6 Ways Satan Influenced The Course Of American History

Cracked has never been a site that shies away from controversy. Whether it’s stupid controversies in film, stupid controversies in gaming, or stupid controversies in pop culture, our loyal readers can rest assured that–if a topic is equal parts controversial and stupid–we’re all over it.

I’m proud to continue that fine tradition by exploring a less stupid but certainly controversial topic: Satanism in America. Cracked emeritus Adam Tod Brown once speculated that talking positively about Satan could get the Cracked offices firebombed, fear of or allegiance to the Prince of Darkness motivates the everyday actions of millions of Americans. A 2016 Gallup poll found that 61% of those living in the U.S. believe that Satan is a literal being, proving that Americans are–to paraphrase Batman–a superstitious, cowardly lot.

Don't Miss

Over the next five days, we’ll explore America’s fascination with Satan to better understand how and why such a clearly fictional figure could inspire such strong emotional responses. Let’s start by unpacking the origins of Satan as a figure and how he found his way into American culture.

Where The Devil Did The Devil Come From?

Beelzebub first appeared in early Jewish mythology as a member of the court of Yahweh (that’s the Hebrew name of God for those keeping score at home). While his backstory as a fallen angel didn’t develop until later in Judaism, he was originally described in texts as an enforcer for God, sort of like the Storm Shadow to a divine Cobra Commander. In fact, the name “Satan” derives from a term meaning “one who obstructs.”

Gustave Dore, Hasbro

Like most ridiculous concepts, this figure was absorbed into Christianity. As early Christians were persecuted by the Romans and other foes, Satan was described as just another persecutor. The popular conception of the devil–a goatlike figure with cloven feet, horns, and a tail–first appeared in Europe during medieval times.

Although some European intellectuals like John Milton and William Blake would see admirable traits in Satan as the ultimate rebel and defier of authority, Christianity did what it does best and used him as an excuse to persecute anyone who stepped out of line with orthodoxy. “Witches” were accused of casting spells and communing with Satan, leading to the systematic murder of 50,000-100,000 individuals, an estimated 80%+ of whom were women.

So America clearly had a mature, reasonable model for reflecting on Satan when the concept made its way across the Atlantic.

Satan in Colonial America

With so many Old World traditions being shed when colonists arrived in the New World, why did settlers cling to the idea of Satan? The concept of an external evil is a huge boon to Americans because it draws attention away from their own misdeeds. We can easily shirk moral responsibility and blame if everything wrong that we do is caused by someone else. In America, the devil is basically anything that scares you or threatens your personal security or safety. As we’ll see, the Venn diagram of “Satan” and “The Other” sadly overlaps all-too-often.

Since this conception of the devil is so useful, it traveled to the Americas along with colonizers. Mass persecution likewise made its way to the New World, reaching its apex in the Salem Witch Trials of 1692 and 1693. The so-called “City upon a Hill” of the Puritans had many enemies in the form of iconoclasts who resisted New England’s rigidly structured theocratic order. In a “hold my beer” moment between Salem and Europe, all but one of the 25 people who died as a result of the trials were women.

While things were bad in the northeast, insane examples of persecution could be found throughout colonial America. Case in point: the Jersey Devil. Various backstories for the figure exist. Is he the 13th child of a woman who rejected her husband’s authority? Is he the cursed child of a British officer and an American girl? Or is he just the results of a woman straight-up doing rumpy-pumpy with the devil? I don’t know about the Jersey Devil’s origins, but I do know that Weird NJ should thank him for its existence.

Daniel Eskridge/Shutterstock

Religious Superstition Got Worse

Any pretense of being a reasonable nation untouched by the crazier parts of Christianity went out the window the moment we became a country. Furthermore, the American colonists’ improbable victory over the British (with more than a little help from the French) bolstered the religiously-promoted idea of American exceptionalism. If America is God’s chosen nation, then the devil is surely opposed to its success.

This belief system yielded the growth of Evangelism, a uniquely star-spangled way to use religion as an excuse to be a jerk. Evangelism focused on the importance of converting non-believers to the faith, and Satan is definitely not chill with that. One way that Evangelicals believed that the devil interferes with conversion is by possessing human bodies. In this new understanding, witches weren’t necessary to bring Satan to earth; instead of collaborating with evil, those who Christians wanted to ostracize were evil personified. Evangelicals and their ilk were therefore engaged in a constant struggle for souls in which every believer must regularly confront and defeat Satan in all of his forms.

One “Satanic” target for preachers was alcohol. Evangelicals of the time championed the prosperity gospel, believing that those who were successful were God’s favorites. Since liquor interfered with success and therefore with one’s relationship to God, it was viewed as a tool of the devil. Whether the booze was purchased from bootleggers or legitimate brewers and distillers, none of the cash spent on booze was going into the collection plate, a fact that certainly made clergy less enamored with drinking.

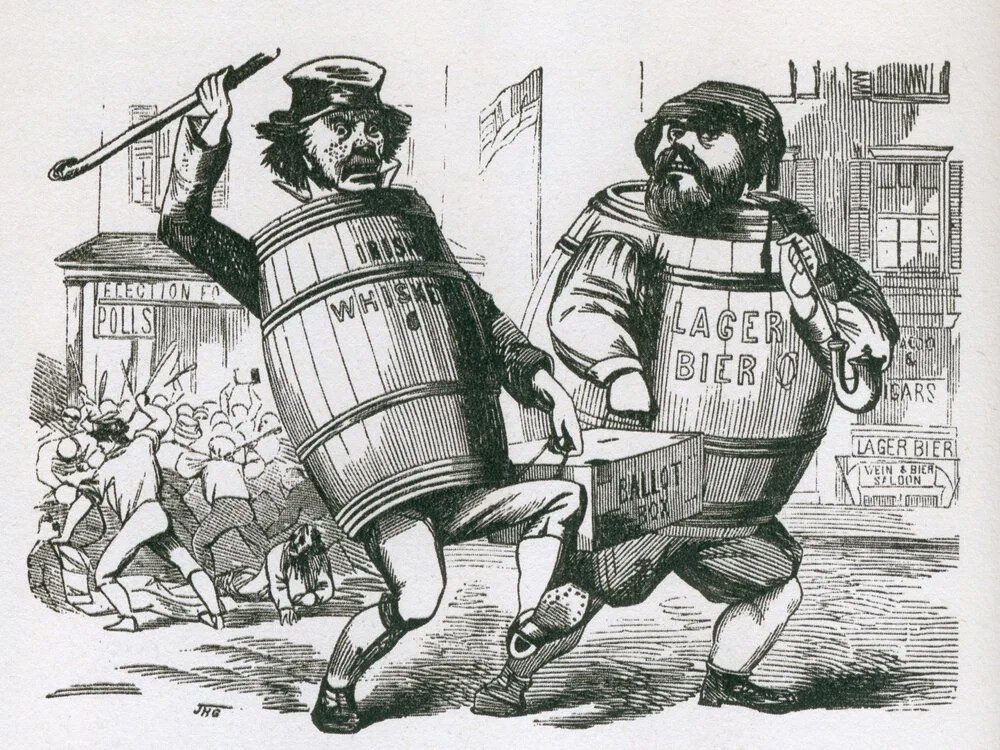

Like all sad stories in America, though, racism was at play here. Catholic immigrants arrived in the United States in waves concurrent with the growth of Evangelism. These recent arrivals were viewed as drunks whose presence destabilized the civil order of the country. These portrayals created a religious case for widespread prejudice against Germans, Irish, and other groups, by foisting a “Satanic” trait on them.

Via Everett Historical Collection

Evangelism experienced a brief death with the Civil War. After all, it’s kind of difficult to talk about spiritual warfare with non-existent demons when your country is experiencing real warfare with physical combatants. However, Americans still found a way to bring the Prince of Darkness into the proceedings. In a particularly noteworthy example, the South Carolina newspaper Keowee Courier had the gall to describe Satan as “the first abolitionist,” trying to link the noble cause of ending slavery with the devil.

If you think that’s breathtakingly stupid, just wait until you hear about the 20th century.

The Last 100 Years

In the early 1900s, many thought leaders from Mainline Protestantism (Episcopal, Methodist, Presbyterian) began incorporating disciplines like literary criticism into their interpretation of the Bible, seeing it not as a sacred document but a historical product of its environment. Likewise, Satan wasn’t a singular being but instead an explanation for conflict in the psyche.

Since they didn’t want anything to do with hoity-toity eggheads, a large portion of parishioners objected to this interpretation. As if Evangelism wasn’t bad enough, the strong desire among conservative Christians for literal interpretation evolved in the 20th century: Pentecostalism and Fundamentalism mixed religion and show business to a degree that was attractive to your average 19th-century American.

Preachers willing to accept their roles as entertainers experienced great success in the period of religious revival that accompanied the rise of Pentecostalism and Fundamentalism. Billy Sunday was one of these preachers who had lay appeal. Born William Ashley Sunday in 1862 (I was shocked to learn that “Billy Sunday” wasn’t just the preacher equivalent of a stripper name), Sunday came to preaching after a career as a major league baseball player. Following an apprenticeship under preacher J. Wilbur Chapman, Sunday started his own ministry where–across his career–he delivered over 20,000 sermons full of slang and colloquialisms that helped him relate to the common man. Sunday–a man whose head looks like a toe plastered with a grimace–gave sermons that were highly physical, featuring smashed chairs and mimed sliding into home plate. A newspaper reporter once called his act “the rawest thing ever put over in Syracuse”; this clearly took place decades before the New York State Fair started featuring butter sculptures.

As his audiences demanded, Sunday offered a literal interpretation of Satan that involved actual contests of strength. He noted that Satan “could pitch with the best of them” and “knocked out more men than all the boxing champions put together.” To drive home the latter point, Sunday would actually act out boxing matches with Beelzebub onstage.

Detroit News Tribune/via Wikimedia Commons

Despite the efforts of Sunday and other preachers to physically destroy the devil, he continued to be a presence in the culture because …

The Devil Has the Best Music

Folk music of this same period was heavily stepped in religion that had a fear of the devil. In particular, gospel music in the early 20th century engaged Satan in terms that were interchangeable with the white man (for obvious reasons). Songs written and performed by African American musicians frequently addressed the figure directly, asking why he hates them and won’t leave them alone. Since white Americans often accused any individuals with darker skin than them of being in the thrall of demonic forces, these songs repurposed hurtful language and imagery.

This therapeutic reclamation reached its apex with the work of guitar virtuoso Robert Johnson, who fused spiritual themes with secular music in songs like “Me and the Devil Blues.”

“Me and the devil

Walking side by side

Me and the devil

Walking side by side

And I'm gonna see my woman

'Til I get satisfied

See see, you don't see why

Like you'a dog me 'round

Say, I don't see why

People dawging me around

Must be that old evil spirit

Drop me down in your ground”

Here we see Satan directly blamed for behavior. Given the legend behind Johnson’s own dealings with the devil, it’s fascinating to see him openly acknowledge how the Prince of Darkness can become tangled up in earthly affairs. Two decades later, bluegrass duo the Louvin Brothers would take the devil’s involvement with everyday life to comic extremes with the album Satan Is Real. First, let’s look at this truly demented album cover:

Capitol Records

You are looking at mandolin player and vocalist Ira Louvin and rhythm guitarist Charlie Louvin standing in front of kerosene-soaked tires and a plywood devil who looks like a slimmer, trimmer version of South Park’s Lucifer. This album cover delivers a clear message about Satan: he is a real presence looming over your life, and he will mess you up if you’re not careful. The album’s title song–in which an old man stands up in church and testifies about his own tangle with the devil–drives that point home:

Satan is real, working in spirit.

You can see him and hear him in this world every day.

When Satan Is Seen on the Silver Screen

The early years of film were also prime ground for exploring America’s fascination with Satan. One of the first portrayals of Satan in moving pictures came with the lost 1918 short, To Hell with the Kaiser. In this bit of World War I propaganda, Kaiser Wilhelm II makes a deal with the devil to enable his continued evil. When he is captured by opposing forces, he commits suicide and goes to hell, where Satan abdicates his throne since the kaiser is more evil and therefore more suited to be the regent of Hades. It’s super weird that Satan’s first appearance involved jobbing to a political figure, but he’s received plenty of additional opportunities to make his mark on celluloid in the century that followed.

The Universal Monsters series of the 1930s to ‘50s provided multiple avatars for Satan to find his way to cinemas. The Wolfman–with his sudden yielding to cravings and appetites he cannot control–provides a perfect facsimile of demonic possession. Frankenstein’s monster’s resurrection shows how arcane powers can control life and death. However, Bela Lugosi’s Dracula is the perfect example of how Satanic archetypes can create memorable movie monsters. The Count is suave and debonair like the ultimate seducer persona that is a part of Satanic mythos. Lugosi’s Hungarian accent lends him an Otherness, and he possesses the ability to control the minds of others. In these ways, the Prince of Darkness was alive and well in the imaginations of moviegoers.

Universal Pictures

This franchise provided the most striking example of Satanic figures on film until cultural shifts of the 1960s and ‘70s yielded more visceral, direct examples. As social tumult of the times–including assassinations and the struggle for Civil Rights–moved to the forefront of public consciousness, Americans turned outward seeking enemies who could be blamed. In 1966, Anton LaVey’s creation of the Church of Satan created a clearer image of organized Satanism in the popular imagination for the first time. Even though Satanists roundly rejected the horrific Manson family murders three years later, this crime brought cult violence into public awareness, and Americans were more-than-willing to label Satan and those who worshipped him as enemies.

One of the most popular films of the era embodied this ethos. The Exorcist addressed concerns about the destruction of the nuclear family by showing how easily Satan can infiltrate a single parent household and possess an innocent child; it’s implied that this infiltration somehow becomes easier when the single parent in question is an actress mom caught up in the concerns of show business. In the end of the film, the female lead finds closure by yielding to patriarchal forces; the devil is ultimately expelled in The Exorcist with the support and sacrifice of priests. In The Exorcist’s world, the only way to deal with change that Americans find horrifying is to retreat into the safety of archaic social structures, indicating the coming conflict between conservatism and Satanism that would culminate in the Satanic Panic (more on that later).

While fear of Satan is heavily steeped in American beliefs and popular culture, some Americans embrace Satanic mythos, forming their religious practice around a figure that many view as the embodiment of evil. Join me tomorrow for the second article of this series, where I’ll trace the evolution of organized Satanism in the United States through the history and beliefs of two organizations: the aforementioned Church of Satan and The Satanic Temple.

You can check out the rest of this series here:

Modern American Satanism: The Church of Satan Vs. The Satanic Temple

4 Ways The Satanic Panic Broke America's Brain In The 1980s

The Cracked Guide To Satanic Rituals

4 Ways America's Satanic Panic Never Really Ended

Top image: Kiselev Andrey Valerevich