6 Fantastical Animals We Drove To Extinction

A couple weeks ago, we shared with you a weird bit of knowledge: Avocados evolved those huge seeds so extinct megafauna could eat and spread them. A number of readers then reached out to us, saying we’d got them newly interested in these mysterious extinct creatures. The previous sentence is 100 percent true (zero is a number).

So today, we’re going to take a closer look at these huge dead beasts. Not just because of avocados, no. You don’t need to be interested in any specific food to drop your jaw at the sight of ...

Glyptodon, The Car-Sized Armadillo

Don't Miss

Below is an armadillo. It is quite small.

They can get larger than that. The giant armadillo, from South America, can weigh 60 pounds. But if we turn the clock back 10,000 years, we come upon a variant that weighed two tons. This was the glyptodon, a creature the size of a small car. A thousand bony plates protected its body, and it wielded a weaponized tail that mates found super sexy.

The glyptodon returned to scientific attention recently thanks to a bit of scholarship tracking how intelligence helped animals escape extinction. The bigger the brains, said this research, the better chance they had, and the giant glyptodon had a disproportionately very small brain.

That sort of scientific conclusion might leave you saying, “Well, duh. Of course a brain’s an advantage. Now, if you had a study proving that bigger-brained animals were more likely to die out, that would be worth talking about.” And you might even think of plenty of exceptions to the rule, including durable animals with no brains at all. The conclusion’s interesting though because of just how long these pea-brained mechadillos lasted until their dumbness finally proved their undoing. They sprang up some 23 million years ago, and they managed just fine without any of your fancy book learning. Then humans came, and a fair number of animals were smart enough to evade us, but not the glyptodon.

It couldn’t have helped that glyptodons had a condition known as rod monochromacy. Thanks to the kind of cells they had in their eyes, they could see okay in dim conditions, but in bright light, they went blind. They therefore had to die, as a punishment for crimes against logic itself.

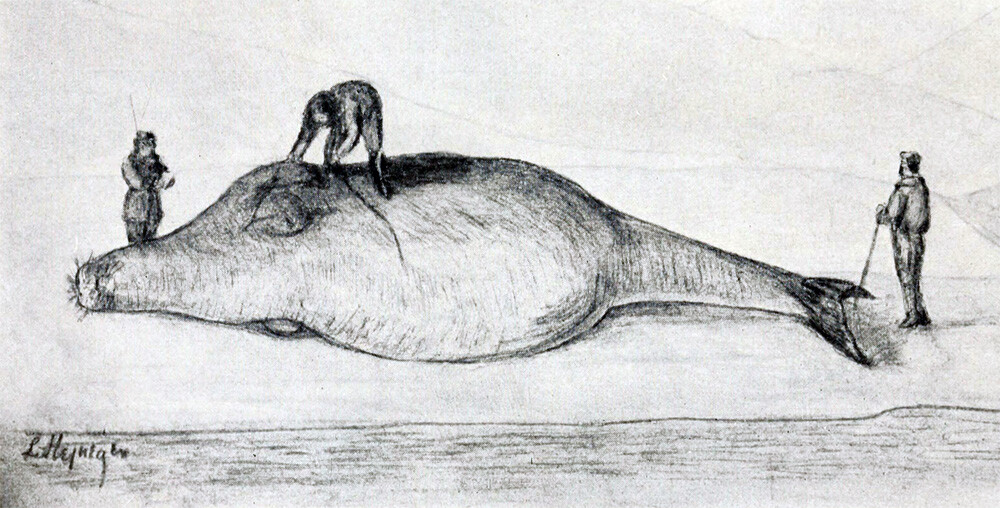

Steller's Sea Cow

Manatees are pretty big and pretty weird in their own way, probably creatures who slipped out of another time or another world. But just a few centuries ago, they had a giant relative, a sea cow measuring 30 feet and weighing 10 tons. We call it Steller’s sea cow after Georg Steller, a man who also lent his name to the Steller sea lion, Steller's sea eagle, Steller's jay, Steller's eider, and an ornamental plant called Artemisia stelleriana (but more commonly known as hoary mugwort).

Steller came upon his sea cow during an 1741 voyage to Alaska. His whole crew was sick with scurvy, save for Steller himself, thanks to his habit of nibbling herbs. He landed on an uncharted island full of foxes that showed no fear of him at all. Then he spotted the sea cow, huge, slow, and quite delicious. The cows made for easy prey, and their fat tasted like Dutch butter.

The people who hunted the sea cows in the years that followed (Russians, mostly) found them even easier targets than Steller had. When you harpooned one sea cow, the others didn’t flee, like so many animals who’ve adapted well to predators. Instead, other sea cows would swarm the wounded one, cuddling it, so hunters could slay the whole lot of them. For a while, hunters found no shortage of Steller’s sea cows. Then, suddenly, the numbers plummeted. They sighted the last specimen in 1768, less than 30 years after they spotted the first one.

Looking back, that’s surprising because it happened so quickly. At the time, it was even more surprising because people did not previously believe animals could become extinct at all. In hindsight, we know of species who died out in modern times before this, but they hadn’t figured that out yet—all animals had existed since Creation, they thought, and always would exist. The ocean, especially, held endless bounty, with all stocks replenishing through mystic sea magic. Discovering that was untrue meant a rude awakening, and people had to rethink how to source their Dutch butter thenceforth.

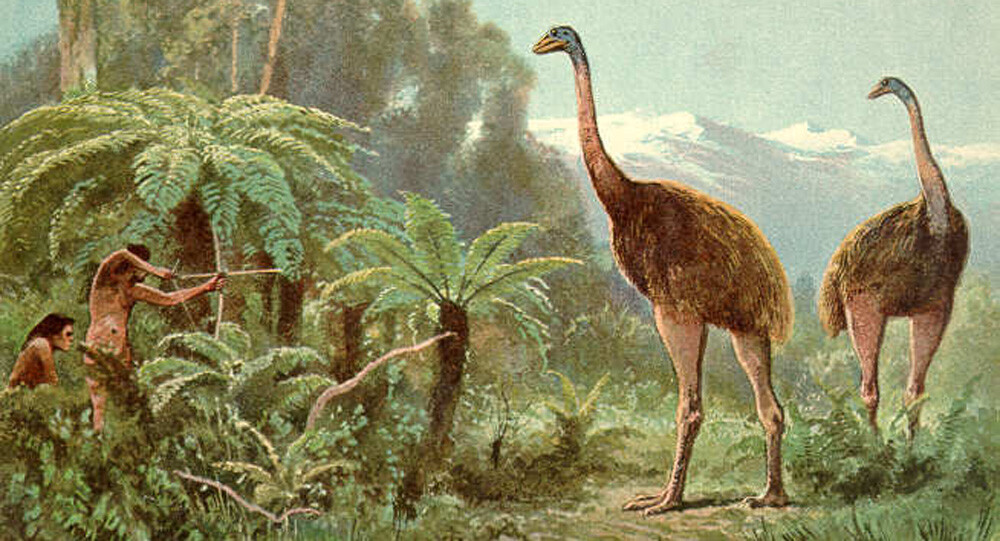

The Moa

Moa were big big birds, and they survived long after prehistoric times. As recently as the 1800s, possibly—that’s when we had the last unconfirmed sightings of the moa—12-foot-tall, 500-pound birds stomped around New Zealand. Ostriches are pretty big but not as big as the moa, whose only natural predators were an ancient giant eagle and the snuffleupagus.

Today, we’ve told you about a few animals that died out due to humans hunting them. With the moa, however, we have a bit of a twist: The moa died out due to humans hunting them.

Seriously, this was a twist for the scientific community. For years, competing theories explained why the moa, which had inhabited New Zealand for 60 million years, died out in a matter of centuries or quicker. Maybe volcanos doomed them, suggested some, or maybe they caught the flu. Then scientists from the University of Copenhagen studied the DNA from moa samples spanning 4,000 years. If bird numbers dwindled thanks to pre-human disease or gas attacks, we should see signs of similar earlier triggers affecting their genetic diversity. No such signs exist. Instead, we just see their population collapsing with the arrival of humans 600 years ago.

The people who arrived in Polynesia those centuries ago are what we now call indigenous, and yet these scientists point out that the Earth with its massive history laughs at such distinctions. All humans are equally new and weird to ancient creatures. And indigenous peoples didn’t really live in harmony with nature, say the scientists. They dominated the land as much as they could. The only people who live in harmony with nature are hippies, whom scientists do not classify as human.

The Other Mammoths, As Cool As The Woolly Ones

The woolly mammoth gets all the fame, and all the money. When we hear “mammoth,” we think of woolly mammoths hanging with giants in the snows of Skryim. We think of woolly mammoths hanging with giants north of the Wall in Westeros. We think, “Huh, those two settings were kind of similar, what’s the deal with that?”

But while the woolly mammoths were the last to remain, the only ones still alive when the pyramids went up, spare a thought for all those other crazy species of mammoth, most of which were bigger than the woolly ones. If you’re wondering which mammoths are famously depicted in the La Brea Tar Pits, that wouldn’t be the woolly mammoth, since Los Angeles isn’t known for its snowy climate. It’s the Columbian mammoth, named for Christopher Columbus.

Ryan Menezes

The Southern mammoth lived in Central Asia and Europe. That may not sound very southern to you, but that’s because you don’t live in London.

The pygmy mammoth had a ridiculous name, as ridiculous as jumbo shrimp. It may have weighed just a single ton, a tenth of the Columbian mammoth.

The steppe mammoth lived in Mongolia 33,000 years ago, but it started out two million years ago. We’ve extracted some million-year-old DNA from steppe mammoth samples—that’s the oldest DNA we have, of any kind.

Did humans hunt mammoths into extinction? Some mammoths, sure. For example, a little north of Mexico City, scientists discovered pits into which ancient humans trapped mammoths. One skull showed spear marks, confirming that humans didn’t just scare the beasts in using torches but engaged in in duels. Maybe they also made tools out of the skeletons: The pit contained remains from 14 mammoths, and in every skeleton, the left shoulder blade is missing. Plenty of right blades but no left ones. We don’t know what people did with the left bits, but they must have done something.

Let’s veer a little though now and tell you about some that didn’t die thanks to humans. The last mammoths in North America (these were woolly ones) lived in Alaska 7,000 years ago. They hung around on the land bridge to Russia, which became Saint Paul Island when the sea rose. And so they got cut off, stranded in an area the size of a city.

They lasted thousands of years there while all the other American mammoths died out. But then they too died out ... from thirst. Yes, they stood free from most threats on their Lost World island, but sea water flowed into some lakes, and other lakes dried up. The mammoths were partly to blame for this, say scientists. They hastened the lakes’ destruction by messing with the environment, making them guilty of mammoth-made climate change.

The 7-Foot Beaver

We mostly choose which topics to cover based on which phrases we can’t say with a straight face. For that reason, we proudly share with you Castoroides, the 7-foot, 250-pound beaver. Here’s is a painting showing some of these huge beavers from New Jersey:

Castoroides, as big as a bear, existed alongside humans. One cave in Ohio, a site going back to the Ice Age, contains giant beaver bones next to human artifacts from the ancient Clovis people, including spear points. We believe this was a human cave where they stored animal remains, rather than a beaver cave where they stored human trophies, only because the cave also contained human excrement. Yes, actual human poop from 10,000 years ago, preserved by the cold. Archaeologists refer to these samples as “paleofeces,” to make it sound more exotic when they get excited over digging through people’s turds.

“I'm sick of your shit, Jones. Just show me the cool skeleton of the giant beaver.”

Since humans and Castoroides lived at the same time (let’s avoid using the word “coexisted,” since humans hunted the beavers, possibly to extinction), record of the beast shows up in oral tradition. Legend tells of an ancient giant beaver who built a dam so big that it flooded the whole land. So the hero Glooscap smashed the dam, returning access to the grounds but also creating the Great Lakes. In some versions of the story, he does this when whales ask his help. Some archaeologists dispute either story as a historical account.

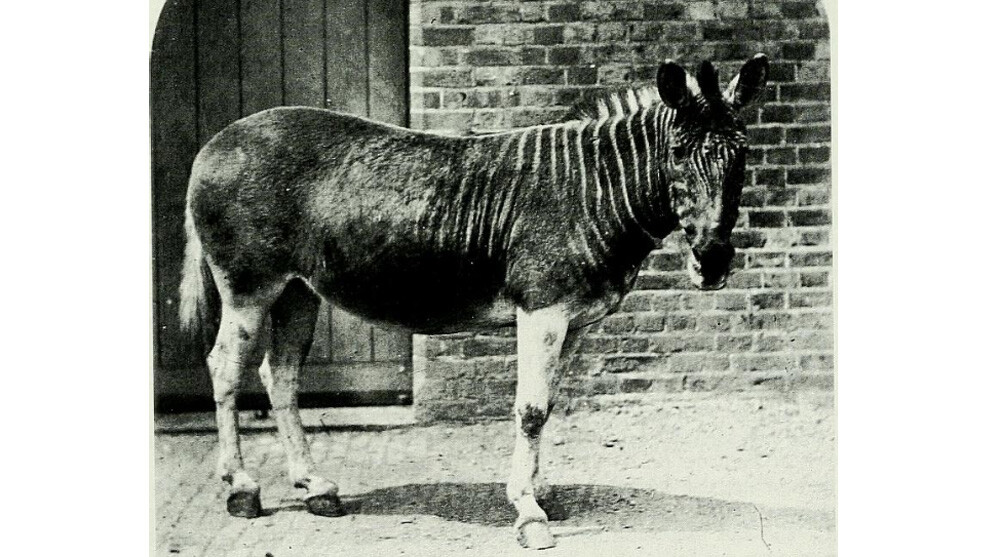

This Zebra That We Stopped Drawing Because We Got Lazy

Look at this thing. This can’t be real, can it?

That looks like someone was told to imagine the offspring of a zebra and a horse but didn’t know that hybrids generally don’t look like two halves clumsily glued together. But it's a real animal all right. It's a quagga, a type of zebra last seen in the 19th century. While we only have photos of one specimen, a mare kept at the London zoo, we have preserved skins as further evidence of the species' strange appearance.

The name “quagga” might not sound like any other animal represented in the English language, but you could say the same for “zebra.” Both are useful Scrabble words anyway, and quagga is the word that the Khoekhoe of Southern Africa came up with for the animal. We have records of the animal from prehistoric times through cave art, and by the middle of the 19th century, numbers had fallen hard. The same London zoo that kept that mare brought a quagga stallion in hopes of breeding the species, but the stallion ran into a wall and died. It mourned losing its freedom so much that it killed itself, people said—though, this is just speculation, and this quagga may also just have been really stupid.

The last quagga died in captivity in 1883, having lasted there for over 20 years (not all quagga chose death over bondage). And that was the end of the story of the quagga.

Till now. Because a group of mad scientists have decided to bring the quagga back to life. And in fact, they’ve already succeeded. Behold!

Okay, they haven’t exactly resurrected a dead species. This group instead bred existing zebras to bring out characteristics similar to the extinct quagga, creating a breed similarly deficient in rear stripes. They are phenotypically similar to quagga, the scientists proudly proclaim—which just means they share characteristics with the quagga but not that they share genes with them. It’s unclear what advantage these new zebra (dubbed “Rau quaggas” after extinct project founder Reinhold Rau) have over their fully striped brethren. They may instead suffer from several disadvantages.

“You can try and do something or you could just not,” says current group leader Mike Gregor, defending the project’s aims. You might say that there’s one additional question that the scientists should have asked themselves.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.

Top image: Heinrich Harder