The Cracked Guide To The Grateful Dead, Part 1: The 1960s

This week on Cracked, we'll be taking a look at the history of The Grateful Dead, or the band that, through the butterfly effect, inevitably led to Dave Matthews and his cursed, poop-spewing tour bus. Join diehard Dead fan Jordan Hoffman as he lays out the history of the pioneering band.

The Grateful Dead. There’s a real chance that just hearing those words have made you flinch. I get it. Someone in your life—an old roommate, some sketchy friend of an ex that you never quite trusted, that weirdo uncle—doesn’t shut up about this band that’s been retired (kinda) almost as long as they were ever around. The few times you've heard their music it sounded like they were just tuning up, not actually playing, and their zealot fans speak to one another in code, blather about shows from 50 years ago as if they were there, and put infantile stickers of dancing, colorful bears everywhere. Just what the hell is going on here?

Owsley Stanley

Don't Miss

Why the Grateful Dead matter is not something that can be answered too quickly. Not even the stuff about the dancing bears. But to the skeptics, yes, much of it does have to do with drugs, there’s no point denying that. (Especially the bears!) But beyond that, The Dead resonates because they were musical (and cultural) innovators who pitched a very wide tent. Country-rock! Spacey jams! Disco? If you give this group a shot, you will find something in their massive oeuvre to connect with. I swear it. (This is a nice song! Do not deny it.)

In their earliest days of the middle 1960s, one might be drawn to hear simple blues covers stretched out into lengthy jams. At that last gig in July 1995, they were still doing that (Willie Dixon’s “Little Red Rooster” at nearly eight minutes) but also pulling from their repertoire of dirtbag outlaw country (“Cumberland Blues”), exploratory psychedelic forays into time (“Drums”) and space (“Space”), as well as hip-grinding funk (“Shakedown Street”), glassy-eyed emotional anthems (“Box of Rain”), and their one actual radio hit (“Touch of Grey”). They were also (and I know this will sound annoying) the engine of a tribal caravan of people who by-and-large meant well, and certainly inspired a lot of innovation in music, visual arts, and technology. (Some of the very first emails sent via ARPANET from the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory to colleagues at M.I.T. in 1972 were to trade Dead lyrics and setlists.)

None of this was planned.

The Grateful Dead emerged from deep within the San Francisco counterculture of the mid-1960s. Their peers were the Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Big Brother and the Holding Company (featuring Janis Joplin), and, later, Santana. Though never particularly political, they were part of the revolutionary scene, localized at the corners of Haight and Ashbury streets, where, indeed, the band all once lived in one of those old Victorian houses. (It was the site of a well-documented pot bust.)

Like New York’s East Village, this is where freethinkers and beatniks, draft-dodgers, and war protesters gravitated, hung out at free stores, and basically invented “The Sixties,” a concept we’re still grappling with. A few steps from The Dead’s house you’ll find a sizable Ben & Jerry’s ice cream parlor, which ought to tell you what you need to know about what a large part of this all has become. (Yes, Cherry Garcia, which is delicious, is, indeed, named for the band’s central figure, Jerry Garcia.)

Proto versions of the band were known as Mother McRee’s Uptown Jug Champions and the Warlocks. They mirrored the folk revivalism movement that was happening in New York, which plundered from British and Appalachian traditions, but were quick to go outside the lines, mixing frizzy electric guitars and candy-colored keyboards, as well as R&B “rave ups.” (Luckily, Pigpen, one of the lead singers, had a natural swagger that meant a 20-year-old white kid could try and sing like Otis Redding or Wilson Pickett and not embarrass himself too much.)

Their first gig was at a pizza parlor. (Hey, man, did you order mushrooms? Far out!) Then they became mainstays on the scene, which meant playing a lot of ballrooms which were growing dormant until rock acts swept in.

The musical center of the band was one Jerome John Garcia, whose father came from a Galician-Spanish family, played clarinet, and owned taverns. When Jerry was four-years-old his older brother accidentally chopped off most of his middle finger on his right hand. No one can say for sure how much this influenced his eventual, inimitable, lightning bolt-style of guitar playing, and who can blame anyone for not wanting to test it on themselves? Either way, Garcia was a musical omnivore until his dying day, loving free-from jazz, bluegrass, acoustic blues, and even show tunes. His central role in jamming has led to a devotion among listeners with almost no parallel. (Maybe Charlie Parker.) He never played the same lick twice, and the fact that his voice was rich and heartbreaking didn’t hurt either.

Weirdly, Garcia was not exactly the main focus of attention early in the Dead’s history. One could make the case that Pigpen (Ron McKernan) on keyboards, who would strut around to R&B classics (the band called them “rave-ups”) like “Hard To Handle” and “Good Morning Little Schoolgirl” were what grabbed early audiences.

The band had another singer, too, in Bob Weir, who also was a steady rhythm guitar player, laying out unusual chord changes for Garcia to float around. (Music nerds like to compare Weir-Garcia to McCoy Tyner on piano and John Coltrane on sax from the jazz world. Who am I to do otherwise?) Down low was one of the most unique bass players to ever do it, Phil Lesh, who was never satisfied with a simple thump-thump. Lesh plays the bass like a lead instrument, but rarely mirroring Garcia up top. This string sandwich of Garcia-Weir-Lesh is unlike anything else in rock.

On drums, the always in-pocket Bill Kreutzmann maintained a tremendous groove. A couple of years into things Mickey Hart joined as a second drummer, sometimes just doubling Bill to create a four-armed powerhouse of rhythm, but also leading the duo into some of the more elastic, space-ranging explorations into the great beyond. We haven't picked any songs that are long by Grateful Dead standards yet, but you may still want to get a bathroom break in before hitting play.

The Dead made many important connections in those early days, including with concert promoter Bill Graham, but the most important in terms of their lore was someone outside of rock ’n roll: novelist Ken Kesey.

Kesey, a little older than the typical Haight-Ashbury hippie, wrote his signature novel One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest while he was submitting himself for medical and psychological testing as part of Project MKUltra. In short, he got himself whacked-out on LSD at the behest of the United States government. When his book (and subsequent play) made a fortune, he created a retreat out in the woods and threw legendary freakshow parties. These became the fabled “acid tests,” where people would come and open their minds, engage in free love, and have their consciousness scattered to the rim of the galaxy. “Can you pass the acid test?” posters would read, promoting the next gathering somewhere in the Bay Area. (These posters now sell at auction for over ten grand.)

A key element to the acid tests were live music as well as psychedelic lights and films projected on the walls, and the “house band,” so to speak, was the Grateful Dead. Kesey and his Merry Pranksters would also show footage from their “Furthur” trips, in which they rode cross-country in a day-glo painted bus, shocking genteel society with their refusal to bathe and so on. “Mountain Girl” (later Carolyn Garcia, Jerry’s wife) was a fixture “on the bus.” Neal Cassidy, the model for Dean Moriarty in Jack Kerouac’s On The Road was the driver. (He was apparently a very good driver.)

This is also when the Dead met up with scene’s equivalent of Thomas Alva Edison: Owsley Stanley. (We’re getting to the bears.) Owsley became the band’s audio engineer (and logo designer), but of equal importance was his status as an LSD cook. With the nickname “Bear,” his acid was considered the most pure, and one knew that the most likely place to score some was at a Dead show. Furthermore, as tapes of Dead shows began to circulate, enthusiasts began to recognize that, unlike most bootlegs that sounded like they were recorded through a mattress, these recordings actually sounded good.

The first few Dead albums didn’t sell too well. Warner Bros. signed the group trying to get that Haight-Ashbury hubbub to equal dollar signs. While the first three records (especially Anthem of the Sun) had some really cool moments, it wasn’t until 1969 and the release of the double LP Live/Dead that things began to click “off the bus,” so to speak. There it was, side one of four, “Dark Star,” a 23-minute jam way out into orbit, just waiting for open ears and a quiet night.

This is the early Grateful Dead at their peak.

You can find the rest of Cracked's essay series on the Dead here:

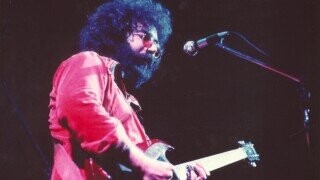

Top image: The Grateful Dead/Dead.net