5 Dumb Reasons Competitors Got Disqualified

In 1988 (so the story goes), a Swedish magician named Lennart Green performed a card trick at a competition. It was so impressive, the judges concluded that the random audience members who’d shuffled the deck must have secretly been in league with Green, and they disqualified Green from the event. Three years later, Green came back, this time letting the judges shuffle the deck themselves, proving they’d been wrong to kick him out before.

We say “so the story goes” because we had some trouble verifying this tale, as the sources are all magicians. But if you found it interesting, strap yourself in, because we’ve got more questionable disqualifications for you below.

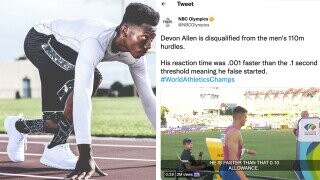

Multiple Runners Got Disqualified for Too-Fast Reflexes

Don't Miss

Devon Allen is on the Philadelphia Eagles’ practice squad, and he used to play football for the University of Oregon. In the six years between college and today, he focused on track and field, representing the U.S. at two different Olympics (2016 and 2021). He also competed in three different World Athletics Championships, which is on par with the Olympics when it comes to running. The 2022 championships were in Eugene, Oregon. That makes it sound more like a county fair than something major and global, but it’s usually held somewhere bigger and is a huge deal, we promise.

In last year’s championships, Allen ran the 110-meter hurdles event. He’s held the national title in that event three times. He’s finished it in 12.84 seconds, which is among the fastest finishes ever and faster than anyone clocked at the 2022 championships. But unfortunately, he got disqualified for a false start. A false start normally means the athlete started running before the starting pistol fired, and Allen started after it fired, but not long enough after. Sensors said he took off 99 milliseconds after it fired, and the rules say athletes must start 100 milliseconds after, or later.

Human reflexes don’t work instantly. A runner who starts immediately upon hearing the signal will take at least 0.1 seconds to get moving, say the rules. That means if a runner moves any sooner, the signal must not have yet fired when they tried to start, even if did fire by the time they actually started.

Judges have disqualified other people for the same reason in the past. In 1996, for example, British sprinter Linford Christie ran a false start for setting off 0.086 seconds after the signal. Today, however, we have data that proves this rule is dumb. A dozen years ago, the organization behind the World Athletics Championships commissioned a study, and it determined that, yes, humans totally can have reaction times shorter than 0.1 seconds, so a threshold of 0.1 seconds makes no sense. The study recommended switching to 0.08 or 0.085.

Or how about this instead? We already measure runners’ exact start times and finish times in milliseconds. So why don’t we just give the medal to whoever finishes the race quickest, no matter who finishes first? If you start 100 milliseconds before your competitor and finish 20 milliseconds before them, we don’t need to disqualify you. We just place you after them because you took 80 milliseconds longer. If you start 100 milliseconds before your competitor and finish 120 milliseconds before them? You win.

The Oscars are a giant pile of wormy bullshit. Complaining may be missing the point. It’s a group of insiders giving awards to themselves — if we care about who really deserves praise, we should listen to critics’ choices, not awards (or we should listen to the Critics’ Choice Awards). Heck, the only reason the Academy Awards exist is because Louis B. Mayer thought awards were a great way of keeping people in movie business from unionizing. That sounds like a nonsensical conspiracy theory, but it’s true.

Who makes Steve Guttenberg a star?

We do... We do...

Still, we feel bitter when the Oscars get it especially wrong. Like in 1983, when Disney submitted the previous year’s Tron for Academy consideration. The Academy said it was ineligible for the Best Visual Effects award because its use of computers constituted cheating.

This was a ludicrous decision, on several levels. First, we all know in hindsight that computer effects are indeed visual effects. Though practical effects often look better than computer effects, we also have computers to thank for some of the best special effects ever, and Tron’s were groundbreaking. But it was also an absurd decision because most of Tron’s effects didn’t even use computers. The production made hundreds of matte paintings. They inked tens of thousands of frames by hand to achieve that distinctive glow. Then when it came to CGI, the movie arguably contained no computer animation because they could only use computers to create individual still images, and the filmmakers had to use traditional methods to string those stills together.

Walt Disney Pictures

In time, the Academy would wise up. Just a few years later, they’d give the Best Visual Effects award to the Harry Potter-esque Young Sherlock Holmes, the movie that premiered the first-ever CGI character. But in 1983, they reserved their accolades for such forgettable, unworthy recipients as *checks the nominations that year* E.T., Blade Runner and Poltergeist.

Huh. Okay, they didn’t make bad picks instead of Tron. 1982 was just a hell of a year for movies.

Men Were Banned from a Gay Softball Group for Being Insufficiently Gay

Every year since 1977, the North American Gay Amateur Athletic Alliance has organized a national Gay Softball World Series. Dozens of local gay leagues send teams to compete, and there’s long been a fear about players’ legitimacy. Specifically, people have feared that some teams recruit secretly straight players to gain an edge. So the Alliance passed a rule that each team can have no more than two heterosexual players. In 2008, they disqualified a San Francisco team for breaking this rule, and three of the affected men sued.

“That proves nothing! By that logic, everyone would be eligible!”

This sounds totally like a 2008 sitcom plot. Didn’t South Park air like three episodes in a row when the premise was “what happens when the discriminated group starts discriminating?” If nothing else, South Park would have had some fun with the Alliance’s acronym. But this story did not end with a lesson about how, yes, discrimination is always wrong, as we’ve learned through this funny reversal. This disqualification was wrong, but there was more to the story than that.

First, a judge ruled that the Alliance can legally keep straight men from playing. That part’s not wrong. Freedom of association includes the right for private organizations to discriminate. When individual organizations discriminate against a certain group or a certain point-of-view, that doesn’t necessarily hurt groups or views. In fact, it can accomplish the opposite. If every organization had to admit everyone, no organization would end up with any identity other than the majority one.

High Times

“Whoa whoa whoa,” you’re probably thinking. “So what you’re saying is it’s legal for some club to ban (insert marginalized group here)”? It may not be, but that’s because a law singled out that group or type of group, saying that without some specific legal protection, they’d face discrimination from just about everywhere. If a group wouldn’t face that, but one random organization does ban them, that’s not really a problem.

Which prompts a question: Why did these straight men want to play gay softball anyway? Was it just a matter of principle? Here’s the other twist: The men were never straight. The rules restricted straight players, but the men were bi. One had a wife, but still, he was bi, and the guys wanted to be part of an LGBTQ+ organization for the same reason everyone else there did. And so, though they won the lawsuit, the Alliance settled with the men, added official language to the rules saying they’re cool with bi and trans people too, and they gave the San Francisco team the second place title they’d earlier stripped from them.

A Boxer Failed His Weigh-In — For Eating After a Bad Call

Boxing is one of the oldest sports, being part of the Olympics all the way back in 686 B.C. In Olympic boxing, we don’t just hand a medal to whoever’s still standing in the end. A knockout ends the match, sure, but with or without that, a team of judges assign each boxer a score. The way it works today, the entrant who boxed better gets a 10, while the other usually gets a 9 but may get as low as a 6 depending on how much the winner dominated them. In previous years, judges had to assign scores by counting individual punches.

In 1936, Thomas Hamilton-Brown from South Africa boxed in the Olympics, competing as a lightweight. He went up against Carlos Lillo from Chile, and neither knocked the other out, so the match came down to the score. The judges scored Lillo higher, leaving Hamilton-Brown the loser.

Hamilton-Brown spent the next few days probably sulking and definitely eating. He went on a big binge (lightweight boxers commonly restrict their diets severely before bouts to ensure they don’t exceed their weight class). Then he learned that the judges made a calculation error. It had been a split decision, and when they tallied the points correctly, Hamilton-Brown had won after all. Victory!

That meant he’d graduated to the next round. Which meant another weigh-in. But thanks to his binge, Hamilton-Brown was no longer a lightweight. And so, he got disqualified after all, and Lillo proceeded into the next round.

Doesn’t seem fair, right? When people box, we don’t really care how much they weigh. They aren’t sumo wrestling. We just use weight classes as a rough shorthand for strength classes, and Hamilton-Brown was no stronger than during the last weigh in — he couldn’t have gained five pounds of muscle since the last one. This probably wasn’t the worst injustice going on in Berlin in 1936, but still.

A Race-Car Driver Was Also Called Back After a Bad Disqualification. Chaos Ensued

Auto racing is a sport of both skill and science. The drivers need to be able to operate the car well, of course, but the car must also be a technological marvel. At Le Mans in 1953 — an endurance race in which cars speed along a track for 24 hours — the Jaguar team was showing off a fancy bit of new technology: disc brakes.

Okay, disc brakes might sound like a very basic piece of the car to you, but it was revolutionary to racing. Most cars used drum brakes, in which objects called shoes push out against the rotating wheel to stop it moving. Shoes wear down. Disc brakes clamp on the wheel and don’t wear down as fast. So, though the Jaguar’s competitor, a Ferrari, offered more power overall, the Ferrari drivers had to be little careful with the brakes, while the Jaguar could just go nuts, leaving deceleration till as late as possible.

via Wiki Commons

Driving number 18 in the race for the Jaguar team were Duncan Hamilton and Tony Rolt. One problem, though: During the practice round, some teammates went on the track in a different car that was also labeled number 18. This meant Hamilton and Rolt’s car was just a practice car and should not be allowed to drive, argued the Ferrari team. We are not entirely sure they were arguing in good faith, but that’s how Hamilton and Rolt got disqualified.

When Thomas Hamilton-Brown got disqualified from his boxing match, he binged on food. When Brits in France get disqualified from theirs, they tend to binge on something else. We should mention that Rolt would go on to deny that he and Hamilton were found severely hungover the next morning, when they learned that their appeal had gone through and they were allowed to race again. He also denied that, as Hamilton claimed and press reported, they then drank some brandy to steady their twitching arms.

But there’s no denying that they ended up tearing through the race with a broken windshield, and as they raced at 130 miles per hour, Hamilton’s face slammed into a bird, shattering his nose. They broke the race’s speed record and came in first place. Brakes, breaks, brandy and birds. These are the secrets to driving — according to BBBB, the less reputable cousin of AAA.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.