4 Uncommon Scenes Of Everyday Life Around The World

The term "daily life" has connotations. It's what you do every day: awaken, cry, vomit, feed the mewling pet or basement prisoner, then perform time-labor for an agglomeration that considers you a number (and not a flattering one) rather than a name. You come home, consume the vacuous fecal precipitate of Hollywood's turgescent rectum, then drift off to the only locus of true peace: the timeless void.

This routine is mostly the same everywhere, but finer details differ. So cast off the feelings of oppression, and enjoy the following candid glimpses into the worldwide world outside of our flimsy, feeble existence. My suggestion? Pair this with a beer or maybe even four or five ...

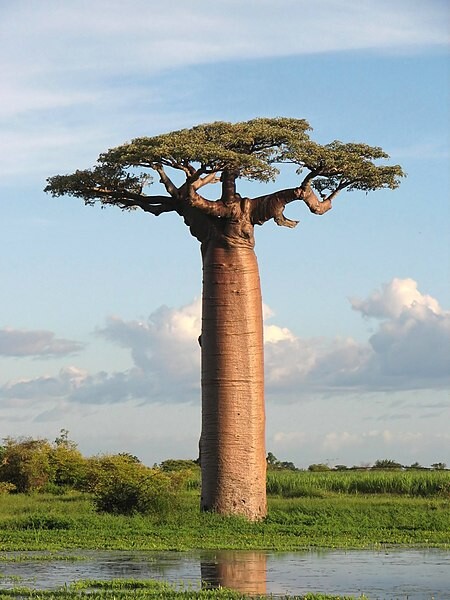

In Madagascar, People Drink From Giant Trees

Don't Miss

Depending on wealth, in ascending order, individuals get their daily hydration either from tanker trucks, lakes, taps, bottles, or by Sparta-kicking the impoverished children huddling above a puddle. The latter folks don't actually drink from said puddle, but know that trodding on the poor quenches more fully than any liquid. But on the Mahafaly plateau of Madagascar, locals get their water by hollowing out gigantic trees that are older than modern history.

Baobabs are also unique, majestic wonders that a disheveled Almighty Creator seemingly planted upside down during an early morning, federally mandated stint on a civic beautification workforce. There are nine species of baobabs in the genus Adansonia, named after French explorer-botanist Michel Adanson, who's remembered on better terms than 19th-century British naturalist Albert Hornbatter Wagsbottom Wiggins and his eponymous Wiggins Dickweed.

As mentioned, baobabs live for thousands of years. Some may have been fledged when 5-year-old Jesus was melting Hot Wheels on the stove and then chucking them out of his multi-story-apartment window—I couldn't have been the only kid to do that, right?

Baobabs also improve the soil, recycle nutrients, and provide shelter, water, and food for many animals. Baobabs also supply people with timber, fuel, medicine, building material, and numerous foods, including sprouts, the bane of Malagasy children.

And in Mahafaly, the few annual rains are immediately sucked by the porous limestone. There are no bodies of water for the 20,000 thirsty people. Fortunately, a large tree can hold 14,000 liters, the American equivalent of 500 Aikman Ounces. Each family may hollow out its own “water bottle” baobab, a process that requires three workers and ten days of hacking. This reserve may last from July until October, after which some families travel 18 hours by cart to buy water.

These are crappy conditions but relevant perspective for those of us who bemoan the couch-to-fridge commute when craving a Capri Sun. Until, for many, the prescribed opioids kick in. Then it's allll groovy, baby.

Ganvie, Benin's Venice, where everything's on stilts

Even though Ganvié is around 400 years old, it's perfectly representative of how our future cities will look if companies keep melting our glaciers and jungles into caramel colored concrete cleaner.

Ganvié is a stilt city built over Lake Nokoué in Benin, a West African nation with a somewhat phallic outline.

The "Venice of Africa" is home to 30,000 residents and 3,000 buildings upheld on rot-resistant red ebony wood. With almost every structure separated by water, daily excursions require rides in narrow boats called pirogues.

The aqueous erections of Ganvié were established by the Tofinu people, for evasive reasons, circa the 16th-17th centuries. Around this time, the Fon people of the former Dahomey Kingdom were raiding and capturing nearby groups to sell to Portuguese slavers—it turns out that da homies of Dahomey were definitely not homies.

But the Fon couldn't tread on water due to religious, demon-based reasons—inverse Jesus logic. So the Tofinu built their sanctuary on the lake and named it Ganvié, meaning "We survived ."

Tourism is quickly becoming Ganvié's main industry, but it receives around 10,000 visitors per year and doesn't suffer the plagues of Venice and Europe's other floating stereotypes. It does not yet smell of urine, and its waterways and canals are not yet clogged by sanitary pads and short-rib bones from flocks of Chinese tourists.

Still, pollution, overfishing, and lack of a sewage system threaten Ganvié's future, as dumped feces circulates among the fish that become dinner. Sure, it's no Ganges, but it's not ideal.

Ashgabat, Where Everything (Including Your Car) Is White

In Turkmenistan, completely unlike in the U.S. of Goddamn MFin' A, baby, the people suffer in barren bareness while the "elites" lavish in marmoreal magnificence. Its capital city, Ashgabat, is a dictatorial premature ejaculation with wide boulevards, immaculate streets free from riff-raff, and grand structures of Italian marble—it's what I imagine Elton John's house looks like, minus the rainbow unicorn triumphal arch.

T-stan's structures aren't just grand; they're the world's grandest. In 2013, Guinness World Record officials sporting new, gem-encrusted watches engraved with “Turkmenistan is the world’s excellent paragon,” declared this modern dystopia the marble-iest place in the world. No physical locale boasts as many marble-clad buildings as Ashgabat, which harbors "543 in an area of 4.5m square metres." This central Asian capital city also houses the world's largest indoor Ferris wheel, built at the cost of more than $60 million, which the goitered residents would have otherwise wasted on grain and iodine.

And check out the groovy Wedding Palace, a lovechild of The Eye of Sauron and an ABBA concert:

In fact, Turkmenistan is racking up Guinness World Records at a Guinness-World-Record rate. It has swiped the much-coveted "largest cycling parade on one line" and "world's First plant for the production of gasoline from natural gas" from beneath our very noses. Yet the cowardly, cowing far-wing media remain suspiciously hush about these breaches of global ethics.

What’s up with that? Turkmenistan only basically had two rulers since its 1991 split from the dissolved Soviet Union. A third ruler took over earlier this year, but he's the second ruler's son. And these rulers were as autocratic as is expected from a gas-rich "-stan."

Turkmenistan is a global top-five in terms of natural gas, which funded its marble transformation. Unfortunately, apparently, not many people enjoy this "city of the dead," where streets harbor cleaners, officials killing stray dogs (and sometimes not-so-stray dogs), and no other people.

The regular folks have been pushed to the city's outskirts to reside in tiny apartments with uncertain water supply. Though the revamped international airport was pimped to the tune of £1.7 billion and only sees 10% of its intended "1,600 passengers per hour." But at least it's "foreboding," which is what you want when welcoming hesitant tourists with a tenuous visa.

And even though Ashgabat is clad in white and gold, your car can be any color. If it's white. Imports are limited to white autos, and all features like grilles must be painted thusly, as police demand bribes or impound the vehicles of non-conformers. Though the official argument is that the white repels the intense desert sun rather than, you know, dystopia.

People in Meghalaya people deal with rain every day

Fantasy and sci-fi have an eternal boner for elven tree cities, Tatooine, and cramped Tokyo-scapes. So if you've grown tired of pointy-eared archers, space bedouins, and neon sprawl, check out a real fantasy setting: Meghalaya, where it rains pretty much every day and the architecture is alive:

That's one of Meghalaya's many living root bridges, a solution for traditional structures that decay in the daily moisture. People here wear rain-repelling bamboo apparel, getting into bed is "like crawling into an old kitchen sponge," and visibility (especially while driving) is often limited to several feet:

When rains and winds combine, they unleash otherworldly tempests that whip waterfalls into opaque clouds of Poseidonic fury.

Why such heavy downpours? As summer currents rollick northwardly over the steaming plains, they gather moisture. Then the currents hit the steep Meghalayan hills and get squeezed through gaps, compressing them until they, meteorologically speaking, bust a big ol' nut. They bust this big ol' nut across Meghalaya’s midriff but especially on the villages of Mawsynram and Cherrapunji, which have become the world's rainiest residences.

The resulting rainfalls are nigh-unbelievable. In June 2022, Cherrapunji received 38 inches in just 24 hours, though that prodigious pouring is nowhere close to the record of the 61.5 inches that fell on June 16, 1995.

And as a sign of coming times, or an evil-genie-wish scenario, even this rainiest of places is subject to water shortages during the latter, non-monsoon months. Due to poor water and land management, inadequate storage capabilities, soil erosion, and other stuff, the world's rainiest residents are buying water to survive.

On the plus side, they do get to wear these sweet Ninja Turtle shell-looking rain shields.

Thumbnail: jbdodane/Wiki Commons - CC/BY/2.0, Jayesh minde/Wiki Commons - CC/BY-SA/4.0