Leopold and Loeb: The Not So 'Perfect' Murder

Murderers kill for all kinds of reasons -- money, the culmination of a decades-long revenge scheme, good old-fashioned sadism -- but perhaps the most annoying ones are those who do it to prove they’re so much smarter than police. Plenty of people have at least thought about it, but probably the most famous incident was the murder of Bobby Franks by Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, two snotty-ass teenagers who definitely weren’t as smart as they thought they were.

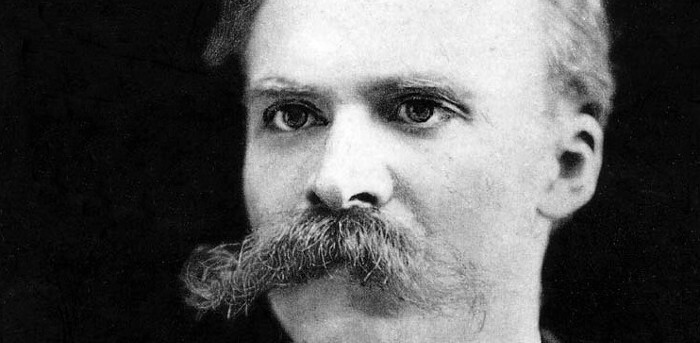

Nathan Leopold

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-00652/CC-BY-SA 3.0/Wikimedia Commons)

Nathan Leopold was your classic “gifted kid” with a reported IQ of 200 who, by 1924, had been admitted to the University of Chicago law school at only 19 years old. He was also “annoyingly egotistical,” claiming to speak 15 languages (which everyone seems to agree was an obvious lie), preferring the company of birds to other inferior people (he had already become a published ornithologist), and believing he embodied Nietzsche’s “ubermensch.” Basically, he was a huge douchebag.

Richard Loeb

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-00652/CC-BY-SA 3.0/Wikimedia Commons)

“Dickie” Loeb had also managed to complete a bachelor’s degree by the time he was 18, but he didn’t give nearly as much of a shit about school. He was more concerned with drinking, gambling, reading detective fiction (because he was still kind of a nerd), and committing petty crime for fun. He had everything Leopold lacked in the “good looks and charm” department and relished using them to manipulate others, thinking of himself as a “master criminal.” In other words, he was also a huge douchebag.

Boys Meets Boy

Leopold and Loeb met in 1920, but Loeb soon transferred to the University of Michigan, so they didn’t truly become friends until he returned to Chicago three years later. “Friends” is a bit of a misnomer: It’s generally agreed that they had a sexual relationship, though Leopold was more in his feelings about the whole thing. In fact, Loeb used Leopold’s obsession with him to convince Leopold to accompany him on his criminal endeavors in exchange for a good Dickie-ing.

The “Perfect” Murder

While Loeb went around vandalizing and burgling, Leopold bored him with lectures on Nietzsche, specifically the idea that the rules of society didn’t apply to superior beings, which he considered himself to be, ironically revealing that he was terrible at reading. Loeb wasn’t terribly interested in philosophy, but he did like the idea of fucking around without finding out, so they decided to commit the “perfect murder” essentially to prove how smart they were.

The Murder of Bobby Franks

They settled on Loeb’s cousin, 14-year-old Bobby Franks, who the pair persuaded into their rented car as they drove down the street near his house. In the car, Loeb bludgeoned Franks to death, then the two dumped his body in a culvert in Indiana, covered it in acid to obscure his identity, dropped their typewriter into a lake, sent a ransom note to Franks’s parents to throw them off their scent, and carefully cleaned the car before returning it and going on with their lives. They were certain they’d gotten away with murder.

The Investigation

(Chicago Daily News/Chicago Historical Society/Wikimedia Commons)

They were caught within a week. By the next day, Franks’s body had been discovered and identified, and police found a pair of eyeglasses near the body and the typewriter in the lake. The eyeglasses turned out to be a unique pair that had only been sold to three people, one of whom was Leopold. When the other owners readily produced their glasses, Leopold explained that they must have fallen out of his pocket when he dumped the b— went birdwatching. The typewriter had a few defective keys, so police dug up other documents Leopold had typed on it, and sure enough, they also had correspondingly wonky letters. It didn’t help that Leopold and Loeb had both mouthed off to the press about the murder in ways that made them look super guilty.

Their Confessions

There was pretty much no denying the crime for Leopold, who nevertheless immediately ratted out his boyfriend. Loeb likewise accused Leopold of actually committing the murder, but both described how they’d done it with the self-satisfaction and counterproductive detail of a Bond villain. So much for getting away with it.

Let’s Take a Politics Break

At this point, it should be noted that Chicago in the 1920s was, well, Chicago in the 1920s. You’ve seen the musical, so you know that it was a distinctly sensationalistic and murdery place to be during the Jazz Age, on which everyone blamed the sensation and murder. Freudian psychoanalysis was all the rage, as was Jewish in-fighting, evidenced by one “Jewish spokesman’s” claims that the murder was the result of “rich Jews who don’t know what to do with their money and who let their children grow up without any feeling of Jewish responsibilities.” So that’s fun.

The Trial

The popularity of psychoanalysis is relevant because the lawyer hired by Leopold and Loeb’s parents, the famous Clarence Darrow, had one job: keep them boys off death row. They’d confessed, so there was no possibility of acquittal and the “trial” was really more of a month-long sentencing hearing, where Darrow (a staunch opponent of capital punishment) called expert witness after expert witness to convince the judge that Leopold and Loeb couldn’t be held responsible for their crimes due to traumatic experiences in their childhoods and concluded with a now-famous twelve-hour speech.

The Verdict

Darrow’s strategy both worked and didn’t. Leopold and Loeb were each sentenced to life in prison plus 99 years, but only because, the judge said, they were so young, so Darrow could have saved his breath.

Life in Prison

(Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-10970/CC-BY-SA 3.0/Wikimedia Commons)

Surprisingly, going to prison actually seemed to chasten Leopold and Loeb. Despite turning on each other, they remained close, rejected media attention, and ran a school for their fellow prisoners, although hopefully they didn’t teach philosophy.

Loeb’s Death

Twelve years into his sentence, Richard Loeb died after he was cut and stabbed more than 50 times in the prison showers. His assailant claimed he acted in self-defense after rejecting Loeb’s sexual advances, but Loeb’s throat was cut from behind, so the “self-defense” angle is definitely dicey. It’s just as likely that Loeb died for turning down his attacker.

Leopold Solved … Malaria?

Free from Loeb’s influence, Nathan Leopold seemed to improve even more, taking over the school, reorganizing the prison library, and even offering himself up as a guinea pig for experiments in malaria treatments. Some believed these good deeds were cynical bids for parole, but Jesus, he kind of earned it.

Leopold’s Release

Leopold did get paroled in 1958 and went on to live a relatively quiet life in Puerto Rico before dying a relatively old man of a relatively normal heart attack. He wrote a memoir in prison, but he shunned any attempt to “trade on the notoriety” of his crimes, wishing only to live as a “humble little person.”

The Continued Relevance of Leopold and Loeb

(Dimension Films)

Leopold and Loeb’s story was dramatized within a decade by the 1929 play Rope, which became a Hitchcock movie in 1948, and as recently as 2002 in the Sandra Bullock movie Murder By Numbers, in which a thinly veiled version of Dickie Loeb is played way too handsomely by none other than Ryan Gosling. Possibly the most interesting homage, however, is the Scream franchise, which was kicked off by a pair of murderous teenage boys who were obviously probably also kissing.

Top image: Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-12794/CC-BY-SA 3.0/Wikimedia Commons