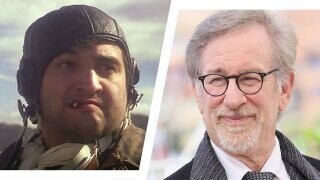

With His Comedic Misfire ‘1941,’ the Joke Was on Steven Spielberg

The early 1980s marked the end of an important Hollywood era. Throughout the 1970s, studios were letting a new generation of hotshot filmmakers take big swings on subversive, rebellious movies. This was a time when Francis Ford Coppola, Robert Altman and Martin Scorsese were coming into their own, energizing the industry with their youthful daring. But by the end of that decade, some of these auteurs’ expensive, brazenly ambitious personal projects blew up in their faces, scaring executives into focusing more on the bottom line and less on artistic risk. The movies that usually get cited — or blamed — for the downfall of the New Hollywood movement are critical and commercial debacles like Heaven’s Gate or One From the Heart. Sometimes New York, New York gets thrown in there as further proof of these “indulgent” directors letting their hubris get the best of them.

But there’s also 1941.

Don't Miss

That 1979 film, about the nutty aftermath of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, in which disparate Californians fear that the Japanese may strike the Golden State next, rarely tops lists of Steven Spielberg’s best movies. I’m not about to declare 1941 a misunderstood masterpiece, but especially as the Oscar-winning filmmaker is about to release The Fabelmans — his semi-autobiographical look at his own childhood and initial love affair with movies — it’s interesting to think that, for all the genres and styles Spielberg has tackled over the years, comedy has been the toughest for him. That was never clearer than with 1941, his first outright bomb.

It’s not like Spielberg doesn’t have a sense of humor. He had an amusing cameo in The Blues Brothers, which came out the following year. And in the widely bootlegged 1995 comedy video Your Studio and You, made by Matt Stone and Trey Parker to celebrate/poke fun at Universal Studios, Spielberg played himself as an over-enthusiastic tour guide hyping up the embarrassingly phony-looking Jaws shark that “attacks” the attendees. That said, he can be a little stiff, not someone who naturally gravitates to comedy. He’s better serving as the straight man, letting pros like Martin Short’s Jiminy Glick deliver the quips.

Which isn’t to say that there aren’t funny scenes in his movies. The original Indiana Jones trilogy has plenty of great comedic moments. But before 1941, he’d never tried to make an outright big-screen comedy. The idea for the film originated with writing partners Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale, long before they came to greater prominence with Back to the Future. As Gale recalled years later, 1941 was a war comedy based on actual events — events that wouldn’t necessarily lend themselves to a comedy.

“There were three incidents that were the impetus for it,” Gale said in 2014. “First, there was a Japanese sub that actually shelled the coast of Santa Barbara. It didn’t do any damage but the appearance of the sub precipitated two nights later the false alarm air raid over L.A. Finally, the next year saw the Zoot Suit riots in L.A. It was all of those things mixed together and the reason that it had to be a comedy was that the whole idea that for six straight hours that night in February, 1942, anti-aircraft crews were shooting up at the sky at nothing was funny — at least to our kind of warped sense of humor. We knew that if this was going to be the subject of a movie, it had to be this comedy of people misinterpreting everything in a comedy of errors with crazed people in pursuit of their goals that results in this night of total mayhem.”

At that point in his career, Spielberg could do no wrong. Making the leap from directing television to doing Jaws, which faced all kinds of production problems but ended up being a sensation, and then segueing to Close Encounters of the Third Kind, another blockbuster, this kid in his early 30s seemed to be the future of mainstream moviemaking. So doing a pricey, star-studded period war comedy was just his latest flex — one more example of the prodigy proving that he could turn anything into box-office gold.

But like those other heralded late-1970s auteurs who were setting their sights on bigger and bolder projects, indulged by studios that considered them geniuses, Spielberg went way over budget. At the time, 1941 was considered the most expensive comedy ever made. “We shot 158 days, more than 100 days over schedule,” he admitted earlier this year. “But because we were shooting back to back, the studio just started writing checks, saying ‘Let’s see what happens.’ And they gave me an unlimited ceiling to make 1941.”

It was a film that brought together stars from very different worlds. Christopher Lee, a maestro of horror movies, played an evil Nazi officer. Toshirō Mifune, perhaps the most adored of all Japanese actors because of his long association with Akira Kurosawa, had a bit part. But you also had Saturday Night Live fixtures (Dan Aykroyd, John Belushi), SCTV alums (John Candy) and Western icons (Warren Oates). Slim Pickens and Ned Beatty were in 1941, and so was Nancy Allen, who had been part of Carrie and would go on to star in more films for her husband Brian De Palma. “I have to tell you it was more fun than should be allowed on a movie,” Allen told the Los Angeles Times in 2015 about shooting 1941. “I mean really such a blast every day. … We were all hired for 14 weeks, and we were on the film for six months. If a movie had six months to shoot today, it would be normal, but then it was scandalous. ‘What are they doing over there?’”

In part, what they were doing was throwing everything at the wall to see what would stick. 1941 satirized disaster movies and war pictures. (Spielberg even tweaked Jaws by tongue-in-cheek reproducing its opening sequence — except this time, the lovely lass, played again by Susan Backlinie, gets attacked by a submarine, not a shark.) The film made extensive use of miniatures, Spielberg wanting to move away from special effects after Close Encounters. But he certainly wasn’t tired of spectacle, which is why you have scenes like a Ferris wheel being shot by a Japanese sub, and then rolling on its own.

But for all its audacious sequences and feverish energy, 1941 mostly just felt strained, its slapstick and mugging only sporadically hilarious. When the film was released in December 1979, it was derided for being overblown, self-indulgent and self-satisfied. Like those other late-1970s/early-1980s misfires, 1941 was held up as an example of this new generation of filmmakers getting too big for their britches. In his thumbs-down review, Roger Ebert wrote, “The movie finally reduces itself to an assault on our eyes and ears, a nonstop series of climaxes, screams, explosions, double-takes, sight gags and ethnic jokes that’s finally just not very funny.” Spielberg didn’t entirely disagree. In a 2011 interview, he said, “I don’t dislike the movie at all. I’m not embarrassed by it — I just think that it wasn’t funny enough.”

It’s worth pointing out that another thing 1941 shares with that Heaven’s Gate era of directorial overreach is that the movie isn’t nearly as terrible as its reputation suggests. And just as Heaven’s Gate has been reappraised over the years, 1941 has enjoyed a belated cult status, especially now that it’s available in a longer cut that allows for more character development between the comedic tomfoolery.

Even so, 1941 is the sort of big-budget comedy event in which lots of stuff happens but you feel exhausted rather than amused most of the time. Lots of comedy directors have their misfires, too, but 1941 seemed to suggest something profound about Spielberg’s limitations. He could scare audiences with Jaws. He could inspire awe with Close Encounters. But he lacked the crucial lightness needed to be funny. The madcap hijinks Zemeckis and Gale envisioned were beyond Spielberg. In that L.A. Times piece, Gale acknowledged as much. “He’s got a great sense of humor, and he pulled off some really funny bits in the film,” Gale said. “He is not the best comedy director.”

No big deal: Even the greats have their weaknesses. And certainly Spielberg has gone on to a remarkable career, winning awards for searing dramas (after people said he could only make popcorn movies) and even doing his first musical with last year’s West Side Story. But comedy still eludes him. Granted, The Terminal was a hit, even if it wasn’t all that well-reviewed. And Catch Me If You Can was a more rollicking picture from him than usual. Still, he’s never since gone as broad as he did with 1941.

Has he been tempted to give comedy another try? If he has, it appears that actress Kate Capshaw, who starred in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and married Spielberg in 1991, put the kibosh on any such aspirations. In a 2004 interview, he admitted, “My wife says I’m not funny enough! I was preparing to direct Meet the Parents when she read the script. She said, ‘You’re not directing this movie — give it to a director who does comedy well.’ She doesn’t mind when I have comic moments in my movies, like when Tom Cruise chases his eyeballs towards a drain in Minority Report, but I’m not allowed to do an outright comedy!”

This is why you should always listen to your spouse. Capshaw is exactly right: Spielberg can craft funny set pieces, but he simply seems more comfortable delivering thrills, scares, suspense and drama. The jokes are his change-up, but spectacle is his fastball. And when he tried to combine them in 1941, he crashed and burned.