A Brief Timeline Of The Wristwatch

In an increasingly busy modern world, the passage of time, perhaps to the detriment of our collective stress levels, is something that has to be constantly monitored. Whether it’s meetings to make, waking up for the workday, or or just hurrying to catch the end of happy hour, the tick-tock of the global clock is displayed and observed all around us to keep us little meat suits moving smoothly. One of the quickest ways to know the time is to strap it directly to your wrist, and the wristwatch is a piece of technology that still remains relevant for everything from timing military movements to accessorizing a sharp suit.

So when, exactly, was the watch born, at first from the marriage of clock and pocket? Let’s take a trip back in time (I promise to minimize the puns here) and see the journey of the watch from theory to wrist.

Time (Plus) Travel

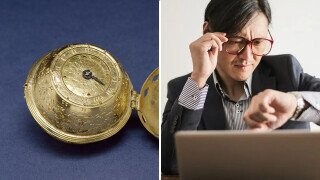

The very first watches look more like a puzzle that opens a portal to a plane of pain and pleasure when solved, but they indeed do tell time. Not very well, mind you. Given the era, we can’t be overly critical, but the estimated accuracy was within the margin of error of a full half-hour. So basically, It could just tell you what 48th of the day it was. Still, we’re talking about the early 16th century. People were still figuring out what was on the other side of that big blue wet thing.

Another fun fact: these early, often spherical watches (sometimes called Nuremberg Eggs) were most often worn around the neck. Meaning maybe Flavor Flav’s famous watch necklace wasn’t an outlandish fashion choice, but simply a tribute to the history of time-telling itself. A strong maybe.

Watch Meets Wrist

The first watch to be considered an ancestor of the modern “wristwatch” was a gift given to Queen Elizabeth I. It was described as an “armed watch”. The fact that it was a gift given to the Queen tracks with two other facts about the trajectory of the watch: first, that they were, for a long time, more novelty than tool, due to their inaccuracy. The second was that wristwatches would be, for centuries, considered a women’s accessory, men much favoring a watch worn around the neck or tucked into a pocket.

Measuring Minutes

A massive technological jump occurred in 1657, when a Dutch scientist named Christiaan Huygens invented the balance spring. The balance spring was a hair-thin spring that helped regulate the movement of the balance wheel, which is a small weighted wheel that basically (don’t @ me, horologists) serves the purpose of a pendulum in a watch. The balance spring helped these wheels spin at a much more reliable frequency that wasn’t as affected by movement or outside forces, and made them much more accurate.

Watches suddenly jumped from being basically hour estimators to being reliably able to keep time within 10 minutes. The balance spring is also pretty much responsible for the addition of a minute hand to the watch, as adding one to previous watches wouldn’t have been much more than a visual decoration. Now, though, the minutes hand was somewhat reliable. If you need to know just how brilliant an addition the balance spring is, know that you can still find them many mechanical watches off the shelf today.

Clocks Begin To Tick-Tock

In 1759, an Englishman named Thomas Mudge invented a device that greatly improved both the accuracy and reliability of the watch, the lever escapement. Without an escapement, the balance wheel we mentioned earlier was constantly in contact with the rest of the watch’s movement. The lever escapement let the balance wheel swing much more freely, only pulling power in short increments to advance the hands.

Though many of us haven’t opened up a modern mechanical watch, either in person or vicariously through a YouTube video, you’re likely already aware of the existence of the lever escapement. That’s because the lever escapement is the mechanism responsible for the “ticking” sound of a mechanical watch. Pop open one of those YouTube videos and you’ll still see watchmakers removing a version of the lever escapement, complete with pallet fork, today.

Mass Manafacture

If you’re setting out to buy a watch today, the levels and variance in cost are so widespread as to make “how much do you want to spend” often one of the first questions asked to a watch-seeker. Part of that can be attributed to the quartz watch (more on that later), but also to revolutions in manufacturing. One of the very first companies to produce watches using mass manufacturing and interchangeable parts was the Waltham Watch Company, founded in Massachusetts in 1851. Watches were now an affordable tool, not just a luxury.

The Watch As A War Machine

In the late 1800s, wristwatches remained squarely in the realm of women’s fashion, but their convenience and utility was realized in wartime. As military tactics became more advanced, the ability to synchronize troop movements silently and independently offered huge benefits. The British Army would begin to use wristwatches during the First Boer War, and the value was quickly confirmed. By 1900, wristwatches were being designed for specific military use, and even being issued to soldiers, a tradition that would continue. Some of these military-issue watches are prized collector items today. If you want to make your wallet sweat, look up the modern prices of the Rolex MilSub (Military Submariner).

Pilot Watches Take Off

Another use-case for the wristwatch presented itself in the world of aviation. A famous Brazilian aviator named Alberto Santos-Dumont found himself in a pickle, where a watch sitting in a pocket is all but useless while actively piloting an aircraft. He wanted a watch that could be easily observed without taking his hands off the controls. Luckily, he had a friend that was able to develop a watch for him: Louis Cartier. Yes, that Cartier. In fact, though it’s noticeably less rough-and-tumble, the Cartier Santos, named for him, is still a cornerstone of the Cartier catalog.

World War 1 Watch Boom

Nothing can move an accessory more quickly into the realm of the macho than labeling it as “tactical,” and that’s exactly what pushed the wristwatch into the realm of man-approved wear. The wristwatch, now that it had been widely adopted as a military tool, was present on the wrists of many of the service members of World War 1. Upon their return, civilian men finally took to the trend, and it was in the years following that wristwatches would become an essential men’s accessory.

First Self-Winding Watch

Mechanical watches, for much of history, including many models today, require winding. First, with a key, and later, through the operation of the crown, the small nubbin on the side of most watches. Attempts to create a watch that wound itself continued throughout almost the entire lifetime of the watch, but the most success was achieved in 1923 by John Harwood, an English watch repairman. It used an internal weight that swung with the natural day-to-day movements of the wearer, winding the watch without any input. His weight sat inside the watch, bouncing off two internal bumpers, resulting in this design being referred to as a “bumper” watch.

His design would be improved by a fairly recognizable Swiss company named Rolex in 1930, which used a weight that swung freely 360 degrees, and resulted in a still-respectable 35 hours of power from each wear. It debuted in the Rolex Oyster Perpetual, inspiring the “perpetual” in the name. Self-winding movements are the basis of most high-end mechanical watches today, though often referred to as “automatic” movements.

The Quartz Crisis

In 1969, the absolute nicest of years, Japanese watch manufacturer Seiko introduced a technology that would revolutionize the wristwatch, and in one fell swoop, almost bring the Swiss mechanical watch industry to its knees. This was the introduction of the quartz watch. Released on Christmas Day, it was one of the worst gifts the world’s mechanical watch makers would ever receive.

The Seiko Quartz Astron, instead of relying on mechanical balance wheels, used the oscillations caused by running electric current through quartz. This created a watch which was not only much cheaper, but much more accurate than a traditional mechanical watch. The only practical downside being the need for a battery, and battery replacements. For these reasons, the quartz watch would quickly completely take over the wristwatch market, and remain the king. The next few decades saw some storied, but stubborn Swiss watchmakers completely fold due to their resistance to produce quartz watches.

The quartz watch still holds a commanding control over the entirety of the affordable end of the watch spectrum, and is what likely occupies the wrist of any casual watch owner. A renewed interest in mechanical watches has emerged as of late, but quartz is forever part of the landscape.

Top Image: Walters Art Museum/Pexels