Meet 'Varney,' The Vampire Who Popped Up 50 Years Before 'Dracula'

In the 1840s, most people thought of vampires as something nasty that happened only in Eastern Europe, like A Serbian Film and bad Eurovision contestants. From the 1670s to the 1770s, western Europe and Great Britain were treated to dozens of newspaper articles about vampire “epidemics” taking place from East Prussia to Russia and from the Istrian peninsula to Romania. There had been a decade-long literary craze for vampires in the 1820s inspired by John Polidori’s 1819 short story “The Vampyre,” the first vampire short story. But by the mid-1840s, the vampire craze had ended, and most uses of “vampyre” or “vampire” were scientific, about natural bloodsuckers like bats, leeches, and executive producers.

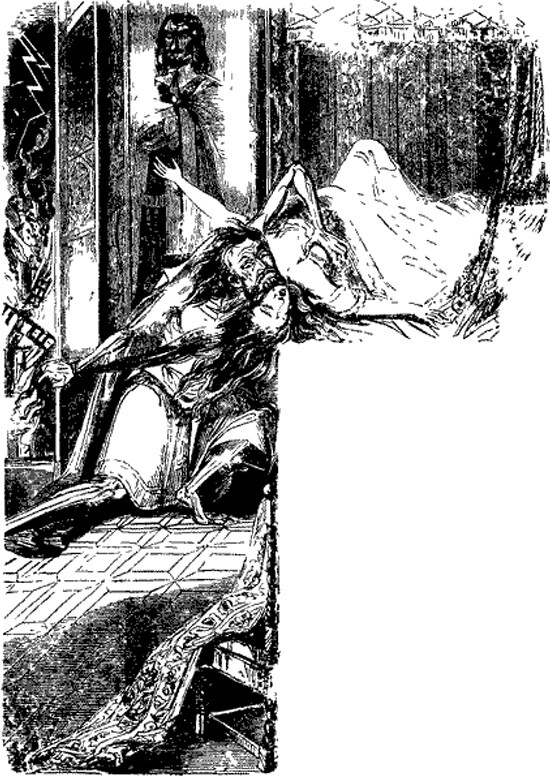

One penny blood (serialized novels -- the more blood-soaked, the better) changed everything and gave us the hip, hawt undead bloodsuckers we know and love today. That penny blood was Varney the Vampire (1845-1847), and without it and its titular protagonist, the modern vampire would look a lot different.

The Men Responsible for Varney

Varney the Vampire is the second-longest penny blood ever; it was published in 109 issues comprising 232 chapters and is a little over 666,000 words long—an appropriately Satanic number for the world’s longest vampire novel.

Varney was published by Edward Lloyd, a major publisher of penny bloods, in the mid-1840s. His “thriller factory” encouraged penny blood writers to churn out text at a breakneck speed with no regard for continuity, concentrating on a fast pace and galloping suspense rather than coherence or nuanced character development. (If this reminds you of superhero comic book publishers, it should). Like other penny blood publishers, Lloyd discouraged his writers from setting their names to their work on the grounds that it would be “distracting” to readers.

So we don’t know for certain who wrote Varney. Scholars have theorized that most of Varney was written by James Malcolm Rymer (1814-1884), with the rest being written by Thomas Prest (1810-1859) and (possibly) two other unknown authors. Prest was a successful author of around one hundred penny bloods, but was also a huge plagiarist who died in obscurity of tuberculosis at age 49. (That’s what you get for copying other people’s work, kids: being buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave). Conversely, Rymer only ever published his own work, writing over 120 penny bloods, creating both Sweeny Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street and Varney the Vampire, and dying wealthy and comfortable at age 70. (Take that, Prest).

Varney’s “Plot”

Varney is about the (very) long quest of Sir Francis Varney to acquire blood to live on, in the form of a beautiful young virgin who he can marry and then suck dry. Lacking this wife due to Plot Reasons, he resorts to the women near him to feed on. He wants to “obtain the voluntary consent of one that is young, beautiful, and a virgin” (this diet is the Victorian predecessor to keto), but lacking that, he’ll settle for someone young, beautiful, and virginal who he’s not married to.

Varney is emo, haunted by guilt, full of self-criticism, and a drifter in a world that hates and fears vampires. Who better, then, to become the icon of the undead? Varney’s tall, gaunt, so pale as to have pure white skin, with “eyes like polished tin” and a head full of long black hair. Basically, he’s the Victorian beta version of The Cure’s Robert Smith as a young man. (One at a time, comrades! The line forms on the left!).

Varney begins with Varney attacking Flora Bannerworth, the adult daughter of the wealthy Bannerworth family, but he is interrupted before he drains her completely, and then her family guards her too closely for another attack, so Varney takes a new approach. He cozies up to Flora as a friend, eventually proposing marriage, which she declines in a kind and friendly way. The local mob starts chasing Varney before he can wear down Flora’s defenses and eventually kill him.

However, Varney is the type of vampire who recovers from death through exposure to direct moonlight, and whenever he is disinterred, which is what happens, he comes back to unlife. Varney reinvents himself as “Baron Stolmuyer Saltsburgh” in order to marry the virginal Helen Williams, but Admiral Bell, Flora Bannerworth’s uncle, interrupts the wedding and leads a mob in chasing Varney away. Varney escapes to London, where he repeats his wedding scheme, this time posing as a Colonel, but once again, Admiral Bell ruins Varney’s scheme and forces Varney to flee.

And so it goes: failures for Varney in Winchester, Bath, Naples, Venice, Florence, and again in London, always suffering through wedding interruptus thanks either to Admiral Bell or a friend of Admiral Bell. Back in Italy, a desperately lonely Varney succeeds in creating a vampiress out of a young woman, but she quickly gets staked by a blacksmith. Despairing, Varney travels to Mount Vesuvius and throws himself into its fires, finally succeeding in killing himself for good.

That Was A Lot

It certainly was—and Rymer et al. often didn’t help matters for readers. Varney the Vampire is an archetype of the penny blood format, which means that it often reads like the authors were paid by the word, which they were. The individual chapters are full of padding and redundant dialogue. Scenes tend to repeat themselves with only minor variations. The authors take a few storytelling detours whose only purpose is to make the authors more money. The story’s too long by a third, the comic characters aren’t, there’s too much coincidence, and Varney never thinks of even the simplest of tactics (like gags for his would-be victims to prevent them from screaming for help) to help himself get what he wants. Varney isn’t the worst penny blood ever written—that would be Thomas Prest’s The Maniac Father; or, The Victim of Seduction—but it has things in common with it.

And yet, and yet. Varney also has its virtues. Rymer’s style has aged only a little. The glacially paced lulls are offset by action scenes in which Rymer achieves a sustained pace and a feverish atmosphere. Although the dialogue often veers toward the turgid, there is also the occasional flash of humor. Varney is often a page-turner, and the modern reader will want to keep reading to its end. The reasons for this are not the love stories between Varney’s chosen victims and their true loves, who would be rejected from the Lawrence Welk Show for being too boring and white bread. It is Varney himself who grabs the reader’s attention. He’s compelling. He makes his first appearance in Varney as a monster, one of the few truly supernatural monsters in the Gothics, penny bloods, and penny dreadfuls, but he is soon introduced as Sir Francis Varney, and it is in that identity that the reader gets to know him.

Varney is given a surprising depth of characterization by the authors—surprising not just for penny bloods, whose authors usually lacked the ability to give their characters more than a fraction of a dimension of characterization, but also surprising for later, better-written 19th-century horror novels with similar monster characters. Varney is more fleshed-out, more emotionally recognizable, and more three-dimensional than Rymer’s Sweeney Todd, than the werewolf White Fell in Clemence Housman’s The Were-Wolf (1896), than J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s vampire Carmilla in “Carmilla” (1871-1872), more than the Creature in Shelley’s Frankenstein, and even more than Dracula. Varney is the most complex and emotionally identifiable monster in 19th-century fiction. I know; it surprised me, too.

Varney’s Firsts

Moreover, Varney is the home to a particularly notable moment as well as a number of firsts for vampire fiction.

Near the beginning of Varney, after Varney has attacked Flora Bannerworth, her brothers and her lover refuse to believe that a vampire attacked her because they don’t believe God would allow such creatures as vampires to exist, and “we disbelieve that which a belief in would be enough to drive us mad.” Contemporary readers of Varney had plenty of experience with horror, from short stories, the Gothic novels and serials, and art—the concept of the sublime had been a popular one in both fiction and art and literary theories during the late 18th and early 19th century. The sublime was what philosopher Edmund Burke wrote was “whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger.... Whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror.” (The Romantics would say that Adam Sandler is sublime, as are Toby Keith, Luxembourg, and I.P.A.s).

The “we disbelieve” line in Varney is an allusion to the sublime and the horrors of the Gothics, but it’s a very Protestant response and represents a kind of Protestant reaction to the sublime, the horrors of the Gothics, and to a very Victorian kind of cosmic horror.

When Rymer et al. wrote Varney, there was plenty of folkloric material about vampires but comparatively little literary material; John Polidori’s “The Vampyre” (1819) was the most famous vampire story at the time. (Polidori makes a brief appearance in Varney as “Count Pollidori”). So Rymer was forced to make up a lot of material about vampires. Varney is:

– the first vampire novel in the English language

– the first sympathetic vampire protagonist

– the first emo Goth vampire, the first vampire protagonist to be straight out of Romanticism, the first to be haunted by his crimes

– the first vampire story to emphasize the sexual aspect of the vampire’s feeding

– the first vampire story to emphasize the vampire’s Eastern European background

– the first vampire story to provide a pseudo-scientific rationale for the vampire’s powers (which also makes Varney an early work of science fiction)

– is the first vampire story to show a mob hunting for and then chasing a vampire

– the first vampire story to show a vampire using sharpened teeth/fangs to feed upon his prey

– the first vampire story to show a vampire with superhuman powers, including hypnosis and superstrength

Differences Between Varney and Modern Vampires

Unlike modern vampires, Varney can be revived after he “dies” by exposing him to a jolt of electricity or to moonlight. Varney’s overwrought guilt and self-directed recriminations are echoed in modern emo/tragic vampire protagonists, but his mercilessness when ravenous is not. (Rymer et al. were willing to let Varney be a true, ghastly monster at times; modern vampire authors rarely are with their protagonists). Varney becomes a vampire not through being bitten by another vampire, as most modern vampires are, but through the direct act of God when He is displeased with Varney’s actions. (Killing his son and betraying a Royalist to Cromwell earns Varney God’s curse; killing numerous young women does not. Varney is covertly subversive and proto-feminist). Unlike modern vampires, Varney only feeds on beautiful young women, although Varney is unclear whether this is Varney’s choice or something that is forced upon him.

Summary

Varney the Vampire isn’t the easiest of reads. Only obscurantists and those who are really and truly interested in vampires—like, really interested in vampires, to the point that it’s all they talk about—we know, Dave, you like vampires, move on, already—read it today.

But Varney, and Sir Francis Varney, are interesting what-ifs in the history of vampire literature. In our timeline, Le Fanu’s “Carmilla,” Stoker’s Dracula, and Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire all combined to create the modern vampire, who can range from a Victorian monster to a very modern creature of the night. But if Varney the Vampyre had not been superseded by Le Fanu and Stoker and Rice, the vampire might have remained something fraught with melodrama, guilt, and Gothic overtones—Iggy Pop in a somber, fitted mid-1840s tailcoat rather than Tom Cruise in a Revolutionary War outfit or Matt Berry in a vest and puffy sleeves.

I say we missed out.

Follow Jess Nevins on Twitter or his podcast, The Encyclopedist, for more half-crazed notions.

Thumbnail: Edward Lloyd