5 Movie Studio Scandals That Everyone Tried to Cover Up

Hollywood loves stories about Hollywood. They love stories that portray movies as a transcendental artform — if they had their way, every single picture would have a scene of a character staring at a movie screen, transfixed. There are some stories about the movie business, however, that Hollywood doesn’t enjoy telling. We mean the dirty ones, the true ones, the ones they cover up. Like the stories of how...

The Studios and American Humane Joined Forces to Cover Up Animal Deaths

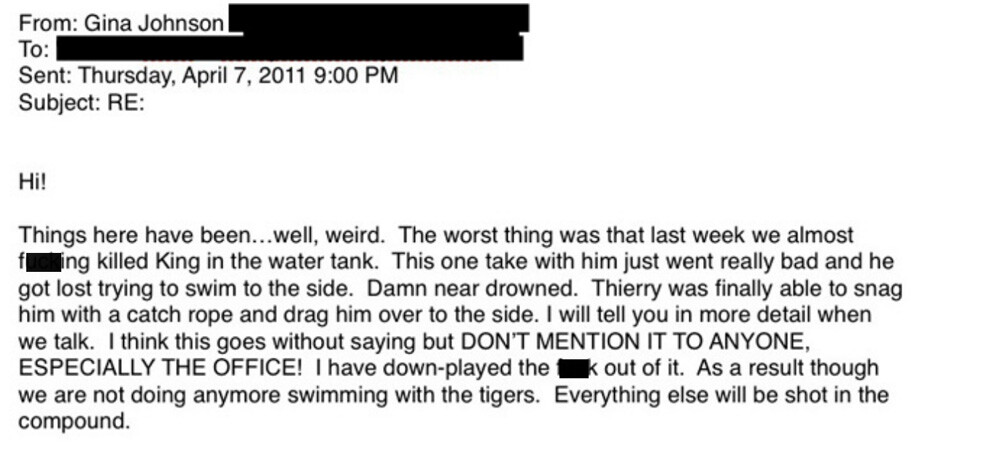

We don’t know how much you personally care about animal welfare. Still, none of us like to be misled, and when we hear that the American Humane Association (AHA) monitors productions, we think that means no animals are harmed, just like the organization’s seal of approval says. But that’s not always the case: Hollywood has had a long up-and-down history when it came to how it treated animals on set. About a decade ago, we got a fresh flood of reveals, in the wake of one HBO show killing a bunch of horses. For instance, the Hollywood Reporter obtained the following American Humane email about the tiger in The Life of Pi:

Which prompted some in the audience to ask, “Wait, weren’t the animals in Life of Pi CGI?” The answer: Many were, but no, they did use a real tiger. People also asked, “But didn’t this film say ‘No animals were harmed’ in the credits?” The answer: It did, but the AHA monitor on the scene was sleeping with a studio exec and was going to approve the film no matter what.

Still, it’s unfair to say the AHA offers certification in exchange for sexual favors. It looks more like they offer certification regardless. Consider the Hobbit films, which got a suspiciously specific certification saying, “American Humane monitored all of the significant animal action. No animals were harmed during such action.” Besides killing some horses, the production killed goats and sheep by dehydrating and drowning them. If you have zero memory of goats or sheep in those movies, don’t feel bad; they were pretty forgettable.

Or you have this bit of slapstick absurdity upon a chipmunk in the movie Failure to Launch:

Meanwhile, here’s the AHA internally noting Disney punching a dog on the set of Paul Walker’s Eight Below:

The AHA claims that 99.98 percent of animals it monitors go unharmed, but that stat takes into account math like “this movie used 50,000 ants and wasn’t cruel to any of them, so it’s cool if they set 100 gorillas on fire.” It seems the AHA issues their approval regardless because they’re really chummy with studios. The organization loves animals, but they also really like being invited to movie sets. And why not? Movie sets are magical places.

The Studio Head Who Embezzled, Took Over Another Studio and Blacklisted the Whistleblower

David Begelman was president of Columbia Pictures, where he embezzled over $60,000. Cliff Robertson, who played Uncle Ben in the Tobey Maguire Spider-Man movies, discovered part of this embezzlement when he spotted a fraudulent check with his (Robertson’s) forged signature. Columbia Pictures investigated and discovered the rest, but they stayed mum about what they found. They said Begelman was parting ways with the studio over emotional problems.

If Columbia merely chose mercy, that would be one thing. However, Columbia also reacted with fury and vengeance — against the people who called Begelman out. When Columbia wanted to reinstate Begelman in the middle of the investigation, and another exec Alan Hirschfield said to reject the guy who’d robbed them, they went through with bringing Begelman back and ousted Hirschfield. As for Robertson himself, he was blacklisted for years from getting any real acting jobs anywhere.

Columbia Pictures

We won’t detail all the other, unproven accusations against Begelman, but if you’re interested in what’s alleged to have gone on between him and his client Judy Garland, there’s a whole book you can read on the subject. Post-Columbia, though, Begelman seemed to land on his feet for a while. He became president of MGM, then CEO of United Artists, then ran another production company. He allegedly committed even more fraud, and he not-allegedly turned out to be a pretty unsuccessful producer.

Begelman’s career ended with him suddenly killing himself after his latest production company went bust. Hold on, does this story end unhappily for everyone? That’s the opposite of a Hollywood ending.

The Assault of Patricia Douglas

The #MeToo movement began as a reckoning against sexual misconduct of all kinds, but in the news, it quickly settled as an examination of one or two specific industries. The entertainment industry was the most prominent one, which is weird, because this is the field where everyone already knew sexual malfeasance controlled everything. The history of Hollywood is one long list of sexual revelations that everyone immediately pretends to forget about.

Here’s one that’s somewhat forgotten now but was a huge deal at the time: In 1937, MGM threw a big party for salesmen and trucked in a bunch of dancers dressed as cowgirls (telling the dancers it was a shoot, not a party). One dancer, Patricia Douglas, was raped in a car in the parking lot. An attendant saw her and sent her in a studio car to a studio-friendly hospital. No need to get the police involved, figured MGM. Douglas then broke from the norm by going public with what happened. The press covered the story, publishing her picture and home address — but declining to name the studio.

Daily Times

MGM worked to discredit her. They hired Pinkertons to delve into her romantic history, which could usually be relied upon for misleading arguments, but the detectives found nothing. They reached out to her doctor (unsuccessfully) for him to testify that he’d treated her for gonorrhea. They got to the parking attendant — he testified that the man he saw with Douglas was not MGM salesman David Ross, as she claimed, but some guy who wasn’t anywhere near as overweight. The attendant’s family later said he said this in exchange for an MGM job.

After the initial criminal trial didn’t pan out, Douglas tried suing, repeatedly. This too failed when, one day, the lawyers from both sides just didn’t show up. Some say that sounds like collusion, and some also said that the original DA (who’d previously been indicted for perjury during a rape trial) was on MGM’s payroll, but no one could prove anything. Douglas herself totally vanished for public view, with all chance of a career in Hollywood now gone. Rumors even said that MGM had had her killed, till a Vanity Fair writer tracked her down in 2003 at age 84 and got her story told — a few months before her death.

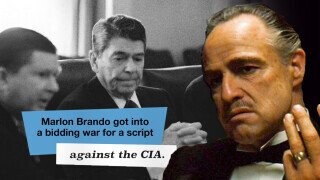

The Bidding War Between Marlon Brando and the CIA

The source for this next story is Frank Snepp, a former CIA analyst. Snepp was the CIA’s big Vietnam guy, and he wrote a memoir about the disastrous evacuation. The CIA sued him for this, claiming that though it apparently did not reveal any useful information, his revelations hurt agency discipline. Their argument worked, and the CIA won the rights to all his book royalties.

Snepp became a journalist for ABC, where he interviewed Eugene Hasenfus, the marine who got shot down while delivering weapons to Nicaragua, leading to everyone knowing about the Iran-Contra affair. Later, Snepp wanted to make a film about the scandal, using Hasenfus’ story. Marlon Brando was on board for the project, said Snepp, and so they set up a meeting at Brando’s mansion — Snepp, Hasenfus and a kimono-clad Brando.

Hasenfus wasn’t nearly as open to a deal as he’d first seemed. At the meeting, said Snepp, he revealed that Brando’s offer was being trumped by far by another offer, from a group headed by another intelligence guy. This guy, Larry Spivey, was supposedly a freelance movie producer, but when the New York Times poked into him, they found he worked out of a dummy office.

Pretty strange that this guy could outbid Brando (this was 1987, before Brando’s money problems). Snepp checked in with some of his contacts and discovered that Spivey bid for the film rights on behalf of the CIA, as part of a group controlled by Oliver North himself. Given that the Hasenfus movie never came out, we have to conclude that this was the CIA’s plot to bury the story, rather than (as we fully first hoped) their attempt at funding the project so it gained the widest possible audience.

The Adaptation So Bad, It Killed the Writer

In 1946, a Frenchman named Boris Vian said he’d discovered a promising young Black American author. This author, Vernon Sullivan, wrote a novel about a lynching victim’s brother who passes as white in the Southern United States. This guy concocts a revenge plot by sleeping with a plantation owner’s two daughters. The book was called I Spit On Your Graves (no relation to the similarly named revenge film I Spit On Your Grave).

via Wiki Commons

Sullivan couldn’t publish in America, said Vian, as they’d banned his books there. This claim should have raised some eyebrows. Anyway, when the book was released in France, it did indeed cause lots of controversy. Not because of all the detailed descriptions of sex with teenagers but because in 1947, the book was found at the site of a murder-suicide. Edmond Rougé, a salesman (we apologize to all salesmen reading this for once more characterizing your profession as sexually violent), was having an affair, then his mistress broke it off. He strangled her. The protagonist of I Spit on Your Grave strangled one of his conquests in the same manner. Rougé killed himself, leaving the book open at that very passage, reported newspapers (it is unclear if he really did).

Perhaps we need to hold Sullivan accountable for his writings, said moral guardians. France, despite imagining itself to be more open-minded than puritanical America, fined Vian for his part in translating this dangerous work. Then when on trial and under oath, Vian was forced to reveal the truth. There was no Vernon Sullivan. Vian had written the book himself.

Studio Harcourt

The scandal did not hurt book sales. Quite the opposite. And a decade later, the book got turned into a film. Like many protective authors, Vian disavowed this adaptation of his work, formally asking that his name be left off the credits. Nevertheless, he attended the premiere and viewed this unfaithful translation. His last words are said to have come 10 minutes into the film. “These guys are supposed to be American?” he said. “My ass!” Then he had a heart attack and died in his seat.

Damn, Vian. Even Alan Moore didn’t die when he heard about V for Vendetta (which, by the way, would have been an excellent alternate title for I Spit On Your Graves).

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.