5 Old-Timey Disasters America Could Easily Have Avoided

We like to look back at disasters now and then, to learn from past mistakes, or just to gawk. Today, we’re focusing our sights on one period in American history: the second half of the 19th century. This was an exciting time technologically, ushering in telephones, typewriters, cameras, and other stuff that would later all combine into the single device in your hand right now. It was also a time when seemingly reliable tech kept breaking, catching fire, and exploding, killing everyone.

Ushers Were So Scared Of Shouting “Fire” In A Crowded Theater That They Told Burning Patrons To Stay Put

On December 5, 1876, a lamp set fire to a bit of scenery at New York’s Brooklyn Theatre. Carpenters tried to simply beat the fire into submission, but this didn’t work, and the flames quickly spread to curtains and bales of straw. Clearly, act three of that night’s play would not go on as scheduled. The building was on fire, and they had to get the audience to respond appropriately. Some in the crew decided that, to avoid a panic, they should tell the audience the fire was not a problem at all.

via Wiki Commons

You’ve probably heard before of the axiom that you shouldn’t yell “fire” in a crowded theater. This is a an argument about the limits of free speech—a bad argument, we should mention; it came from a 1919 case deciding the government has the right to imprison war protesters, and this legal standard was overturned over 50 years ago and should not be cited. But whatever your thoughts about the argument, it’s not about just yelling “fire.” it’s about falsely yelling fire. At the Brooklyn Theatre that night, the fire was real, and so we got the unusual case of people in a crowded theater falsely yelling “not fire.”

Stay in your seats, said two of the actors, J. B. Studley and H. S. Murdoch. Someone in the audience (with impeccable rhythm) yelled “fire, fire, the house is on fire,” and lead actress Kate Claxton tried to counter this fearmongering. “There is no danger,” she said. “The flames are a part of the play.” A newspaper would describe this blatant lie as “bravery which those who saw her felt inspired to applaud.” However, the charade didn’t last long. A burning piece of wood then fell to Kate’s feet, and she yelled in terror.

This contradictory messaging, as with all contradictory messaging, rather than quelling panic, sparked maximum panic. The balcony audience rushed for the stairs, and many fell over and crushed each other. Some actors left by clearer exits, but some first stopped by their dressing rooms to change out of their costumes and so became trapped and died. The fire killed 278 people, making it one of the worst fires of its kind ever even today, after one in Boston and an even worse one in Chicago.

Brooklyn is also the site of our next story, which took place seven years later ...

The Brooklyn Bridge Opened Terribly

Two huge disasters hit the world this past Halloween: a deadly crowd crush in Seoul and the collapse of a footbridge in Gujarat. Those two stories together reminded us of the following one from 1883. It didn’t kill nearly as many people as either of this year’s incidents, but it will still strike you as a spectacularly needless tragedy because it resulted from a spectacularly false fear—that the Brooklyn Bridge was falling down.

The bridge officially opened on May 24, 1883. During the next few days, people crossed it warily, never quite putting their full weight down. Construction had taken more than a decade, and dozens had died in the process, including main engineer John Roebling, from infection following his foot getting smashed. Sure, a whole lot of heavy cars crossed the bridge, not to mention a hundred thousand people just on day one, but who knew when those cables would suddenly snap, sending everyone into the river.

Then came May 30, a holiday known as Decoration Day (today, we instead have Memorial Day). On the Manhattan side of the bridge, a 9-foot staircase took people down off the bridge’s pedestrian path. The crowd here pressed together thickly. Then people began screaming. Wait, there was a rush to leave? Clearly, severe danger threatened them all. The bridge had to be collapsing.

One scared mother stretched her hands out with her baby in them, asking people lower than her on the stairs to take it to safety. Then someone—identified as a “young girl” by newspapers—tripped and fell. This only made those behind her move forward more, crushing and killing her. Then they too fell, and more fell on top of them. Construction workers, still on duty at the scene, sprang in to loosen railings and make more room for everyone, but 12 people still died in the crush. Rumor quickly spread through the city of something much worse: The bridge had collapsed, people said, and 1,500 had died.

Once people knew the bridge still stood, rumors continued to call it highly snappable, even though nothing about the actual accident marked it as such. The following year, one solution to people’s distrust came from the unlikely mind of circus ringleader P.T. Barnum. With the bridge closed to traffic, he marched 21 elephants and 17 camels over it, to show its undeniable strength.

Now, do those animals, combined, weigh more or less than the many cars that cross the bridge at any moment? That doesn’t matter. What matters is the thought of the bridge supporting a herd of elephants restored people’s faith in it. We trust this was P.T. Barnum’s only motive, rather than attracting customers to his circus, because if there’s any name we associate with honesty and public service, it’s P.T. Barnum.

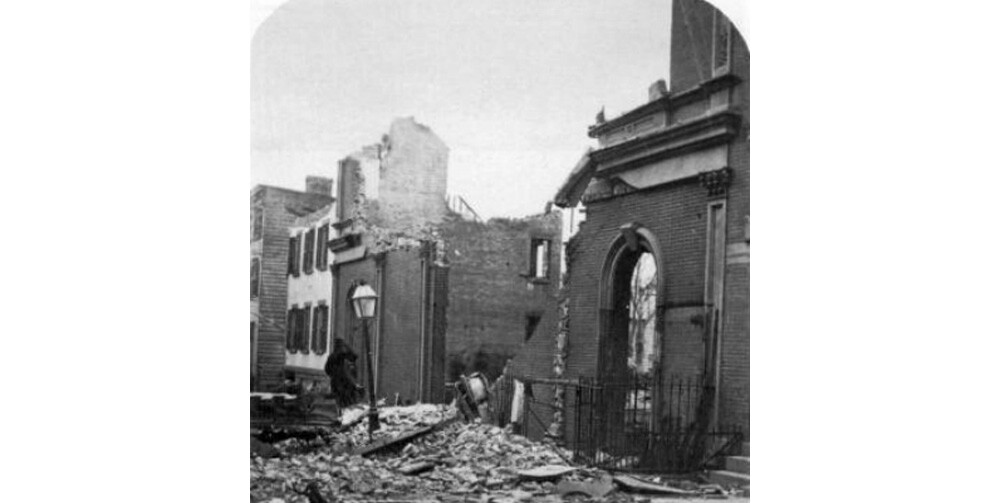

78 People Died In Pittsburgh During The Civil War ... In A Factory Explosion

The Civil War killed a whole lot of people. For example, 3,650 people died in the Battle of Antietam, and that was just one battle that took place during one day. But when reporting on that day—September 17, 1862, the deadliest day ever for American war casualties—the newspapers in Pittsburgh 100 miles away didn’t lead with the Battle of Antietam. They led with a civilian disaster from that same day because it was weirder.

The Allegheny Arsenal, in a town right next to Pittsburgh, exploded. It suffered three different explosions, which totally destroyed the lab that cranked out cartridges. We call this a civilian disaster because though the place served the war effort, the 78 workers who died were very much civilians. Female civilians, actually, including girls as young as 12.

The complex didn’t use women instead of men because men were out fighting, as factories would during World War II. No, with men all shooting each other, the factory still had plenty of available male labor in the form of boys too young to fight. But the Allegheny Arsenal had recently fired all its boys and hired girls because the boys had a nasty habit of carrying matches with them. No matter how strictly the place forbade smoking, management feared a boy might strike one of those matches and blow up the whole place. So they switched to girls, who performed matchlessly, and then one day, the whole place blew up anyway.

A century and a half later, we still don’t know what caused the explosion. If it was Confederate sabotage, you’d think Pittsburgh detectives would have produced some evidence by now (you’d think they’d have produced such evidence even if it weren’t Confederate sabotage). We only have theories about the cause, and the most accepted explanation has the advantage of also being the dumbest.

The delivery wagon spilled some gunpowder, says this theory. Someone should have swept it up, but no one did. Then the wagon’s horse stomped its foot. Its iron shoe set off a spark, this spark set the gunpowder alight, and that explosion set off further explosions. This theory, while nuts, has been deemed the most plausible, more plausible than the next competing theory: The spark came from the metal in one girl’s impractical hoop skirt.

The Chicago World’s Fair Had The Worst Fridge Ever

The 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago showed off such wonders as a moving walkway, motion pictures (via a device called the electrotachyscope), and some kind of giant wheel made by a man named Ferris. If you were not interested in inventions that consisted of something moving round and round, it also offered what they dubbed the Greatest Refrigerator on Earth.

This 33,000-square-foot pavilion was themed around cold storage. It had newfangled icemaking machines. It had chests that kept meat and dairy cool even without freezing, which was fantastic. It had an ice skating rink. Still, we personally have to withhold from it the title of Greatest Refrigerator because refrigerators are supposed to stay cold, while this building caught fire.

Scientific American

The cold storage building had a 190-foot tower with a smokestack, to belch out exhaust from all the industrial processes within. One problem: The fireproof smokestack did not extend all the way up the tower. It came 14 inches short. One other problem: The tower surrounding the smokestack was made of wood, as anything more fire-resistant would clash with the surrounding architecture. Hot smoke left the steel stack and hit woodwork. In time, inevitably, heat set the wood alight.

Firefighters climbed the tower to put out the blaze. But fire forges strange paths, and so while a bunch of men stood at the top of the tower, pointing hoses at the flames there and within, additional fires erupted at the tower’s base. The firefighters now had no clear path out of there. Some tried jumping down, and this ended poorly. Twelve firefighters died, four other people died too, and the building fell to the flames. But hey, the response did manage to save one statue of Christopher Columbus that was at risk of getting burned.

Scientific American

This fire was a huge deal at the time, beyond what the death toll might indicate, because of just how many people witnessed it. Thanks to the fair, 50,000 people watched the tower burn. One major goal of this fair had been to convince the world that Chicago was a strong city and had moved on from the Great Fire of 20 years earlier.

“Well, at least we got our quota of fires out of the way,” said one fairgoer who we just made up. Later, once the fair came to a close, other fires sprang up and burned all the vacant buildings down.

America’s Worst Sports Tragedy Sent Spectators To A Furnace

Last month, 135 fans at an Indonesian soccer game died, in a stampede made significantly worse by police attempts to control it with tear gas. Most of the world’s biggest sports tragedies occurred when fans stampeded and crushed each other, from the 1989 Hillsborough disaster to the Accra stampede in 2001 to fans falling over each other and dying in 1996 in Guatemala. America’s deadliest sports tragedy was a little different.

The year was 1900. Berkeley's and Stanford’s football teams faced off in that year’s Big Game, an annual Thanksgiving tradition. Thousands of people paid to watch the game in the stands. Hundreds of additional people without tickets just clambered onto the roof of a neighboring building.

Just a couple days ago, we were telling you about the situation in Chicago, where people sit on rooftops to watch Cubs games. The 1900 Big Game in San Francisco was not as fun a situation. The roof those spectators perched on (atop the Pacific Glass Works factory) could not support their weight.

The danger was obvious, and Stanford had actually given the plant superintendent tickets in exchange for keeping people from climbing on his roof, but people came onto the roof all the same. Unconfirmed rumors later said that the watchmen in charge of blocking all roof access instead charged for admission to the roof.

Itchy and Scratchy writers couldn’t have scripted a deadlier setup. The roof collapsed under the weight of all those people, and while a good hundred of them suffered a very painful four-story drop, some of them experienced something worse. They fell on top of one of the glass furnaces.

Yes, the factory was in operation during all this, so the furnace was running. The spectators didn't fall into the furnace, but actually, turning into glass instantly would have been more of a mercy. They instead hit the furnace's 500-degree exterior, which merely melted their skin and flesh off. Also, people smashed through fuel pipes on their way down. This fuel doused people and caught fire. Workers in the factory had to scrape the bodies off the furnace with pokers.

The game continued, uninterrupted. It’s crazy enough when a pro game perfunctorily continues, with no one really putting in an effort, after one person dies of a heart attack, but during this game, many people died horrifically, and the game continued for real, with both teams trying their hardest and continuing to score. People on the field and in the stands didn’t realize what had happened right next to the stadium. Even some newspapers that covered the game the next day didn’t mention the disaster.

Twenty-three spectators died in the roof collapse. Have you seen that comic where kids use boxes to peek in at a game without paying, with one panel captioned “equality” and one captioned “equity” (and no readers able to agree on whether the labels are correct)? That comic needs a final panel, where the kids stand on a roof. Caption: “expiry.”

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.

Top image: National Archives