The Lost Civilization Adventures Of The Dude Who Invented The Human Cannonball

Welcome to Cracked's Actual Guide To Fake Cities – yesterday's topic: the USSR looks for a mystical city in Tibet. Today's topic: the lost kingdom of the Kalahari.

In 1885, the inventor of the Human Cannonball stumbled out of the Kalahari desert with a wild tale about a fabulous lost city, full of “cyclopean” architecture and ruined monuments. For reasons that may already be clear, these claims were completely ignored by the scholarly community of the day. But over the next century, tales of the Lost City of the Kalahari continued to haunt the region. Hundreds of expeditions were launched to find it, often at considerable risk to life and limb.

Don't Miss

Among those entranced was Elon Musk’s maternal grandfather, who took his family on yearly expeditions in search of the city. And while it may be interesting to learn that Elon’s mom had the same childhood as Sigourney Weaver’s character in Holes, there’s an even more interesting story here. So strap in, because the journey to the Lost City is a hell of a ride.

Part One: A Mysterious Diamond At The Hell Aquarium

Back in the 1880s, London’s seediest attraction was the Royal Aquarium. Originally planned as a venue for elegant cultural events, the Aquarium had first run into trouble when some poorly installed water tanks meant that it couldn’t actually display any fish. Then the public turned out to be almost aggressively uninterested in the program of highbrow exhibits meant to lure them through the doors. Facing financial ruin, the Aquarium’s owners were forced to turn to a “monster-monger” named William Leonard Hunt, who moved in his collection of circus freaks and “primitive tribesmen” and turned the place into a human zoo.

Among Hunt’s star attractions was a group of “Earthmen” from southern Africa (the more usual term is “Bushmen,” but Hunt changed it because he thought it would be funny to claim they lived inside giant anthills). These were actually San people who had been kidnapped from their home in the Kalahari Desert and taken to London, where they were kept on a small patch of sand in the Aquarium and made to dance and reenact scenes from desert life before mobs of hooting Londoners. In return, they were supposed to be given their freedom and ten goats each after six months, although it seems that they may have been stiffed on the goats. Which is all so horrifying that you probably already stopped reading and are now working on some kind of time-travelling anti-past bomb. But just in case you stuck with us, we should probably go on to say that the “Earthmen” were accompanied by a translator named Gert Louw, who eventually made Hunt a very interesting proposition.

Louw was a member of the Basters, an ethnic group originally formed by the mixed-race offspring of Dutch colonists and local Africans in 18th century South Africa (the name “Basters” means exactly what you think it does, because Dutch is a ridiculous language even when it’s being used for evil). Facing discrimination in their original homeland, the Basters migrated north to Namibia, where they founded a powerful independent republic. Louw himself was a former soldier who had fought as an ally of Britain against the Korana people, a war that ended when Louw personally captured the Korana leader Klaas Lukas. Now famed as a war hero and desert tracker, Louw had been given the contract to acquire “Earthmen” for Hunt’s zoo. He accompanied them to London as translator, but discovered that the Aquarium's owners had no intention of paying him properly. And that’s when he seems to have hatched a Plan B.

According to Hunt, Louw approached him with an uncut diamond, which he claimed to have discovered deep in the Kalahari Desert. Entranced by the mysterious stone, Hunt immediately agreed to finance an expedition in search of this fabulous untapped diamond field. Now, we should make clear right from the beginning that they did not succeed in finding any diamonds. In fact, given the mineral wealth of southern Africa, they might actually have managed to get further away from diamonds than any other humans in the region. A cynic might even suggest that Louw had made the whole thing up to secure a free ticket home and a new payday. But if so, he had picked the right mark, because Hunt was a man haunted by his past, desperately searching for some new adventure to give purpose to his life.

Part Two: The Tragedy Of The Great Farini

In 1862, 30,000 people packed into the Plaza de Toros bullfighting ring in Havana, Cuba. They were there to watch a performance by the Great Farini, the second most famous showman of the age. Farini was renowned for his daring stunts and on this occasion he had promised to cross the Plaza on a tightrope with his beloved wife Mary balanced on his back. The first crossing of the alarmingly high tightrope went off without a hitch, as did the second. But as the crowd below whooped and cheered for more, the Great Farini decided to make a third and then a fourth trip across the highwire. On the fifth crossing Mary Farini raised her hand to wave to the crowd, then lost her balance and plunged toward the ground.

The Great Farini was born William Leonard Hunt in rural Ontario and grew up in a small town that wasn’t so much sleepy as comatose. His life changed when the circus came to town, leaving the young Hunt entranced by what seemed to be a life of glamor and excitement. He spent the rest of his childhood engaged in small acts of rebellion against his strict parents, who eventually disowned him when he left home to become an acrobat, because your son doing something cool was the greatest shame the 19th century could imagine. By 1859, he had a successful career as a traveling performer in the US. But that was the year the French acrobat Blondin won worldwide fame by becoming the first man to cross Niagara Falls on a tightrope. As a local boy, Hunt took this as a personal challenge and he quickly staged his own highwire walk across the falls. The great Niagara Tightrope War had begun.

Throughout 1860, Blondin and the Great Farini competed to cross the falls in the most insane way. When Blondin carried a small man across the tightrope on his back, Hunt did the same with a local giant. Blondin had himself sewn into a burlap sack and crossed with just his feet sticking out, so Hunt shuffled across sewn in a sack that covered his feet as well. When Blondin stopped in the middle of the rope to cook an omelette, Hunt strapped a hand-cranked washing machine to his back, pulled a bucket of water up from the river, and did his laundry suspended in midair. But no matter what he did, the Great Farini found himself playing second fiddle to Blondin, who had got there first and staked his reputation as the greatest tightrope walker of the age. And while Blondin had an effortless elegance on the wire, Hunt was known for a clumsy style and numerous brushes with disaster.

And yet on that awful day in Havana, when his wife went tumbling toward the Earth, Hunt’s true talent shone through. In the split second after his wife fell, he managed to pivot and grab the edge of her dress with one hand, halting her fall. A deathly silence fell over the crowd as the rope swayed wildly, but Hunt maintained his balance and lowered himself down until he could hook his legs securely around the rope. As he reached down with his other hand to pull Mary up, there was a single moment where thirty thousand and two people thought he had done the impossible and saved her. Then the thin cloth of Mary’s dress tore and she plummeted to the ground. She died on impact, while the Great Farini had to be helped from the arena wild with grief, still clutching a scrap of fabric in one hand.

Part 3: The Adventures Of Lulu, Queen Of The Air

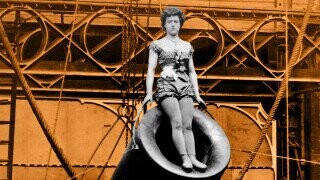

Heartbroken, Hunt largely retired from performing after his wife’s death, although he did make a brief comeback in order to support his adopted son Samuel Wasgate, who performed as “El Nino: Boy Tightrope Artist.” Instead, Hunt forged a new career for himself as a promoter and talent manager. It was during this time that he developed the human cannonball act, using a catapult to launch his daughter Lulu high into the air. He later replaced the catapult with a cannon and Lulu with a young girl named Rose Zazel, who became renowned as the first human cannonball. The act was widely condemned as unsafe, and Hunt quickly moved on to less controversial jobs, like running a human zoo.

So when Louw approached him, Hunt was rich, bored, and desperate to recapture the adventure of his youth. He also thought it would be a good chance to reconnect with his beloved daughter Lulu, whose career had been cut short by a human cannonball accident, although not in the way you’d think.

Lulu Farini made her debut in Paris in 1870, where she was billed as “the Beautiful Lulu: The Girl Aerialist.” She quickly became one of the most famous trapeze artists of the day, performing for royalty and celebrities like Lewis Carroll, who was entranced by her acrobatic feats. The press was equally admiring, acclaiming “Mademoiselle Lulu” as “the Eighth Wonder of the World.” Only the Sporting Times struck a sour note, insisting that “if Lulu the Beautiful be not El Nino Farini, there is no more truth in manhood in me than a stewed prune.”

While not very sporting about it, the Sporting Times were correct that the ironically named El Nino had transitioned to a female identity as a teenager. Now in Victorian society mentioning the word “gender” alone was enough to cause widespread swooning, so putting the word “trans” in front of it would have required the militia to evacuate the city amidst panicked rioting. As a result, the Great Farini made every effort to keep his daughter’s connection to “Samuel Wasgate” a secret. Sadly, this came to an end in Dublin in 1877, when an early version of the Human Cannonball act went awry, sending Lulu plummeting toward the ground.

Fortunately, Lulu’s life was saved by the circus’s safety net, a feature which had been introduced to public performances by none other than William Leonard Hunt after the death of his wife, when he refused to let the 11-year-old “El Nino'' perform without one. But a beautiful celebrity was in danger and half the doctors in Dublin rushed to the scene -- only to discover Lulu’s biological sex during their examination. The news subsequently made headlines across Europe, although Victorian writers were forced to use so many tangled euphemisms to describe the incident that most people probably thought they were reading an ad for a new kind of table. Lulu continued performing for several years, but her career had been reduced to a curiosity and never reached its former heights.

Lulu subsequently relocated to the US and took up a new career as a photographer. They would alternate between male and female identities for the remainder of their life, but never returned to the name “Samuel Wasgate,” preferring to be known as Lulu Farini or Lulu Wasgate. A trek through the Kalahari seemed like a good way to reconnect and the Great Farini insisted on passing through Connecticut on the way to South Africa to collect Lulu, who had agreed to come along as the expedition’s photographer. As it happened, Lulu would turn out to be a truly terrible desert photographer, but it was never going to be the most professional expedition anyway and at least it showed there wasn’t any bad blood between them after history’s first human cannonball-based outing.

Part Four: Journey To The Lost City

As we already mentioned, the Farini expedition did not discover any diamonds, possibly because their strategy of kicking at various rocks and hoping one of them would sparkle was geologically unsound. Instead, they discovered something far more valuable: friendship The Lost City Of The Kalahari!

According to a book Hunt wrote, they were journeying through a vaguely defined section of the desert when suddenly they stumbled upon "a huge walled enclosure......which looked like the Chinese Wall after an earthquake, and which proved to be the ruins of quite an extensive structure…the masonry was of a cyclopean character, here and there the gigantic square blocks still stood on the other. In the middle was a kind of pavement of long narrow square blocks fitted neatly together...in the center of which was what seemed to be a base for either a pedestal or monument." Unfortunately, the expedition’s porters refused to excavate the ruins further (the chapter of the book is literally titled “The Bastards Won’t Dig” since the porters in question were members of Gert Louw’s people and Hunt found their name hilarious).

To make matters worse, Lulu had camera trouble and failed to snap any usable photos of the site. As a result, Hunt was forced to support his story with the most irrefutable evidence of all: a poem he wrote mourning "a city once grand and sublime...swept away by the hand of time." We’d print the rest of it, but it’s so bad our lawyers think it would legally count as felony assault to inflict it on you. Sadly an expedition of carnies claiming to have discovered a conveniently undocumented lost city failed to convince the exploring community, or even sell many books, and Louw, Lulu and Hunt soon went their separate ways, never to return to the desert. But then a funny thing happened.

Beginning in the early 20th century, the story of the Lost City began to attract new attention in southern Africa and Farini’s supposed discovery soon became a local legend. By 1963, at least 26 major expeditions had been undertaken to find it, as well as hundreds more amateur attempts. The years that followed saw yet more expeditions, which in recent times have used advanced equipment like drones and satellite imaging. Seriously, the last time a wilderness was searched this thoroughly was when Moses dropped his keys on day three out of Egypt and refused to move on until somebody found them.

In reality, the Lost City of the Kalahari almost certainly does not exist. Hunt was a famous liar and the desert scrubland of the Kahalari is hardly conducive to large-scale ancient building projects. But the odd thing is, we can’t find one account of people searching for the lost city who didn’t have a really great time doing it. Maybe every region needs a crazy legend that locals can mess around in the desert hunting for. The Great Farini certainly didn’t come to the region looking for a city, or even diamonds really. He wanted to find one last adventure, and maybe he left an excuse for everyone else to go find one too.

If you can’t afford a trip to the Kalahari, why not explore the unbearable desert wasteland of Alex’s Tweets.