5 Disasters Deleted From Your History Books

Social media is terrible in most ways, but it means you live in the golden age of disaster footage. Every day, if you know where to look, you can find new videos of crashes, collapses, and explosions. Each of these clips—even a few decades ago—would be so unique, they'd melt the brains of a whole generation.

Back then, cameras were almost never around to catch disasters in the moment. You'll therefore just have to picture in your mind the sight of how ...

Oil Wells Looked So Cool, A Crowd Gathered To Watch One And Died

The early days of oil were a wild time. You could dig even a tiny bit into the soil and discover a reservoir of oil just waiting to shoot up to the surface. Today, those massive deposits of oil in the Gulf of Mexico? We had to drill miles below the surface to reach those. The first commercial oil well in America, however, Pennsylvania's Drake Well, went down only 69 feet before hitting a nice little layer of oil floating on a larger chunk of water.

In 1861, one Henry Rouse struck black gold digging 300 feet in Venango County, Pennsylvania, part of a stretch along the Allegheny River called Oil Creek thanks to all the shallow oil people kept finding. Rouse built a well at his site, sending oil gushing to the surface and spurting like a fountain. On April 17, people from the town came to watch the marvelous creation. The oil splashed all over everyone's faces, but they were into that, because people were pretty kinky back then.

Then something set the oil alight. Some say it was Rouse himself lighting up a victory cigar, while other accounts say Rouse had banned all smoking but a bit of machinery still let off a spark. The sound of the boom traveled miles, and the fire shot 300 feet in the air—that's the same height as the well's depth, since science is poetic like that. Dozens of people who'd been watching the gusher caught fire of course, and 19 of them died.

Rouse too caught fire, though he wasn't the closest to the well. Instinctively, he first threw out a valuable book from his jacket and a wad of money, as saving them from destruction seemed the highest priority. Then he remembered his face was also on fire, so he ran to patch of mud and buried his head in it to put out those particular flames. The fire had severely burned him, and workers now approached him to feed him water through a spoon, while he dictated his will—again, this guy put business first. This will contains a few bits of confusion from a dying man ("I have a little namesake, Harry Rouse in East Granby Connecticut ... I cannot think of his name ... his name is Harry Rouse Viets"), and after various bequests, including leaving sums to two men who'd helped him almost escape the fire, he left his estate to the city for public works.

A pastor came by to offer last rites and take his confession. Rouse refused, saying, "My account is already made up. If I am a debtor, it would be cowardly to ask for credits now." And he died. We'd say he died at peace, based on those last words. Except for the fact that he was still lying at the site of a growing fire that would spread to four other oil wells and would eventually only be put out by dumping a bunch of animal poop on top of it.

An Early Passenger Plane Bombing Was One Guy Filling His Mom's Luggage With Dynamite

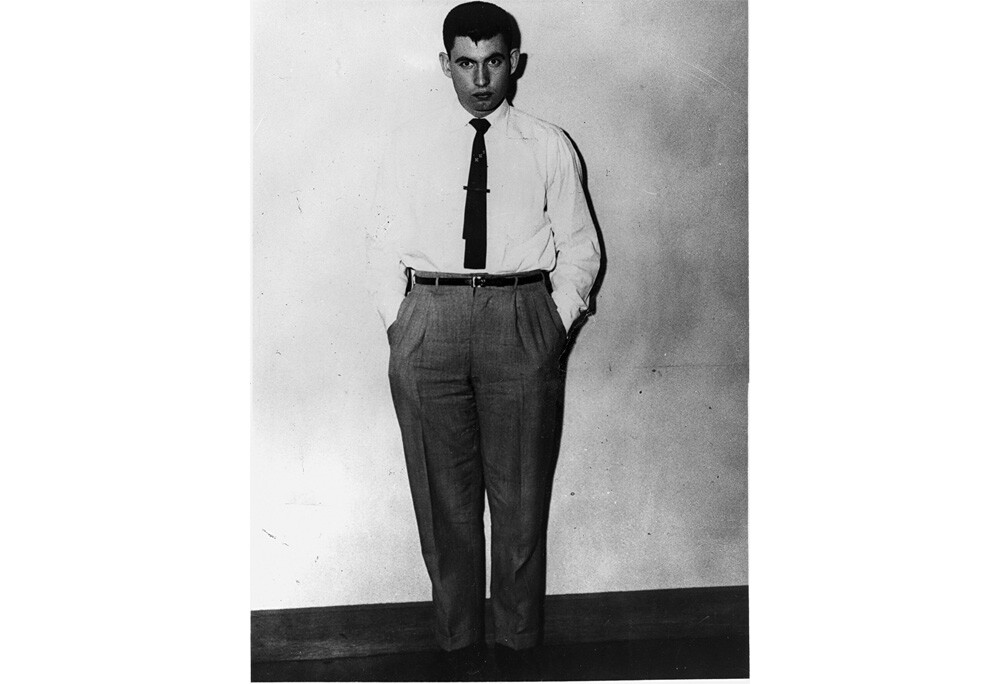

Jack Gilbert Graham grew up in an orphanage. He was not, however, an orphan. His father died in 1937, and his mother Daisie then palmed him off on her own mother and then on a “boys' home,” which was something you could do back during the Great Depression. She remarried, became a widow again, and now grew rich running restaurants, and yet she did not get back in touch with her son. Jack did manage to live with other relatives, including his half-sister in Alaska, who'd later say he enjoyed blowing things up. For example, when he was working in construction and a bolt was too tight to loosen, he'd just blow off the bolt with dynamite.

At 19, Jack got a job as a clerk, embezzled $4,200, and spent the money on a convertible. Police caught him hauling whiskey over state lines. They put him in jail for a while for the earlier theft, then released him on the condition that he keep making payments to return the money. He now hunted his mother down and asked for a job at her restaurant. She gave it to him, but people said the two argued a lot. Then someone blew up the restaurant. We can’t even begin to speculate on who was responsible for that, but Jack was the beneficiary on the insurance policy.

Insurance is an easy way to make money, it turns out. Life insurance policies pay especially well. And do you know the easiest way to buy life insurance in 1955? It was at the airport, where you could order it right in the terminal—insurance offered passengers peace of mind and encouraged them to buy tickets, rather than, as you might expect, doing the exact opposite. So, two months after the restaurant explosion, Jack took out a life insurance policy on his mother at the airport. She boarded United Airlines Flight 629 from Denver to Anchorage. The plane exploded in midair, killing all 44 aboard.

It blew up because Jack had inserted into his mother's luggage 25 sticks of dynamite and a timer that set off some blasting caps. Picture the most cartoony bomb you can imagine—that was in her suitcase, and this was decades before airport security became a real thing. Flight 629 was the first passenger plane brought down by a bomb, and yet this was not a case of terrorism. It was murder. Terrorism is when you have political goals; killing someone for personal reasons is murder, even when it involves mass death and aircraft.

Prosecutors did aim to charge Jack with blowing up an airplane, but they discovered no existing law covered that. In fact, to ensure a conviction, they then didn't even bother charging him with multiple counts of murder. They charged him just with murdering his mother, an accusation they easily proved. Barely a year after the crash, Colorado put Jack to death in the gas chamber.

Six months later, President Eisenhower signed a new bill into law. From this point on, it was officially illegal to bomb a commercial airline, so all of you who were otherwise thinking of bombing planes, revise your plans accordingly.

Scores Died Crowding A Bridge To Watch Geese Pull A Clown In A Bucket

In the spring of 1845, the English seaside town of Yarmouth saw the following advertisement and cheered:

via Wiki Commons

“Stay away!” you now yell at the people of Yarmouth, across time. "Clearly, that clown means to murder your children!" The people of Yarmouth would not heed your warning. This was a stunt by Cooke's Royal Circus, which had been performing since 1780 (and would continue performing right into the early 20th century). They were a reputable organization, and if they were showing off one act for free to the public, that would surely be great fun for all.

You might point out that this clown, like all clowns, had to be a fraud. Geese cannot pull watercraft. They are neither strong enough nor obedient enough. If a clown gets in a washtub tied to geese, he can only go downstream, not upstream like the ad says. "Well, that's what will make this trick so fascinating," the people of Yarmouth would argue. The way this trick actually worked, a distant rowboat would tow the tub, the water would hide the towing line, and it would look like the geese were pulling the tub (so long as they faced the correct direction).

The second of May arrived. Some 400 people stood on the Yarmouth suspension bridge over the River Bure awaiting the clown's arrival. They all pressed themselves to one side of the bridge, and this was more than the improperly welded structure could bear. The chain holding up the bridge failed, and the bridge tipped into the river.

This river was only 7 feet deep. Thousands of other spectators stood on the river bank, and possibly, they would have been able to save everyone from drowning. In fact, one woman named Gillings jumped into the water, seized her kid's clothing with her teeth, and then swam to shore. But the victims faced not just the danger of drowning but the weight of the bridge falling on them after dropping them into the water. The bridge collapse ended up killing 79 people—including, yes, dozens of children.

The inquiry following the disaster centered on the bridge specifications, the quality of the metal, and the craftsmanship. No one directed their attention toward Nelson the Clown, who'd vanished right after luring the people of Yarmouth to their doom. In fact, no further record exists of the clown. Other than faint ghostly laughter still heard along the River Bure, occasionally punctuated by gleeful honks.

A '70s Dam Accident Killed Tens Or Even Hundreds Of Thousands, But China Covered It Up

China wanted to build a whole lot of dams in the 1950s. They didn't actually know a dam thing about building, so they sought help from the one country that never made any mistakes during construction: the USSR. With the blind leading the blind, they built the Banqiao Dam over the Ru River. They informally dubbed it the "iron dam" because they considered it unbreakable. "Even God could not break this dam!" they would have said, if belief in God were not forbidden by law.

When you build dam systems, you construct them to both retain water and mitigate floods. The Banqiao Dam, and the surrounding dams in the area, put a lot of effort into the former, since Mao's farming plan treasured water, but not so much the latter. This worked well enough for a quarter century. Then came 1975 and a massive storm known as Typhoon Nina. Almost 5 feet of rain fell, over the course of three days.

The Banqiao Dam broke, and it broke 61 other dams by dumping its water toward them. This killed as many people as 100 Katrinas. We don't even know the death toll for sure, but Human Rights Watch puts it at 230,000, a combination of people who first died when the water plowed through a million homes and those who died in the famine that followed. The Chinese government did airdrop supplies on the area afterward, but they dropped about half of that right into the water, so it sank before it could reach anyone.

If you were around in 1975, you didn't hear anything about the Banqiao Dam on the evening news. China was a closed nation, it didn't release any info on the disaster to the outside world, and the communist government forbade anyone in the know from reporting on it. All the Chinese press said at the time was that, yes, flooding had occurred, but the army had heroically stepped in and handled matters.

via Wiki Commons

It took 20 years for a Chinese news agency to write up what had happened in a book, and it was ten years more till China officially declassified info and held a seminar revealing details. Even then, China claimed a death toll just one-tenth of the upper estimates. "From now on, we will be open and honest about all such matters," declared the CCP, lying.

The Sewers Of Louisville Exploded Thanks To Gas From Beans

We could have built up to that last story and ended there, since we don't have any disasters under our hats that killed more than a quarter million people. Instead, let's ease you back into your everyday life by talking about a lighter incident in Louisville, Kentucky, which killed no one at all. It's pretty amazing that it killed no one, though, since 13 miles of roads exploded, and everyone who saw it thought some enemy nation was dropping missiles on the city.

In was February 13, 1981. Early in the morning, two women were driving to the hospital to start their workday, and as they drove under a railroad bridge, the car let off a spark. This ignited gas in the sewer below them, and the road blew up, throwing the car in the air then dropping it on its side. The fire traveled along the sewer line, blasting through the pavement and overturning more cars. Chunks of concrete rose from the ground and smashed through the walls of stores.

Weighty manholes shot into the air. One crashed into a home and narrowly missed flattening a 10-year-old boy. Another, on its way back down from the heavens, broke through an apartment's ceiling, broke through the floor next, and damaged the apartment one story below too. The National Guard evacuated the city of thousands of people when the blasts were done blasting. Not a single person had been standing on the streets when they exploded, because that had happened at 5:15 AM—four hours later, and that would have made for a very different story.

The culprit in all of this? Someone had been discharging toxic solvents and hexane gas into the sewers. This someone was the company Ralston Purina, whom you might know for Purina Puppy Chow but who at the time were in the business of processing something far less tasty: soybeans. The company faced a $62,500 fine for the $25 million of damage, and they ended up paying a few million more. Then, thanks to all the dirty looks people kept giving them, they abandoned their Louisville soybean plant. The University of Louisville used the place as a billboard for years, sticking their name on a row of silos. People said this looked trashy, even for Louisville, and the university finally tore the silos down.

We hope you had a good time chuckling at the time underground farts blew up Louisville, and we trust you will in no way now feel paranoid every time you step on a manhole. Sure, two manholes exploded in Boston just last week, shaking the ground and sending fire into the sky, but your nether regions are perfectly safe. Just trust us.

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.

Top image: FBI