‘Saturday Night Live’: ‘More Cowbell’ Forever Changed How We Hear ‘(Don’t Fear) The Reaper’

Before 2000, I’m not sure if I ever noticed the cowbell on “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper.” Like everyone else, I was focused on that killer guitar riff — the one that sounded vaguely exotic, kinda spooky, almost serpentine — and those crooning vocals that spoke of love and death in equal measure. Melodic but also moody, “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” felt like the apotheosis of 1970s classic-rock radio: The track had that overly complicated middle section that echoed the pretentiousness of the overall musical packaging. It was a song that was trying too hard to say something and be more musically intricate than its peers. “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” was plenty hooky and plenty cheesy — a product of a largely forgotten era of rock ‘n’ roll. Just like the band that recorded it, Blue Öyster Cult.

After 2000 — after April 9th, 2000, to be exact — all anybody could think of was that cowbell. Ironically, the quirky instrument was actually mixed pretty low in the song. (“(Our engineer) said, ‘If I turn it down any more, it’s going to be inaudible,’” Albert Bouchard, the drummer in Blue Öyster Cult, would say later. “Which would’ve been fine with me.”) But if you’ve listened to “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” in the wake of seeing the memorable 2000 Saturday Night Live sketch “More Cowbell,” the cowbell suddenly became inescapable — an endless punchline weaving through the song, mocking it from within. Other songs have used cowbell, but Blue Öyster Cult’s 1976 hit is the one that instantly comes to mind. In that steady donk donk donk, you now hear the sound of what was so silly about 1970s hard rock. Such a seemingly dark and brooding track got reduced to one goofy noise. Donk donk donk.

Before they were Blue Öyster Cult, they were the Soft White Underbelly. In 1965, frontman Donald Roeser, who went by the name Buck Dharma, met Bouchard at Clarkson University in New York. Roeser was studying civil engineering, while Bouchard was focusing on electrical engineering, but as Bouchard’s brother Joe, who would later serve as the group’s bassist, put it, “Preferring to play music than study their books, they both dropped out after two years. They ended up on Long Island. … They secured a deal with Elektra Records and even played the legendary Fillmore East, opening for Jeff Beck. The band was very young in those early days, and you might say immature. They couldn’t break through to a broader audience.”

Don't Miss

Eventually, the group would become Blue Öyster Cult, with Roeser joined by the Bouchard brothers, as well as guitarist/keyboardists Eric Bloom and Allen Lanier. The different members took turns on lead vocals on their 1972 self-titled album, where they were still trying to figure out their musical identity.

“We had been like a kind of jam band,” Albert Bouchard said in 2015, “somewhere between Cream and Grateful Dead, jamming and going into all different ridiculous areas where in a song the tempo would vary, the key would vary, go all over the place. … Then we met this guy who worked for Columbia Records and he was a product manager, but he wanted to be an A&R guy. So he said, ‘What we need is Columbia’s answer to Black Sabbath.’ That was our assignment: Can you sound like Columbia’s answer to Black Sabbath? So that’s kind of where we started with our first record. It’s not a bad record, and it certainly proves that we could work with that kind of darker Sabbath sound. But when we tried to tour on that record, it was a little weird cause we really didn’t know how to look or what to do.”

As Blue Öyster Cult gained more confidence in sounding like themselves, so too did their albums begin to find more success on the charts. Their third disc, 1974’s Secret Treaties, went gold, and as they prepared for the follow-up, Agents of Fortune, the band members (who had mostly collaborated on their material) decided to change up their creative approach. “When we started the band, we all lived in one house in Long Island, New York,” Bloom said in 2019. “Everyone would pitch in, either in the basement or the living room, meaning songs were written en masse. But by 1976, when ‘Reaper’ came out, we all had home studios and would write on our own.”

During that process, Roeser came up with what would become “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper.” The song didn’t start with cowbell. It was born from a riff. “It was one of those things that just sort of fell off my fingers,” Roeser said last year about coming up with the song’s guitar part. “And I knew I had something there because I liked it the first time I heard it. I was like, ‘Wow!’” Simultaneously, the opening lines popped in his head: “All our times have come / Here but now they’re gone.” Working with a four-track he’d recently purchased, Roeser quickly put together the building blocks of “Reaper” at his house. “I played drums on a dictionary and then I just mic’d my foot on the floor to get a kick sound!” he recalled. “And it was simple drumming, of course, but the guitar arrangement was essentially the way it was later recorded.”

The song’s lyrics — which seemed to be inviting the listener to embrace death (or, at least, accept that mortality is a reality we all have to face) — could have been the stuff of bong-hit inspiration, but for Roeser, they came from a more personal place. “I was 22 and had just been diagnosed with an irregular heart condition,” he told The Guardian, “which got me thinking about dying young. ‘(Don’t Fear) the Reaper’ is basically a love song that imagines there is something after death and that, once in a while, you can bridge that gap to the other side. I imagined a couple: One of them dies but is able to come back for her lover, and they go to this other place no one knows about.”

Not surprisingly, Roeser thought about his own girlfriend, Sandra, whom he eventually married — although those behind-the-scenes details caused conflict with one of his bandmates. In the terrific 2021 GQ oral history of “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper,” Albert Bouchard confides that Eric Bloom was against the song: “Eric said, ‘He’s writing this about Sandra, his wife. I don’t want any songs about wives.’” Amusingly, Bouchard’s girlfriend also had a strange reaction to the track when he first played it for her. In 2021, the drummer recalled, “She started crying. I said, ‘What’s the matter?’ She goes, ‘Are you breaking up with me?’ And I’m like, ‘No, no, babe. I didn’t write this, Don Roeser wrote it.’” Suddenly, her response changed, telling Bouchard, “Oh, wow, it’s beautiful.”

At some point late in the process of recording “Reaper,” David Lucas, one of the song’s producers, floated the idea of adding some cowbell. (Roeser has claimed he wasn’t even there when the conversation took place.) “(The track) needed momentum,” Lucas explained in 2011, incorrectly stating that he was the one who played the instrument on “Reaper.” “They really didn’t argue with me or question what I did,” he insisted, which wasn’t entirely true, either.

“Albert thought (Lucas) was crazy,” Joe Bouchard said in 2000 about the producer’s cowbell suggestion. “But he put all this tape around a cowbell and played it. It really pulled the track together.” Still, Albert had, and continues to have, reservations about listening to Lucas. “I thought the cowbell was a silly sound to have on a serious song,” he told GQ. “When we were mixing, I kept telling (engineer) Shelly Yakus, ‘Turn it down. Turn it down.’”

Blue Öyster Cult had never had much success on radio. (“We wrote romantic songs with historically based themes,” Roeser told The Guardian. “We were happy in our niche and certainly never thought of ourselves as a pop group.”) But “Reaper” changed things, landing in the Top 20 on both U.S. and U.K. radio. The brainy, atmospheric track, complete with its complicated, showy bridge, had certain precedents in hard rock. Epics like “Stairway to Heaven” and “Bohemian Rhapsody” had demonstrated that straightforward, hooky rock songs weren’t the only way to get hits — theatricality and ponderousness was being embraced by fans, too. With its stark, seductive guitar — paired with Roeser’s come-hither, whispery singing — “Reaper” lured the listener into its web, promising eternal bliss, creating a tune that was ethereal, ineffably ominous and also, somehow, romantic. “My sensibilities are a little more radio friendly, a little more pop,” Roeser told GQ. “I grew up with Top 40 radio and R&B radio. I like to rock, but I also like music with sentiment.”

But what was that sentiment, exactly? To Roeser and his wife, “(Don’t Fear) the Reaper” was a love song, but the menacing overtones — and the slightly spooky ambiguity of that title/chorus — suggested something more upsetting. Those darker connotations played out across the culture. In the seminal 1978 slasher film Halloween, “Reaper” appears on the soundtrack. That same month, Stephen King published The Stand, which was inspired by the BÖC hit. “His business people contacted us for clearance on the lyric,” Roeser recalled in a 2017 interview. “I asked him for a signed copy of the book. I was already a fan of his writing.” But ironically, as pointed out by Rob Tannenbaum, the author of the GQ oral history, King got the lyric wrong in his book, writing “Come on, Mary” instead of the song’s actual line: “Come on, baby.”

Then there were the more disturbing appropriations of “Reaper.” Blue Öyster Cult found themselves tarred with the same brush as other hard rock acts of their era, with uptight cultural watchdogs accusing these artists of promoting suicide among their young, impressionable fan base. In 1985, Susan Baker, one of the founders of the Parents Music Resource Center, spoke during a U.S. Senate hearing, putting bands like BÖC on blast. “Ozzy Osbourne sings ‘Suicide Solution,’” she said. “Blue Öyster Cult sings ‘(Don’t Fear) the Reaper,’ AC/DC sings ‘Shoot to Thrill.’ Just last week in Centerpoint, a small Texas town, a young man took his life while listening to the music of AC/DC. He was not the first.”

Roeser has spent much of his life since writing “Reaper” smacking down the theory that it’s about killing yourself. “It’s a love story that transcends the death of one of the partners and then they get back together again in another plane,” he has said. “It’s not about suicide, although I can see how people can think that, but that’s not where it’s at. It just imagines that there is an afterlife and that lovers will be reunited.” That “Reaper” evokes perhaps the most tragic fictional lovers of all time — “Romeo and Juliet / Are together in eternity” — only served to complicate the song’s meaning. Roeser intended the track to be romantic, but perhaps not in the ways critics believed it was — still, he certainly wasn’t romanticizing suicide.

By the time “(Don’t Fear) the Reaper” became the idea for an SNL sketch, the song’s supposedly-scary implications had long since evaporated. By the late 1990s, “Reaper” was a time-capsule piece, a dated stadium-rock relic. (Tellingly, the hit 1996 horror film Scream, which was largely a critique of the moribund slasher genre once popularized by Halloween, used a slowed-down, acoustic cover of “Reaper” as an ironic way to juxtapose the late-1970s with the then-contemporary late-1990s.) It was Will Ferrell who first started thinking about the possibility of a sketch in the fall of 1999.

“Every time I heard ‘(Don’t Fear) The Reaper,’ by Blue Öyster Cult, I would hear the faint cowbell in the background and wonder, ‘What is that guy’s life like?’” he later told Rolling Stone. But when Ferrell tried to pitch the concept at SNL, it was met with confusion. “Lorne (Michaels) was asking questions like, ‘Oh, is that a famous part of that song? The cowbell?’ We were all saying, ‘No — that’s why it’s funny.’ It kinda died in committee. In Lorne’s defense, I don’t know if it was its best version then.”

But Ferrell brought the idea back up when Christopher Walken hosted the April 8th, 2000 episode. It was Walken’s fourth hosting stint, and Ferrell felt like he would be right to play Bruce Dickinson, a cocky, all-star rock producer who brings “Reaper” alive in the studio. Even so, there still wasn’t a lot of enthusiasm for what Ferrell had come up with. “The sketch was kind of put at the back of the show,” Ferrell recalled. “I thought it probably wouldn’t make it.” In fact, “More Cowbell” was the last sketch of the night — SNL’s designated “This is so weird, and no one’s going to get it anyway, but let’s give it a try” sketch that airs in the wee early hours on Sunday morning when most people (before YouTube) had stopped watching and gone to bed.

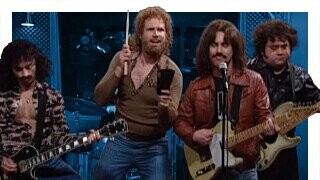

You probably don’t need a plot synopsis of “More Cowbell.” But briefly: The sketch is an imaginary Behind the Music segment in which BÖC are in the studio working on “Reaper.” Chris Kattan plays Roeser, Chris Parnell plays Bloom and Ferrell plays a guy named Gene Frenkle, who really gets into banging on his instrument, a cowbell. The rest of the group objects to how intrusive he’s being, but Dickinson insists that the cowbell is the key to the whole track. Frenkle and Dickinson were not actually part of the song’s making — Frenkle was a made-up character, and Dickinson was just somebody who worked for the band’s label. (“They looked at a greatest hits compilation,” Roeser said in the GQ oral history, “which is where they got the name Bruce Dickinson.”) But those two men became the stars of “More Cowbell,” the entire sketch built around Frenkle’s feverish determination to give “Reaper” more cowbell, thereby making the song a classic.

Ever since its 2000 debut, “More Cowbell” has deservedly become an all-time SNL sketch, even if it’s hard to watch for people like me who have an allergy to Jimmy Fallon and Horatio Sanz, who play the Bouchard brothers. (By the way, for some reason Fallon’s Albert is called Bobby.) Fallon and Sanz’s inability to keep from breaking was notorious on the show, and it’s especially annoying here — although, to be fair, they’re not the only ones having trouble keeping it together. (“Walken never broke,” Kattan told GQ. “He’s visiting from another planet, so he doesn’t understand.”)

Nonetheless, the skit worked precisely for the reason Ferrell explained to Michaels: We’d all subliminally heard the cowbell in “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper,” but we hadn’t picked up on it. “More Cowbell” made it the most prominent, hilarious part of such a seemingly somber song. You couldn’t unhear it afterward — and every time you heard it, you laughed. Here was this wicked guitar riff, flaunting its darkness and majesty, and then right after came this meager donk donk donk, an unintentional comedic counterpoint undercutting all that swaggering gloom.

The members of Blue Öyster Cult swear they got a kick out of the sketch. “I thought it was hilarious,” Roeser said in 2017. “I really thought it was funny, and I was grateful Will Ferrell didn’t savage the band. They did a sketch on Neil Diamond and really let him have it. I was glad it was funny and thought Christopher Walken was just brilliant.”

Nonetheless it was inevitable that, for the rest of their days, BÖC — the lineup has changed over the years, with only Roeser and Bloom remaining from the original quintet — would hear shouts of “More cowbell!” But they weren’t alone. In the GQ oral history, Parnell and Kattan admit they get it a bunch, too. And so does Walken.

“People … I don’t know … I hear about it everywhere I go,” the Oscar-winner said in October 2004. “It’s been years (since the sketch aired), and all anybody brings up is ‘cowbell.’ … You never know what’s gonna click.” When Ferrell was on The Tonight Show in 2019, he recounted going to a play that Walken was in: Afterwards, he went backstage to say hello, and Walken greeted him by saying (perhaps jokingly), “You’ve ruined my life” because of the sketch. (“People during the curtain call bring cowbells and ring them,” Walken told him.)

The sketch’s impact could also be surreal: Roeser occasionally would receive condolences from fans, believing that the fictional Frenkle had died. (At the end of “More Cowbell,” there’s an onscreen graphic that reads, “In Memoriam: Gene Frenkle: 1950-2000.”)

Still, at a time when poptimism was about to take hold, arguing against the long-held critical notion that rock music was clearly superior to pop music, “More Cowbell” seemed to signal a cultural shift in how the world looked at a BÖC. The long-haired, self-serious guys in the sketch weren’t just trying to craft a hit — they were trying to make something significant. Likewise, Dickinson’s imploring of Frenkle to “really explore the studio space” felt like the sort of pretentious nonsense that rock bands were increasingly engaging in during the 1970s. The bit’s underlying joke was that, for all BÖC’s furrowed-brow dedication to cracking “Reaper” in the studio, it was just a dopey song with a lot of cowbell. An invitation for young people to kill themselves? What a bunch of garbage: Didn’t everybody know “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” was just silly?

Blue Öyster Cult had one more Top 40 hit — 1981’s “Burnin' for You,” which felt similar to the catchy, anonymous arena rock of peers like Loverboy and Foreigner — but they soon started to flounder, losing band members and failing to maintain their commercial momentum. And, for a while, it seemed like they weren’t going to make any more records, releasing 2001’s Curse of the Hidden Mirror before finally returning to the studio in 2020 for The Symbol Remains.

“We had to overcome a fair bit of inertia to bring the project to fruition,” Roeser admitted, “but once the cobwebs had gone we became really excited about what we were doing. To a degree we had been happy to rest on our laurels and play our catalog on stage for quite a few years. It had become apparent that with our last two albums that we weren’t selling a lot of records any more, but that didn’t bother us because we were doing very well as a live act. One thing that did change was that we’d had a really good lineup for a number of years, and we knew it was time to make one final record. This may be our last record or it may not, time will tell.”

If you go to BÖC’s website, the band acknowledges their biggest hit’s permanent association with that SNL skit — slightly. In a 2020 news item promoting The Symbol Returns, it’s mentioned that former drummer Albert Bouchard came back to the fold to perform on the track “That Was Me,” noting that he “returns to add percussion (cowbell, of course).” Meanwhile, the sketch inspired listeners to keep an ear out for cowbell in other old rock songs — and prompted current groups to lean into the humor of including cowbell in their songs. When Queens of the Stone Age appeared on SNL in 2005 during an episode in which Ferrell hosted, the band played their killer track “Little Sister,” with the apparently resurrected-from-the-dead Gene Frenkle banging away on the cowbell — even though the percussive instrument in the song is actually a jam-block.

“Reaper” remains a juggernaut: In the GQ piece, Tannenbaum writes, “An industry source estimates that (the song) generated more than $637,000 in revenue in 2020, not including from album sales.” When you type “More Cowbell” into Spotify’s search engine, “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” is the first result that comes back. Maybe in some ways it’s now a punchline, but “Reaper” is nonetheless the song that defines BÖC, and also perhaps its era. It sounds like they’ve made peace with that.

“People ask me if there’s a song that you ever get sick of playing, and I would have to say whatever song it is, it’s not ‘The Reaper,’” Albert Bouchard said in 2021. “I love playing that song every time I played it. I’ve never not loved playing it.”

And maybe that’s another reason “More Cowbell” has resonated for so long. Sure, Ferrell is making fun of BÖC, but he’s also tapping into a truism. Rock ‘n’ roll may not be as fashionable as it was back in the day, but there’s still something glorious about the idea of you and your buddies getting together to make one big, awesome rock song. “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” is kinda silly. But it’s also kinda great. And maybe part of the reason why it’s so great is that it’s also kinda silly. That cowbell was always there. We just didn’t know to listen for it.