5 Wills of Millionaires That Wreaked Absolute Havoc

You know the correct way to handle your affairs when you die. You invite all your heirs to your mansion, leaving behind a will saying your fortune’s up for grabs. Whoever uncovers your murderer’s identity wins everything. In the end, perhaps your heirs never do learn the truth behind your demise, but they do learn something — about each other.

Unfortunately, not everyone takes this sensible route, leading to crazy situations like the following.

Secret Asian Children Successfully Claimed The DHL Founder’s Money

Don't Miss

The shipping company DHL was founded by three men, one whose name started with a D, one starting with an L, and the central guy, Larry “H” Hillblom. Hillblom died in 1995, in a most exciting prologue for the fight over his half-a-billion-dollar fortune. He was flying a World War II seaplane to an island in the Pacific, on a quest to explore a volcano. The two other men with him were the pilot and a major politician from the Northern Mariana Islands (the country where Hillblom claimed residency). The plane crashed, killing them all.

USGS

Hillblom grew up in California, and his will left all his money to UC San Francisco. He never married, and he had no children, as far as anyone knew. Then, after his death, eight different people popped up saying he had fathered children, he’d fathered children with them, and these children should inherit his estate. These maybe-baby-mamas were from the Philippines, Vietnam, and Palau. They claimed that Hillblom had visited those countries on “sex safaris,” impregnated a bunch of locals, then took off.

A sex safari sounds like an awesome way for a millionaire to spend his time. Then you think for a few seconds about why a millionaire should have to visit foreign brothels and bars to satisfy his sexual appetites. Hillblom liked sex with teens. Several of the people suing him were still teens when he died, with one 16-year-old, for example, alleging a sexual encounter from years before.

So this is a legal fight over hundreds of millions of dollars. On one side are a bunch of poor residents of distant Asian countries, some of whom are sex workers and some of whom are literal children suing on behalf on babies. On the other side’s the University of California, as well as Hillblom’s mother and brother. The plaintiffs have no way of proving paternity, as the man’s body is gone. Years later, a buried bag of his belongings with DNA traces will be found, suggesting someone deliberately tried to hide them, but as far as everyone knows now, Hillblom left behind no DNA samples.

You might guess how this ends, but you might be wrong. A court issued an order for DNA testing — not testing Larry himself, as he was unavailable, but testing the claimants for shared DNA. Tests proved these kids from different mothers and such different locations shared enough DNA to suggest a common father, lending sufficient credibility to their mothers’ claims.

Under Northern Mariana Island law, this entitled them to a share of the Hillblom estate. Not a nominal share, but $90 million each (which ended up still $50 million each even after taxes and stuff). The kids relocated to the U.S., both because they could afford to and for their own safety, as some of them had become among the richest people in their own countries and were now major targets.

Hillblom could have denied all of them money by a single line in his will disinheriting anyone he’d neglected to name, offspring or not. Such a “disinheritance clause” is actually standard in wills like his. Alternatively, he could dispute their claims by arriving in person, revealing he never died at all. We know we said he died in 1995, but that’s just because he was legally declared dead. After that plane crash? No one ever found his body, so he might be living in his volcano to this day.

One Guy’s Will Took 117 Years To Sort Out

We once told you about the bizarre case of a New Orleans businessman, whose estate took so long to figure out that by the time the court awarded his daughter $1 million, she was dead, because the case had lasted 78 years. That sounded crazy to us, but one earlier case from England has it beat.

William Jennens died in 1798 as Britain’s richest man, excluding royalty. He got his fortune the way all proper British people do, by inheriting it, then he grew it by lending to casinos and by spending hardly anything. He died without having signed a will. Supposedly, he’d meant to sign one, but he couldn’t find his glasses.

Relatives, distant relatives, and pretender relatives now all vied in court, claiming to be Jennens’ rightful heir. That case alone might have offered enough twists to stretch out for years or decades. But lawyers all over the world next reached out to anyone named Jennens (or Jennings), saying they too might have a shot at claiming the fortune. Whole clubs formed of these heirs, most commonly in the U.S. but also everywhere from Ireland to India to Australia.

This estate attracted more vultures than most for several reasons. First, of course, it was such a huge fortune and such a famous case. Second, England has special poorly understood rules that made it sound plausible that the bank should dispense funds to whoever claims them. Third, unlike most British people who died owning anything close to that much money, William the Miser had some gaps in his immediate genealogical record, leaving enough room for many people to claim shared blood. Plus, the name Jennens was common enough that people with that name spanned the globe, but it was just rare enough that such people felt it notable that they had the man’s name.

FX

“We live in the 1980s, and ‘Jennings’ is just our alias, and we are fictional, but maybe!”

In the 1850s, when the case had dragged out for over 50 years, Charles Dickens wrote Bleak House. It features an estate case likely based on Jennens. Dickens’ Jarndyce v Jarndyce ends when legal fees consume the entire fortune under dispute. This is supposed to be a ridiculous punchline to the plot, and it leaves the characters laughing.

That’s also how the real-life Jennens case ended up resolving. Another sixty years passed, all the money went to lawyers, and many claims still existed, but nothing remained for them to claim. Dickens was long dead by this time. So was every person who originally sued the estate when Jennens died. So was, in all likelihood, every single person on Earth who had been alive at the same time as the man.

A dead man’s money still being sorted out 117 years later — that’s a pretty big failure all around. However, you can also make that happen on purpose:

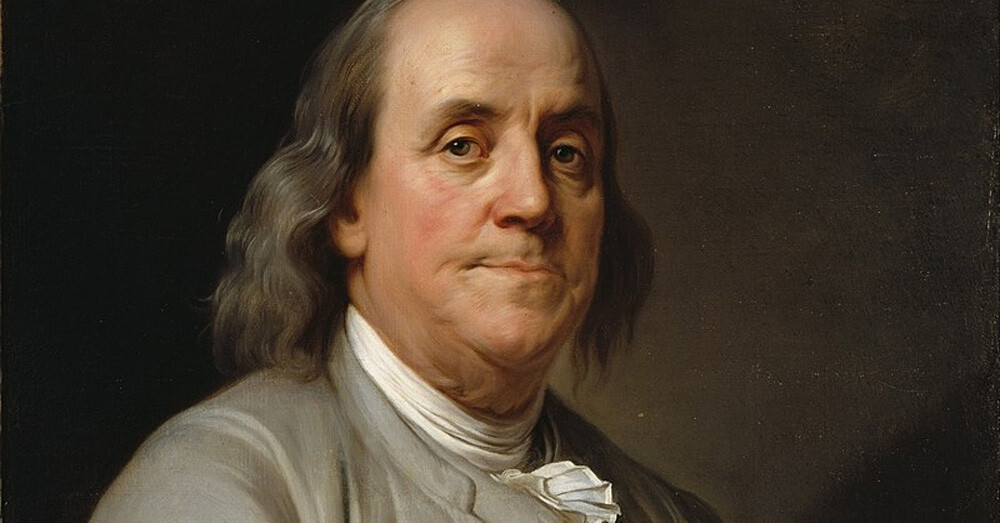

A Bitter Millionaire Left His Money To His Distant Descendants

When Ben Franklin died, he left behind the 1790 equivalent of $1 million in a trust, which could be doled out in parts or invested after 100 years and could only be cracked opened in full after 200 years. Once that much time passed, Boston and Philadelphia would split the money, plus interest. And so, in 1990, these cities found themselves with a $6.5 million gift from the long dead Ben Franklin.

Franklin’s gift showed his faith that the world, the young nation, these specific cities, and a functioning legal system would all continue for centuries after his death. It also showed off a general spirit of beneficence, as he wanted to help people but not specifically anyone he knew personally. Our next story is a twisted version of that.

Wellington Burt was an American lumber tycoon, and he died a rich man in 1919. In his will, he left his kids around $1,000 each annually, which was the same endowment he left each of four servants. This wasn’t like Bill Gates, who says he’s leaving each kid just a few million each so they can stand on their own — this was a deliberate attempt to spite his family, over some feud that’s now been lost to history.

via Wiki Commons

The bulk of his fortune, he put in a trust, to be distributed among his heirs after one specific condition came true: His last grandchild had to have been dead for 21 years.

Decades passed. His children died, grandchildren died, and even several great-grandchildren died without the trust paying out. Finally, in 2011, 92 years after Burt’s death, the stipulation kicked in. Twelve of his descendants split the sum, which now totaled $110 million.

If he loved his kids, like a normal person, Burt would have left the money to them, and if he loved his family but not his kids, his will could have named other relatives instead. If he loved the world in general, he could have left it all to charity. But we have to conclude Wellington Burt hated his family and hated everyone else as well. What he loved was his genes, and he wanted to shower his genes with riches a century in the future.

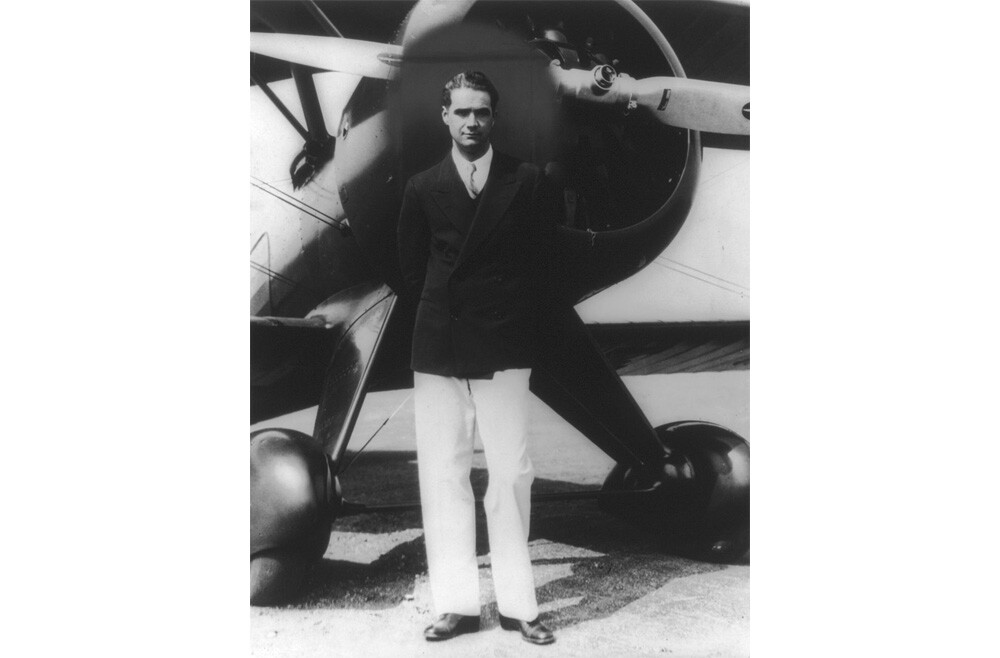

Howard Hughes’ “Mormon Will” Left His Money To Some Weirdo In The Desert

Howard Hughes died intestate in 1976. “Intestate” means “without leaving a will,” and we couldn’t end this article without using that fancy word at least once. Hughes’ $2.5 billion estate went to 22 different cousins, with the legal case deciding this lasting seven years. That’s quick compared to, say, William Jennens, but’s it’s still a fair bit of time, and if you track down every last piece of the Hughes estate, you’ll see that courts were still tying off loose ends in 2010, 34 years after Hughes died.

Miramax Films

We say Hughes died intestate because the courts declared this to be true. That ignores, however, one purported will of his that turned up at the headquarters of the Mormon church in Salt Lake City. The will appeared to be in Hughes’ handwriting and appeared to bear his signature. It divided his estate into 16 parts, with one going to the Mormon church.

Suspicious as that bequest was, that wasn’t even the weirdest part of the will. Hughes also apparently gave one-sixteenth of his money to some guy in Nevada named Melvin Dummar — though the will misspelled this name as “Melvin DuMar” and misspelled many other names too. Dummar was in fact the man who'd delivered the will to the Mormon headquarters, as he revealed after some prodding.

The way Dummar told it, he had met Howard Hughes just once. In December 1967, he spotted a man lying in the desert beside the Nevada highway. Almost perfectly reenacting the Good Samaritan story, Dummar helped this injured traveler, who asked for assistance getting to his hotel 150 miles away in Las Vegas. When they parted, the traveler revealed who he really was. The man’s name? Albert Einstein.

It was an outlandish tale, totally unbelievable. If true, it could well be one of the top 20 strangest things Howard Hughes ever did. A jury declared the Dummar will a forgery. Still, it had to be a pretty convincing forgery, right, to even reach that stage of investigation instead of everyone dismissing it out of hand? And authorities never charged Dummar with anything, even though if he really did forge that will, that was an attempted fraud worth over $150 million.

Thirty years later, a retired FBI investigator interviewed some of Hughes’ old employees, who now claimed that, yes, despite the staff’s old testimony, Dummar did rescue Hughes that day in 1967. The strangest part of Dummar’s story was true. Now, we don’t have enough information to declare whether Hughes’ “Mormon will” was genuine after all. But we’ll repeat what we said about the DHL guy’s case. If a court case pitted random gas station worker Dummar against a bunch of powerful heirs, we’d expect the court would end up siding against Dummar, even if his claim were valid.

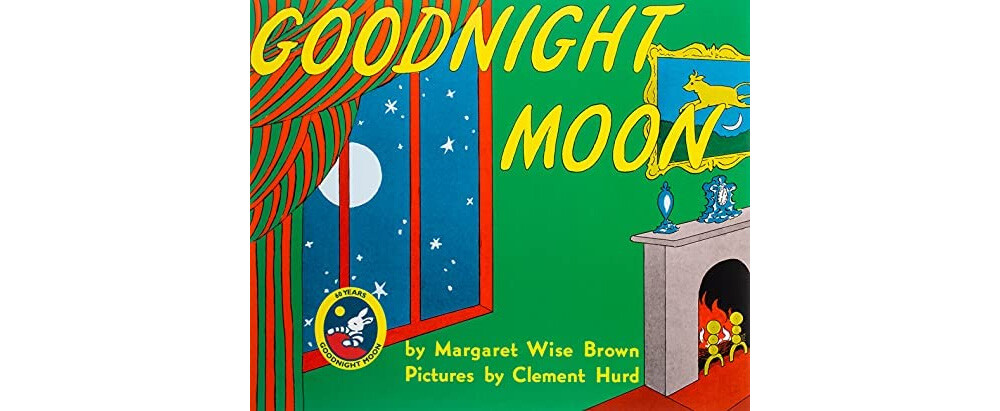

Goodnight Moon’s Royalties Sealed A Little Boy’s Doom

Margaret Wise Brown wrote over 100 children’s books, including the famous Goodnight Moon. If no one ever read the book to you as a kid (negligence that qualifies as abuse), you still surely know the text from various parodies. “Goodnight desk, goodnight mess, goodnight bribes from Bangladesh,” someone will randomly post following the retirement of, say, Biden.

HarperCollins

When she was 42, Brown was in France and underwent emergency surgery. Some sources say it was to remove her appendix; some say an ovarian cyst. The operation went fine. Then when a nurse asked her how she felt afterward (according to popular account, anyway), she said “Grand!” and did a high kick. This sent a blood clot, which had formed in her leg, up toward her brain, killing her.

Her will left the royalties from almost all her books to a nine-year-old boy, Albert Edward Clarke III. Albert would later claim she was secretly his mother, but no one believes this. He was just a neighbor, and Brown and his family were close. For a while, she’d had to pass through their building to get to her own house. She also might have written this will as a first draft or a joke. She hadn’t expected to die so young. “It occurs to me that it wouldn't be a bad idea to have a Will,” she wrote to her lawyer a few months before her untimely death, explaining the document, “so that the rapacious State of New York cannot take one-third of my horse brasses and Crispian.” Crispian was her pet dog.

Over the next 50 years or so, that inheritance paid Albert $5 million. That’s a nice bit of money to have waiting for you, especially in those days. You might say it meant he never had to work a day in his life. Indeed, he never did end up holding a steady job.

He dropped out of high school. He went on to be arrested dozens of times, for offenses ranging from trespassing to grand larceny to assault. One year when the trust paid him over $100,000 in today’s dollars, he lived in a van with some homeless woman he met on the street.

When his trustee died, he received a lump sum of saved money, and he got more reckless. He’d buy houses and then somehow end up selling them for half what he’d paid. He’d buy clothes but he never did laundry, he just threw each piece out when it got dirty or wrinkled. He became homeless multiple times. When the Wall Street Journal caught up with him in 2000, he’d received $341,000 in royalties just that year but had also found himself down to his last $21,000, while owing more than that in taxes.

Would he have turned out better without the inheritance? Maybe. Brown also left something to Albert’s elder brother Austin — royalties on a single obscure book, which added up to almost nothing — and Austin graduated just fine and got a respectable job. On the other hand, their third brother Jimmy joined a cult and killed himself, so who knows what decides which path we take.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.