The Mongols' Secret Weapon: Alcoholic Horse Milk

The Mongol Empire, led by the warlord Genghis Khan, were one of the most dominant military forces in the history of the world. Numerous details contributed to their hugely successful campaigns, including a high level of discipline among their warriors, their prowess both on horseback and in archery, and their flexibility in learning from and utilizing strategies and technology of those they fought against and conquered. At one point, the Mongol empire was in control of over nine million square miles, and a quarter of the world’s population. To even imagine this level of military domination is almost unthinkable in the modern world.

An army this fierce and this large demands sustenance, and sustenance that keeps their spirits high and their bodies strong. One beverage, in particular, was beloved by the Mongols, given great societal importance and even some level of spiritual power. That beverage was airag, also spelled as ayrag. Airag was created by fermenting the milk of the horses traveling with their armies. The finished airag was both high in nutritional value, while also carrying an alcohol content of around 2%. You can see right away how this would be a perfect warrior’s beverage, steeling both body and mind against brutal warfare.

The Mongols certainly didn’t take the power of mare’s milk for granted, as it was a central part of their encampments. After milking their horses, which still sounds like a euphemism for something highly sexual, the milk would be stored in a leather bag inside the Mongol’s yurts, and those entering or exiting the hut would stir the liquid, keeping it agitated to aid in fermentation. The fermentation process would take about two days, and after the rising solids, which were a form of, well, and this sounds wrong but… horse butter, were removed, they were left with a sack of delicious airag, ready to throw back day, night, or whenever in need of a little horsey boost of energy and buzz. There are also reports of warriors keeping a smaller leather bag of mare’s milk attached to their saddle, where the heat of the horse’s body and the movement of the horse’s gait naturally producing a little personal airag supply.

Don't Miss

As the basic stand-up comedy set up would go, “who was the first guy who decided to try that?” Well, the invention and inclusion of airag in the Mongol diet actually gives us some insight into the resourcefulness and self-sufficiency of their armies. The Mongols were a nomadic people, which naturally complicates food sources that farming might provide to a more stationary population. As such, the Mongols were experts at making complete use of every resource available to them. For a people constantly on the move, and known for expert cavalry, that left them with a large amount of horses, and naturally, they looked to put them to their full potential even outside of battle and transportation.

This is where the fermentation likely first came into play, out of necessity rather than ceremony. Horse’s milk is not a very popular libation among humans not only because most people aren’t trying to milk an animal that could kick their head off, but because the milk itself, raw, is a very strong laxative. It doesn’t matter how nutritious something is if you immediately s**t it all out, and I have to imagine no one else in your yurt is too excited about you blowing up the spot either. The fermentation counteracts this, and greatly reduces the lactose content in the milk, another concern for Mongolians, who genetically are predisposed to lactose intolerance. That 2% alcohol content was just a celebrated bonus.

Though I don’t think anyone today, or even in the western world then, was too excited by the prospect of slamming back horse milk, missionaries who tried the beverage actually… kinda loved it? The following is from the writings of William de Rubruquis, who lived with the Mongols for 6 months, describing the taste and effects of airag:

“This cosmos, which is mare’s milk, is made in this wise. When they have got together a great quantity of milk, which is as sweet as cow’s as long as it is fresh, they pour it into a big skin or bottle, and they set to churning it with a stick and when they have beaten it sharply it begins to boil up like new wine and to sour or ferment, and they continue to churn it until they have extracted the butter. Then they taste it, and when it is mildly pungent, they drink it. It is pungent on the tongue like rapé wine when drunk, and when a man has finished drinking, it leaves a taste of milk of almonds on the tongue, and it makes the inner man most joyful and also intoxicates weak heads, and greatly provokes urine.”

Look, nobody wants to milk a horse, but if this is basically almond milk that gives you a buzz and makes you feel strong? I’m surprised tech CEOs aren’t chugging a couple bottles a day like it’s thick horsey kombucha. In a world where bodybuilders are supplementing their gains with breast milk, not to mention the Warrior Lifestyle type marketing you could do, it’s probably only the mental block of knowing you’re sucking on a horse’s nipple once removed that’s stopped it from showing up in Instagram ads.

In Central Asia, though, most likely due to its prominence and respect in the population’s history, airag is still available and beloved today, marketed now as kumis. I don’t think the new name would help it reach western markets, as having the letters kum printed on a bottle of whitish translucent liquid is more likely to get you on r/wtf than on Whole Foods’ shelves.

However, if you find yourself traveling through Kazakshtan, for instance, and you want to try a bit of the fortifying beverage that fueled some of the greatest warriors in history, keep an eye out for bottles of kumis on store shelves, menus, or even being stirred up right in front of you. You may even find yourself presented with a bowl of it as a welcoming gift. Either way, I’m sure locals would be much happier to discuss a vital piece of their heritage than to get asked where Borat lives for the thousandth time.

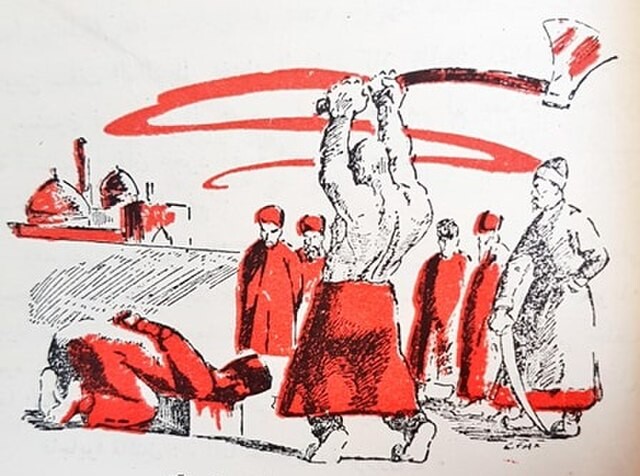

Top Image: Public Domain/takoradee