Examining the Accuracy of 5 Historical Figures in Monty Python

Monty Python were a group of educators, devoted to teaching British children about history. You might have heard they were a comedy troupe, but this is just a common misconception, stemming from how their lessons would sometimes get very silly.

Just how accurate were their portrayals of men from history? Sometimes, the real-life figures were crazily different from what you saw. Other times, they were surprisingly similar, and this was actually even crazier.

Karl Marx, The London Rascal

Don't Miss

The Python sketch “Communist Quiz” features four notorious communists: Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, Ché Guevara and Mao Zedong. A game-show host asks them questions, chiefly about British soccer teams, and the men fare poorly. Marx (Terry Jones) is the star of the show, as he gets his own special one-on-one lightning round, but though he requests the specially tailored topic of “workers’ control of factories,” the host returns to soccer questions, spelling Marx’s doom.

The crew all dress up as the men they’re playing. Ché Guevara has a cigar and hat. Mao has... well, you can look at Terry Gilliam in the video to see how they made him look like Mao. Marx sports his famous beard. But did you know Marx ditched his facial hair in the last years of his life? Immediately after getting one famous photo taken, he cut off his hair and beard, and no one knows this because no photo of him after this survives.

The big joke of the sketch is that these four figures would be inappropriate guests for a British quiz show. Before the questions start, we think this is some kind of political panel discussion. When the questions do start, of course these guys wouldn’t know British sports minutiae. But don’t be so sure about that last part. Sure, Marx wouldn’t know who won the 1949 FA Cup Final, since he died 60 years before that, but he did know a thing or two about British hobbies. He lived in London for the last three decades of his life.

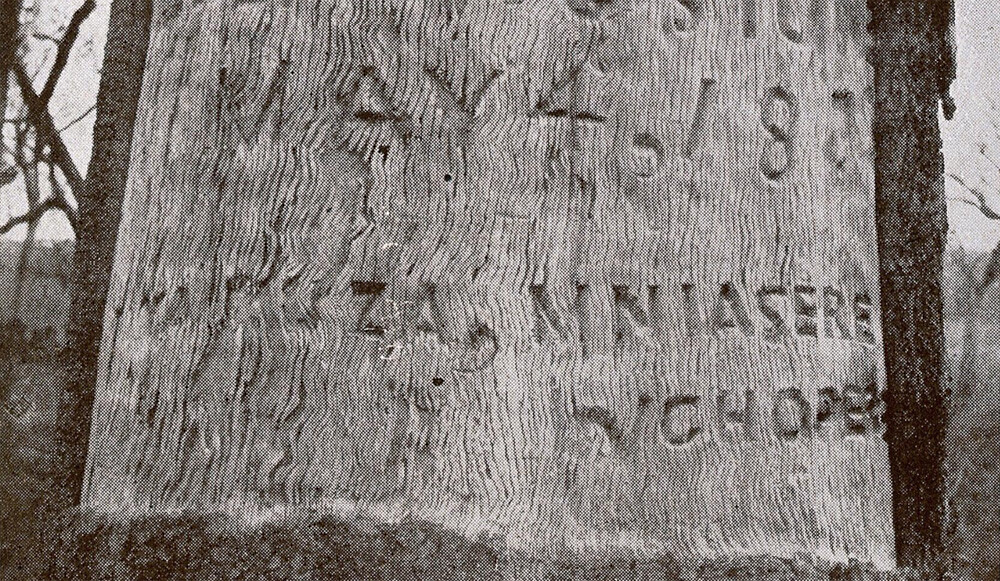

He also knew a thing or two about lad culture, based on the recollections of Wilhelm Liebknecht, a German socialist in London. When another friend of theirs came to town one day for a pub crawl (“making a beer trip”), the gang decided to drink at each of the 18 pubs on Tottenham Court Road. They sang with some strangers they stumbled on, and they exchanged blows with others. Then, thoroughly drunk, they wandered the streets and came upon a pile of paving stones.

“In memory of mad student’s pranks,” they picked up the stones and threw them at streetlights, smashing four or five of them. Policemen heard the smashing and showed up, then the three guys ran off, with the officers chasing them. Marx ran surprisingly fast, they took a few strategic turns and the drunk communists ended up behind the bobbies.

We don’t know if “Yakety Sax” spontaneously played during all this. But we do know the only reason Monty Python didn’t make this into a sketch is that it had already happened for real.

Michelangelo and the ‘Creative’ Last Supper

Sorry, that last sentence makes no sense. Sometimes, Monty Python did sketches from things that totally did happen for real.

In their “Last Supper” sketch, we see the Pope confronting Michelangelo about his attempt at painting this most holy meal. The unseen painting contains 28 people in it besides Jesus, plus a kangaroo and a cabaret. The artist considers changing it to conform to the Pope’s demands for accuracy, then he figures he can just dodge all complaints by changing the name, saying it depicts some meal other than the Last Supper.

That exact thing happened. Not to Michelangelo, but Monty Python only went with Mike for the sketch because he’s a famous artist other than Leonardo, who did the Last Supper we all know. In real life, it happened to Paolo Veronese, a Venetian painter who was 36 when Michelangelo died. In 1573, Paolo painted the Last Supper. He took such liberties with his depiction that he faced heavy criticism, and in the end, he renamed the painting, to The Feast in the House of Levi, after a totally different New Testament story. For this painting, we don’t need to just imagine the absurdity. Here it is:

The Feast in the House of Levi has even more people than Michelangelo’s 28. We don’t see a kangaroo (16th-century Europeans didn’t know about kangaroos), but we do see multiple dogs in there. You can also say there’s a cabaret, as we see musicians and even a dwarf jester with a parrot.

We don’t think you’re supposed to know about Veronese to appreciate the Monty Python sketch. In fact, knowing the real story makes the sketch sound nowhere near as creative and absurd. The real story was actually crazier than how the sketch portrayed it. Veronese didn’t merely face critiques from his patron. For this sacrilegious painting, he was put on trial before the Inquisition, and no one ever could have expected that.

The Dissection of Dr. Livingstone

In the troupe’s film The Meaning of Life, we get a scene in Natal, in what’s now South Africa, during the First Zulu War. A soldier was bitten terribly during the night — not by mosquitos, as we first think, but by a displaced tiger.

He is diagnosed by one Dr. Livingstone. You might presume this is Dr. David Livingstone, what with this being 19th-century Africa. Wikis will assure you that you’re correct. And yet Livingstone died in 1873, and this scene takes place in 1879. We know this because they flash us with a card saying it’s 1879, something they don’t bother with for any other scene in the film. Livingstone’s presence isn’t enough of an anachronism to be a joke, just enough to be inaccurate. One might almost think these writers aren’t taking any of this very seriously.

Livingstone died in 1873, and he was laid to rest in Westminster Abbey nine months later. His body went on quite a journey during those nine months. First, he was totally in the hands of his two longtime attendants, Chuma and Susi. Chuma had been a slave before Livingstone’s expedition found and freed him, while Susi was from the Shupanga tribe. The duo spent two months taking Livingstone’s body a thousand miles to a town. Then a British explorer took custody of the body, took six months more to get it to its next checkpoint, then it landed on a ship bound for England.

Livingstone was buried in London, but his heart will always be in Africa. Literally. Because before they moved his body to town, Chuma and Susi cut out his heart and buried it.

We wonder what Livingstone would have thought about that. Hey, maybe you would be cool with the tribe you hung out with memorializing you in their own way, but Livingstone was a missionary, and his main purpose in Africa was to convert “heathens” to Christianity. He failed pretty hard at that, by the way. During all his years on the continent, he managed to convert just one person — a chief named Sechele. When Livingstone met him, Sechele ruled just half a tribe, having fled into the wilderness at 10 when his father the chief was murdered. Sechele was now on a quest to kill his uncle. We are not making this up, even though this true story sounds remarkably similar to Hamlet, and even more like Hamlet’s predecessor Amleth, and most of all like the Hamlet-inspired Lion King.

Livingstone converted Sechele and urged him to make peace with his uncle. Sechele agreed and gave his uncle a gift: some packaged gunpowder he could use. The pair then realized they weren’t in a tragedy but a comedy. The uncle, suspicious of the gift, tried to burn it, and so, it exploded and killed him, making Sechele the undisputed chief after all.

When Livingstone left the village, he was convinced Sechele had lapsed as a Christian, having turned to adultery. But the chief went on to have a well-documented life that included returning to Christianity, growing his tribe a hundredfold and getting thousands of people to voluntarily become Christians, more than any foreign missionary in Africa ever managed.

Noël Coward, Spy

Also in The Meaning of Life, we get the following song, sung by someone who is not Noël Coward. The script specifically identifies him as “Not Noël Coward,” so he’s clearly not the famous playwright and singer.

“Isn't it awfully nice to have a penis,” sings Not Noël Coward. “Isn't it frightfully good to have a dong? It's swell to have a stiffy, it's divine to own a dick. From the tiniest little tadger, to the world's biggest prick.”

Did the real Coward like penises as much as the singer of the Penis Song? Of course he did — both his own penis and others’. People didn’t generally call themselves “openly gay” back in the 1930s, but Coward said his sexuality was no secret. “There are still a few old ladies in Worthing who don’t know,” he once joked.

He had other secrets, though. Like how, during World War II, he was a spy.

In 1942, he starred in a propaganda film called In Which We Serve, backed by the Ministry of Information (aka, the Ministry of Silly Wonks). The film was huge, possibly the biggest British film of the year, and it was also the film debut of Richard Attenborough. This wasn’t a secret: Everyone knew about In Which We Serve. They didn’t know, however, that the British Foreign Office also recruited Coward to travel the world as their secret agent to push prominent figures to support Britain.

He traveled to Russia, and in 1940, he went to the Unites States. His British fans thought he was fleeing his own country to avoid having to fight. He asked his handlers if he could drop the secrecy and make his status as a government agent public, but they refused. They believed he had to work undercover for his persuasion campaign to work.

The King wanted to knight him for his service, but Winston Churchill recommended against it, possibly finding Coward a bit too queer. Decades later, he got knighted after all. People assumed it was just for writing funny plays, but the Royal Family generally don’t hand out knighthoods just for comedy. Sure, Michael Palin got one, but that was for his contributions to “travel and geography” — i.e., for hosting travel shows on TV.

And speaking of knights...

The Black Knight

Taking a look now at Monty Python and the Holy Grail, we have a whole lot of different figures whose historicity we can analyze. We could try to look into whether there was a real King Arthur, or examine what the Merovingians really were like. Instead, let’s talk about the Black Knight.

Yes, the knight who keeps trying to fight even as every one of his limbs get chopped off. That... can’t possibly be based on a someone real, can it?

It can. Monty Python took inspiration from Arrhichion, an ancient Greek athlete. Arrhichion took part in the Olympics of 572 B.C. and 568 B.C. His sport was pankration, a fighting event that combined wrestling and boxing. We think we are legally allowed to show you this sculpture of the event:

Arrhichion died during his final pankration match. He also won that match. Sounds impossible, but here’s how historians described the event: He and his opponent were locked in combat. The opponent got his hands around Arrhichion’s neck, a hold that’s barred in most modern competitions. Ultimately, Arrhichion suffocated and died. The opponent also dug his foot behind Arrhichion’s knee, and when Arrhichion squeezed him in this knee hold, it broke the opponent's toe or dislocated his ankle. Though Arrhichion died, it was the opponent who cried surrender, and so the dead man was declared the victor.

The story features no knight. But we’re imagining the opponent’s cry of pain, and we conclude that it did have someone who said, “Knee! Knee! Knee!”

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.