5 Secrets Of Everyday Foods That Go Back Thousands Of Years

It’s fascinating to look back through history to see why we humans ended up eating the food we do. You come upon such explanations as “a company exec thought of it,” “an advertising exec thought of it,” “a marketing exec thought of it,” and—of course—“war.”

Today, though, we’d like to go even further back in time. Way back, uncovering that ...

We Drank Milk For Thousands Of Years Before Evolving The Ability To Digest It

We’re going to start by telling you a story about milk and genes, a story you might have heard before. Then we’re going to tell you that, whoops, that story isn’t true. The truth is weirder.

Don't Miss

Here’s the story. Most mammals can only digest dairy while they’re babies. Once weaning ends, the ability to digest lactose vanishes—no animals drink milk after this point, so evolution never favored the ability to digest milk during adulthood. Humans are an exception. Humans too started out mostly unable to digest milk as adults ("lactase non-persistent"), but then some people spontaneously got a mutation that let them overcome this, and they made good use of it. Milk-drinkers gained a huge advantage, since they had a new food source, and so natural selection favored this gene. Though a huge chunk of the world population is lactose intolerant today, lactase persistence spread widely in Europe, thanks to how early and how widely they domesticated cows.

That story sounds like it makes sense. We’ve previously told it to you, and scientists believed it was true for decades. But when it comes to genes, a lot of the most popular stories are intuitive ideas that demonstrate how evolution works instead of anything we really know happened. That's also why, for example, schools teaching basic genetics were telling kids genes determine hair color long before scientists identified any genes that did this. Then, when scientists did start identifying hair color genes, they found the truth a lot more complicated than schools ever taught.

Last month, a mighty coalition of scientists—a coalition so big, they couldn’t even fit their names on the front page of the paper—completed a research project on that whole milk gene hypothesis. They tracked how long humans have been eating dairy by analyzing dairy traces on bits of pottery spanning thousands of years. And then they tracked the rise of the lactase gene (catchily named “rs4988235-A”) by digging into DNA from human remains spanning thousands of years.

They found that as early as 5500 B.C, ancient Europeans were eating plenty of dairy, and rs4988235-A was making its first rare appearances. And then, over the course of the next 3,000 years, that gene variant, which was theoretically so useful ... didn’t spread at all. It remained just as rare. The vast majority of people lacked any ability to digest dairy, but everyone went on eating it just the same. “This cheese is too good to give up,” they said, blasting noisy diarrhea, for millennium after millennium.

We used to tell each other that lactase persistence offered a large evolutionary advantage, but it apparently did not. Maybe this was for the same reason that lactase persistence offers no boost to your life expectancy today. Ever since we invented society, if you can’t eat one food, you have a good shot of getting a substitute that suits you just fine.

Rs4988235-A must have offered an advantage eventually, else it never would have become so common, but it offered none under normal conditions, for thousands of years. Maybe it became useful during some famine or plague. That yogurty diarrhea, which most people happily experienced every day, suddenly became deadly, leaving the lucky few who ate cheese without their bowels exploding to survive and raise cheese eaters of their own.

We Domesticated Chickens For 7,500 Years Before We Figured Out Eating Them

Truly, this is an underreported duty of archaeologists: Finding out when people added new selections to their menus. Take chicken. Israeli scientists, reviewing some of the most analyzed archaeological sites in the world, have found the oldest evidence of humans raising chickens for meat. This goes back to the fourth century B.C. That’s older than previous estimates but still not too long ago at all.

Now that you think about it, have you ever previously heard about people back then eating chicken? Probably not. In fact, uh, some of you haven't heard much of anything specific about what people ate back then, but think back to what stories you have heard. Take the Bible, which is full of talk of people slaughtering lambs, goats, and fatted calves. Notice what no one eats in the Bible? Chicken. There are special rules if you’re thinking of eating a camel or a badger, or a vulture or an ostrich, but no mention of eating chicken. (Which means we can assume chicken's not unclean, but still, no one in the Bible goes and eats one.)

If you insist on sources more historical than the Bible for some reason, you’ll find the date of chicken dinner’s debut even more surprising because we actually have plenty of evidence of chicken domestication in ancient times. The chicken is a domesticated variant of wild junglefowl, and we have pictures of chickens (not junglefowl) on pottery from centuries before this recorded chicken eating. And if we turn our eyes to China, we have evidence of domesticated chickens from 10,000 years ago.

But those chickens weren’t being eaten. Well, some were eaten, presumably, but most weren’t, and they weren’t being bred for their meat. Instead, for thousands of years, we raised chickens for ... cockfighting. The beaks and claws, today the most useless parts of the bird since they’re inedible, were the first parts we noted were useful. Rather than eat cock, we pitted one bird against another, in one of the world’s oldest spectator sports. We even outfitted chickens to accompany soldiers in battle but did not eat them afterward, because frying comrades is frowned upon.

It took millennia for one man to unlock chicken’s true potential. His name was Harland Sanders, and he died to save us all.

The Goats Who Danced And Taught Us To Drink Coffee

Now, we’re again going to tell you an origin story before revealing that it’s not actually true.

This one goes back to ninth-century Ethiopia. No one yet drank coffee, but the coffee plant did exist, growing wildly and bearing berries. Goats fed on these bushes, and unlike any humans who sampled the berries, the goats also chewed and swallowed the seeds, the parts that we today call “coffee beans.”

A goatherder named Kaldi observed his flock dancing and hopping after one of these meals. Kaldi tried following their example and experienced his first hit of caffeine. He brought the discovery down to the village ... where the local monks quickly condemned him for spreading what was clearly the devil’s work. They seized the coffee stuff he carried and ordered it all burned.

When the flames flicked those beans, the smoke smelled amazing, far better than the bitter seeds had tasted. So the monks changed their mind, and they now gathered some of the burned stuff and trapped it in water to preserve the smell. This worked better than they could have predicted, and the resulting mixture formed a delicious drink.

At some point while reading that, you might have realized that this doesn’t sound like a credible account of something that really happened. Maybe it was the point when, before even starting the story, we said “it’s not actually true.” The truth is, Kaldi and His Goats is just a legend, and we don’t know exactly when or how humans started making coffee.

But we do know it took a lot of trial and error, based on evidence we have of prior attempts to eat that bush. Before humans ever made the beverage we call coffee, they made coffee protein bars by mashing the berries and mixing them with animal fats. Maybe less surprisingly, we started out by making drinks out of the fruit rather than out of the roasted seeds. We’ve been making beverages out of bitter fruit for a very long time, you see. In fact ...

We Can Track The Rise Of Alcohol To Our Evolution As Primates

Humans have been making alcohol for quite a while, maybe even for 9,000 years. We’ve been drinking alcohol much longer than that, however. The first time anyone drank alcohol was when some ancient ancestor of humans picked up a fruit that had naturally fermented. They ate it, immediately spat it out, then ate some more, because it might have tasted foul but they liked what it was doing to them.

That drunk trailblazer must have been intoxicated for a long time. Alcohol breaks down in the body thanks to an enzyme (alcohol dehydrogenase), and our earliest ancestors couldn’t make this enzyme, or at least couldn’t make the efficient variant we have today. That efficient enzyme had no use in a world without regular drinking. Once people did start drinking, it offered a significant advantage and spread widely, since whoever had it generally outperformed competitors at beer pong.

So, just how far back did we evolve the relevant gene? This diagram should clear the matter up:

If you’re one of our few readers having trouble understanding a diagram so self-explanatory, let’s just give you the answer: We evolved it 10 to 20 million years ago. For a long time, scientists assumed we evolved it when we first developed brewing (shortly before recorded history), but new research pushes the rise of this gene much further back, all the way to when our ancestors and the orangutan’s ancestors first split from each other on the evolutionary tree.

This was also when our ancestors first split from actual trees. Fruit fell, hit bacteria on the ground, and rotted, creating alcohol, and when we came down from trees, we ran into these treats. Based on the genetic record, we started regularly drinking this toxic but extremely fun substance the very moment we encountered it.

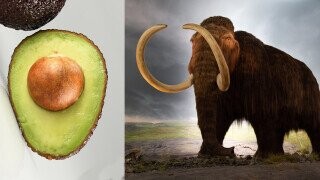

Avocados Are So Huge Because Giants Swallowed Them

Fruit really is pretty cool, isn’t it? You may think wild berries don’t taste as good as, say, ham, but we carnivores evolved a taste for ham to recognize the nutrition present in meat, despite pigs not wanting us to eat them. Fruit, on the other hand, evolved to cater to our tastes, becoming more tasty because it wants to be in your mouth. Fruits contain seeds. The tastier the fruit, the more likely animals are to eat the seeds then defecate them somewhere distant, spreading that plant’s genes wide.

Lots of fruits had bigger seeds before we selectively bred the seeds out and shifted to cloning. Bananas were small and full of lumpy seeds before we fixed them. And then we have the occasional fruit that, even today, has a really big seed. We’re mean fruits like mangoes, or avocados. Years of artificial selection enlarged the edible part of the avocado, but we’re still stuck with that huge pit in the middle.

What’s the point of a seed that large? How could a fruit ever evolve seeds that size? There’s no way we can eat that seed whole to poop it elsewhere for the avocado plant, and we’re a lot bigger than most animals that disperse seeds (birds, rodents).

True, we aren’t big enough to swallow an avocado seed. But animals that big used to roam the Earth. We’re talking megafauna—animals like the mammoth, the 20-foot ground sloth, or the giant 2-ton glyptodont armadillo.

Many plants were spread exclusively by megafauna. That means they would have gone extinct the same time megafauna did, had humans not cultivated them. In addition to avocados, these plants include pumpkins and gourds. Also: the Osage-orange, a tree that bears a big yucky fruit that no animal touches, but which megafauna used to eat. After the 400-pound beavers died out, we cultivated and kept the Osage-orange alive, not for its unpalatable fruit but for its fast-growing wood.

When we humans die out, all these crops will vanish. If we care about them surviving after we are gone, we have only one responsible course of action ahead of us: We must bring extinct megafauna back to life, and set them loose as farmers. We must unleash the mammoth, the dire wolf, and—yes—even the Megalania, a 4,000-pound venomous lizard. It’s just like they told us in Jurassic Park. Mammoths make avocados. God kills mammoths. Millennials eat avocados. Avocados bankrupt millennials. Zoomers resurrect mammoths.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.

Top image: Ivar Leidus, Thomas Quine