4 Reasons Music Biopics Are A Nightmare to Make

For those folks who ever listened to a popular song, enjoyed it, and immediately thought, "I'd like to spend two and a half hours watching someone dressed up as a performer wrestle with a drug problem and/or loveless marriage," there are, fortunately, music biopics to scratch this itch. The latest example is Baz Luhrman's flashy chronicle of the life of legendary singer/giant dirtbag Elvis Presley. But more often than not, these cliché-ridden dramas are tricky to produce for reasons such as …

Music Rights Are Sometimes Impossible To Secure

A big reason why people go see music biopics is to restaged performances of iconic songs – hence why Walk the Line climaxes with Johnny Cash playing his legendary Folsom Prison gig and not, say, the time he did a series of bank commercials in Canada. But filmmakers aren't always able to lock down the rights to an artists' original music, which leads to some pretty awkward workarounds. A lot of projects about iconic musical acts just include their cover songs, like Stoned, which was about late Rolling Stones drummer Brian Jones, and Backbeat, the movie about the early days when the Beatles mainlined speed and played more licensable songs.

More recently, there have been some pretty conspicuous examples of this, like the Jimi Hendrix movie Jimi: All Is By My Side.

And the recent David Bowie movie Stardust –

Since the Bowie estate didn’t allow for any of his songs to be used, he plays covers of Velvet Underground songs – but since they didn’t have the rights to those either, faux Bowie plays legally-dissimilar knock-offs, which is just weird.

Stories Are Almost Always Sanitized For Mass Audiences

Biopics, in general, are more full of crap than a broken Arby's restroom, and music biopics, not surprisingly, regularly bend the truth. Specifically, and frustratingly, they often weed out the more interesting, potentially controversial aspects of an artist's life in order to broaden its mass-market appeal as much as possible.

Most problematically, for Bohemian Rhapsody, much of Freddie Mercury's sexuality was sidelined and ultimately oversimplified. Because, more often than not, studios try to turn these musicians into sellable products at the expense of their inner lives. As a result, controversial subjects like Jerry Lee Lewis are turned into wacky cartoon characters, as with Great Balls of Fire, which Roger Ebert noted at the time "gives us a Jerry Lee Lewis who has been sanitized, popularized and lobotomized."

And giving their subjects a happy ending often negates major issues, like how the love story and drug addiction narrative in Ray wraps up neatly, despite the fact that Ray Charles and his wife later divorced, and while he kicked heroin, he remained an alcoholic – which ultimately killed him. And Walk the Line somehow neglected to mention the time Johnny Cash burned down a forest and killed "49 condors."

Of course, making certain edits may be the price you pay for accessing the artist's original music – which is why a lot of people are definitely not looking forward to the upcoming, estate-approved Michael Jackson movie.

Dubbing Actors – You're Damned If You Do, And Damned If You Don't

Filmmakers casting a music biopic have two choices; find someone who can sing just like the original performer, or go the Milli Vanilli route. Both have their advantages and some significant drawbacks; even if you can find someone who can act and sing in the style of the subject, it's doubtful that they would ever truly capture the magical quality that made them an icon in the first place. Joaquin Phoenix won numerous accolades for portraying Johnny Cash but arguably never comes close to the soulful Southern baritone of Cash – making his rise to fame within the world of the movie somewhat baffling.

Similarly, Renee Zellweger's singing in Judy never comes close to approximating the real Judy Garland's, Taron Egerton was never convincingly Elton John-like when singing in Rocketman, and even one of the best examples of a music biopic in recent history, Love & Mercy, struggles when Paul Dano, who's clearly a capable singer, can't match the effortless range of Pet Sounds-era Brian Wilson.

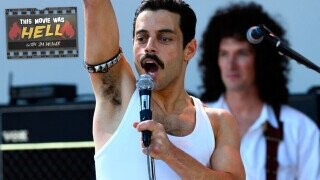

Then there's the option to dub the actor, like how, despite being a legit singer, Jamie Foxx lip-synced his role in Ray using Ray Charles' original tracks. And weirdest of all, Bohemian Rhapsody, presumably in an effort to side-step any perceived phoniness, Frankensteined Rami Malek's voice with that of another performer, Marc Martel, who is known for his stellar Freddie Mercury impression.

Of course, with this option, you run the risk of turning your movie into a feature-length Jimmy Fallon bit.

Music Biopics Are Lightning Rods For Lawsuits

The combination of intellectual property and purportedly true stories makes music biopics a veritable Mardi Gras parade of lawsuits. This isn't a recent phenomenon either; even back in the 1950s, Universal's The Glenn Miller Story sparked multiple suits, including from Miller's widow, who said that she hadn't authorized a soundtrack album release. And in 1978, the studio behind The Buddy Holly Story was sued by multiple parties, including the widow of music legend Sam Cooke, who claimed she had "not been compensated for the use of her late husband's image" and also that "the singer was portrayed falsely in the film."

More recently, Johnny Rotten was sued by bandmates in order to use the Sex Pistols' music in a recent series, TLC's former manager sued over a VH1 TV movie, and the yet-to-be-made Janis Joplin biopic has been a real legal quagmire. Perhaps the weirdest example, though, is the 2016 Tupac biopic All Eyez on Me –

– which was sued for copyright infringement by former Vibe journalist Kevin Powell because some of his old articles about Tupac contained a "made-up character," and that bogus personality ended up in the movie.

You (yes, you) should follow JM on Twitter!

Top Image: 20th Century Studios