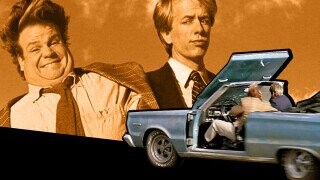

The Wild Ride of Richard’s GTX from ‘Tommy Boy’

“I’ve seen a lot of stuff in my life, but that was awesome!” Tommy Callahan exclaims after watching an angry deer destroy his friend Richard’s 1967 Plymouth GTX. They thought they’d killed the deer in question when they hit it with the car, which is why they stuffed its supposed carcass in the back seat. But later on, the deer springs back to life, totaling the GTX in the process.

That, though, was just one of the many iconic car sequences in Tommy Boy. There’s also the scene when Tommy (Chris Farley) hyperextends the GTX’s driver-side door at a gas station, and the part when the hood flies open as they’re cruising along the highway. Meanwhile, Tommy and Richard (David Spade) strengthen their bond by singing along as songs like “Superstar,” “It’s the End of the World As We Know It” and “Eres Tú” play on the car radio.

In fact, the GTX in Tommy Boy is so central to the plot of the 1995 buddy road comedy that Peter Segal, the film’s director, has spent the last several years trying to track down one of the cars he used in the movie. About a year ago, he hit paydirt, and now he’s getting the GTX restored so it can sit idle exactly where it belongs — in a museum.

Don't Miss

Below is the long, circuitous route it took for Segal — and the GTX — to get here…

‘I got a script called Billy the Third: A Midwestern. It was terrible, but it starred Chris Farley, so I had to get it.’

I first worked with Farley on an HBO special with Tom Arnold. Tom was great friends with him, and he introduced me to Farley, Ben Stiller and Jim Carrey before any of those guys really popped. I knew Farley from Saturday Night Live, but when I got to meet him, I realized he was the funniest man on the planet. I also worked with him on an episode of Tom’s show, The Jackie Thomas Show, where Farley did a cameo and brought the house down.

A few months later, I got a script called Billy the Third: A Midwestern. It was terrible, but it was starring Farley, so I had to try to get it. I met with Lorne Michaels, and he told me to meet with the writers and be honest about what I thought. Well, that wasn’t great advice because I had a few too many notes for them, and they showed me the door. But nobody else took the project, and they came back to me a few months later and said, “You’re right — the script needs a lot of work. Would you please take another crack at it?”

The original script was more like Step Brothers, where it was more about the Farley character and the Rob Lowe character. But I thought it should be more about Farley and Spade, where it’s these two guys from the factory who don’t get along but have to work together to save the factory. SNL writer Jim Downey and Fred Wolf, who was second-in-command at SNL, came out to help fix it, but the writing process didn’t go well because there was so much work to be done. Which is why I tried to quit.

I got a call from Sherry Lansing, though, and she told me that a team of lawyers was going to sue me for tens of millions of dollars. I said, “Okay, checkmate,” and I was back on the film. Years later, I ran into her while I was working on The Longest Yard with Adam Sandler. She saw me in the commissary and asked me if I remembered that conversation. I actually thanked her, because Tommy Boy is the biggest thing on my resume, and I’m grateful I did it.

‘We’ve just got to come up with funny stuff — funny stuff that’s happened to us!’

After my conversation with Sherry Lansing, I called up Fred Wolf and told him, “We’ve just got to come up with funny stuff — funny stuff that’s happened to us!” Along those lines, he mentioned one time when he was filling up his car with oil and forgot to take out the oil can and the hood flew open while he was driving on the freeway.

When we filmed that scene, the car was put onto a turntable that we’d built so it could spin around. The hood was supposed to swing up and down via a wireless receiver. But it wasn’t working that day, so the special effects guy, Warren Appleby, had to get in the trunk of the spinning car and connect the wires together when we wanted the hood to fly up. When I yelled “cut,” he’d get out of the trunk and vomit.

‘I’m sitting on the hood of the car, holding the cue cards as they’re blowing in the wind, while those two guys are singing ‘Eres Tú’’

‘You can’t train a deer’

Needless to say, I didn’t want that car back. They could have it.

For the other shots, we built an animatronic deer, which was terrible. It was worse than the Abe Lincoln exhibit at Disneyland. We used it for one shot, and it was basically just standing there. For the shot where you see its legs in the foreground with the car coming toward it, that was actually a goat. We strapped its udder to its belly so you couldn’t see it. When the deer destroys the car, that was a grip wearing a deer skin who was acting like a deer. It was very low budget, Roger Corman-esque filmmaking.

‘I spent years trying to locate one of those cars’

At the end of the shoot, they offered me one of the cars, but I thought the movie was going to tank. I had no idea what we had, so I said, “No.” But years later, I really wanted one. I spent a long time trying to locate one of those cars. My friend had an alert set up anytime one was mentioned online, and about a year ago, he found one on sale in Florida. It was supposed to go for six figures, so I called Spade and said, “Dude, I don’t have this kind of cash. You should bid on it.” He won and had it shipped back to his house. I asked him if he was going to fix it up, and he said, “No, I think I’m going to leave it in the garage, and when people come over, they can see the car.”

But then he called me up a few months later and was pissed at himself. He said, “I’m moving to a bigger place, but the garage is smaller and I sold my Chevelle and the Tommy Boy car. I should have told you about it. It’s up for auction in Arizona.” I’ve never bid on something over the phone before, so he walked me through it and I won the car. When I got it, I said, “I’m restoring this thing, and when it’s done, it’s going to the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles, so everyone can enjoy it.”

It’s in rough shape, though, so it’s going to be about an 18-month-long process to restore it. The guy working on it is posting about the progress on his blog. Either way, we’ve got about another year to go, so to be continued…