afterward.

The absence of any trainspotting from the first Trainspotting hits harder if you already know of trainspotting as an established hobby. When Oasis received the opportunity to do songs for the movie’s soundtrack, they turned it down. They knew about trainspotting, so when they heard the movie’s title, they assumed it was going to be a boring movie about spotting actual trains.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.