In 1844, Americans Sold All Of Their Stuff Because Jesus Was Coming Back

Welcome to Oofageddon! a.k.a. Cracked's round-up of doomsday prophecies that screwed the pooch. You can find Part 1 of our series here.

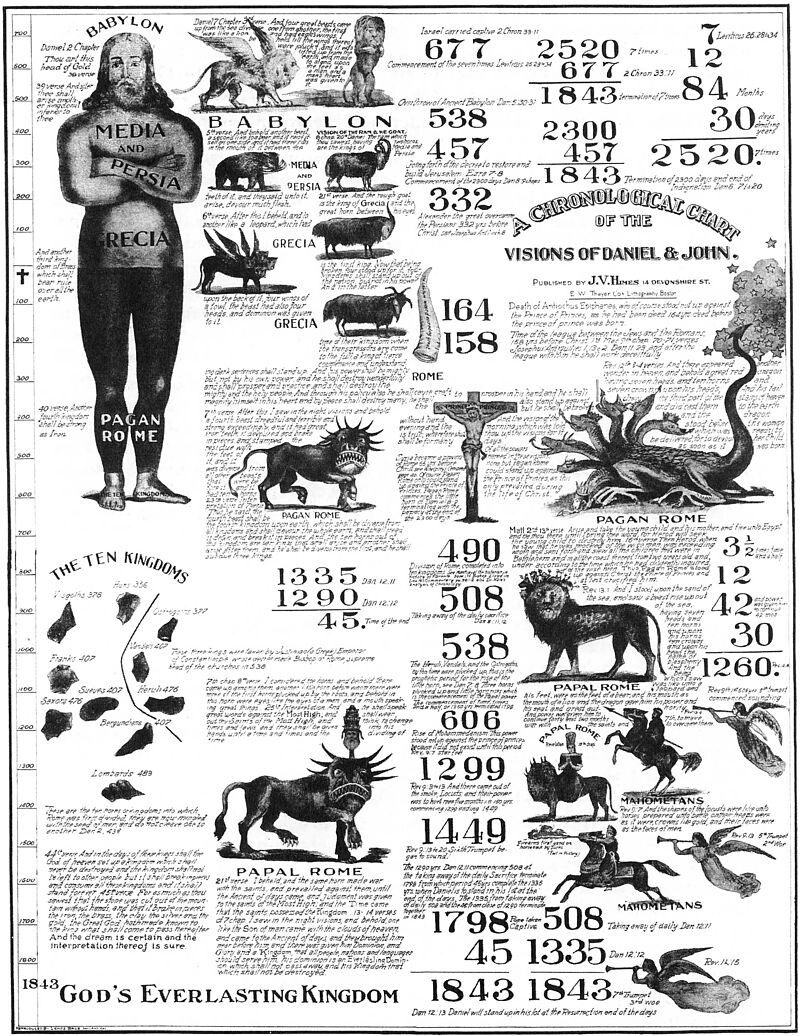

In 1818, William Miller had an idea. Born a Baptist, the farmer became a Deist but began re-exploring his family’s faith after his miraculous survival in the War of 1812 got him asking the Big Questions. As he studied the Bible with fresh eyes, he became especially interested in Daniel 8:14, “Unto two thousand and three hundred days; then shall the sanctuary be cleansed.” Assuming Earth was the sanctuary and Christ was returning to cleanse it, and working from some arbitrary assumptions about how and when to begin counting, Miller determined that Big J would return around 1844.

Now, Christ’s return has been predicted so many times that it became the theological equivalent of Arrested Development’s “But it might work for us” gag well before 1000 AD. But Miller’s prediction was unique in its appeal, its consequences, and the fact that it hurt and embarrassed a whole lot of people.

Don't Miss

So, what did Miller do after he’d reached this incredible conclusion? First he carefully checked and rechecked his calculations until 1823, when he felt confident enough to share his belief with a few friends and fellow churchgoers. Disappointed that “the great majority passed it by as an idle tale,” in 1832 he did what any budding crank would and fired off a bunch of articles to a local newspaper, which dutifully began printing them because apparently anyone could get in an old-timey paper.

This got results. Inundated with questions, comments, and requests to travel and preach, an overwhelmed Miller wrote a little book on his beliefs and sent a copy to anyone who got in touch. He had struck a nerve, because America’s never been short on people who are eager to see Christ’s return, but this whole affair would have remained an unusual mail club if not for Joshua Vaughan Himes.

Himes was a Bostonian preacher and publisher who thought Miller had some interesting ideas, and after some time promoting Miller he eventually became a full-fledged believer. In 1840 he began publishing Sign of the Times, a newspaper promoting what critics now called “Millerite” ideas. More circulars followed. A driven and well-connected man, Himes arranged speaking tours, printed collections of Miller’s writings and lectures to distribute far and wide, and generally became the mid-19th century equivalent of a relentless hype man.

The media blitz was calculated. There was a publication aimed at women, one meant to convince clergy that Miller was theologically sound, and regional papers everywhere from Montreal to Liverpool. By 1844 Himes claimed to have printed five million copies of various Millerite publications, and over a million Americans had heard Miller speak. Himes had left his own pulpit to dedicate himself full-time to Miller, prompting one of his old abolitionist pals to declare him “the victim of an absurd theory.”

However absurd it was, the theory was gaining traction. While most Millerites were concentrated in America, the belief had reached as far afield as Norway and Chile. How many believers Miller actually had is debated, but it was probably no more than 100,000 serious followers, plus some curious hangers-on. Those 100,000, however, were starting to need results.

James Andrews1/Shutterstock

The 1840s were a good time to start a religion. America was entering a Third Great Awakening that would create beliefs ranging from Christian Science to Theosophy, and Millerism was a preview. Miller wasn’t some charlatan looking to make a buck or form a harem; he was genuinely concerned for the fate of human souls. He also never claimed to have all the answers, suggesting windows for JC’s big return but admitting he could be wrong.

But “Jesus is coming back sometime in the spring, unless I goofed up my math” doesn’t make for a good apocalypse, and Miller’s followers began demanding specific answers. To placate them, Miller first suggested that Jesus would return sometime between March 21, 1843 and March 21, 1844. When that passed without incident Miller preached hope and his movement, after study and debate, soon settled on a new deadline of April 18. When they struck out again there was still optimism, but there was also a sense that Millerism wouldn’t survive a third miss.

As is often the case in religious movements, the rank and file became more extreme than their leadership. And during a Millerite camp meeting, a fellow named Samuel S. Snow presented a theory. Snow, once a skeptic who contributed to an anti-religious Boston newspaper, converted to Christianity after coming across a book of Miller’s lectures. Snow had dug deep into the fringes of Biblical scholarship, and he emerged with a conclusion: Christ was returning on October 22, 1844. No excuses.

This was news to Miller and Himes, but Snow’s prediction proved so popular among their followers that they were forced to accept it. Miller’s vagueness had attracted supporters, but ultimately they needed something specific. When the big day came, believers gathered in homes and churches, on mountains and meadows. They waited around, growing more and more anxious as darkness fell. And when day broke on October 23rd, they went home.

This failure had consequences. For starters, some Millerites had given away all their possessions or refrained from planting crops. One reported lying in bed for two days, “sick with disappointment.” Miller himself was taunted in the street, even by children, which is a little funny. Less amusing is the fact that several Millerite congregations were beaten and shot at. Miller had long been a target of mockery by mainstream papers and pulpits, which made believers and foes alike double down until Millerites were being beaten for their faith.

The anticlimax was dubbed the Great Disappointment, and it became a quintessential example of what happens when believers are, well, disappointed. Most Millerites lost their faith or slunk back to the orthodox beliefs of their old churches. Others joined the Shakers, who had been in the “Christ’s return is right around the corner” game for almost a century. And still others stuck with Millerism.

Hey, the fourth time’s the charm, right? A few different theories on the letdown emerged, including that Christ had returned in spirit if not in body, and that something important had happened in heaven but not on Earth. The latter became the bedrock of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, which was founded by some of Miller’s acolytes and, as of 2015, boasted 18.7 million members worldwide. Both one of the fastest growing Christian denominations, and one of the most racially diverse, famous members of their flock include Sojourner Truth, Ben Carson, Little Richard, Magic Johnson, and W.K. Kellogg (who, while a prude, didn’t actually invent Corn Flakes to keep folks from cranking it).

There are other Adventist churches out there, although Seventh-day is by far the largest. They still believe Christ will return soon-ish after a “time of trouble,” but while they recommend being spiritually prepared they also note that trying to pin down God on a calendar is folly. Today they’re mostly just Protestants who worship on Saturday and are really into nutrition. They still publish Sign of the Times.

Millerism gave us a more winding road to the Jehovah’s Witnesses too. Oh, and the Baháʼí Faith thinks that Miller was right all along. See, a fellow named Báb (not the name his mama gave him) began preaching in Persia in October 1844 and, despite founding a different religion, is considered one of the forerunners of Baháʼí. Miller got the prophecy of a saviour’s arrival right, they say, just the continent wrong.

Miller himself enjoyed a quiet retirement, and he still believed that Christ’s return was imminent when he died in 1849. Himes joined the post-Disappointment debate and eventually became a key member of the Advent Christian Church, which lost the popularity battle to the Seventh-day Adventists, but is still chugging along with about 25,000 members today. Snow eventually declared himself a major prophet, began styling himself “Christ’s Prime Minister,” and demanded that all earthly rulers surrender their power to him on behalf of Jesus lest “catastrophic consequences” befall them. When pestilence didn’t sweep the land he faded into obscurity.

The Great Disappointment is now a textbook example of cognitive dissonance, but it’s also an example of how modern media can spread an apocalyptic movement that evolves beyond the one man it first focused on. If all your friends think your new ideas are weird, reach out into the big wide world until you find people who agree with everything you say. And hey, at least the Millerites didn’t accuse everyone who disagreed with them of being a pedophile.

Mark is on Twitter and has a brand new collection of short stories.

Top image: Wikimedia Commons, Phillip Steury Photography

You can check out further installments of Oofageddon! below:

The Woman Who Was Pregnant with the Messiah (at 64)

In 1910, Americans Thought Halley's Comet Was A Doomsday Event

In The '60s, The Truly Devoted Believed Aliens Would Save Us From Nukes

In The 1970s, A Bestseller Claimed The Planets Would Align And Destroy Everything