4 Reasons The Adam West 'Batman' Show Was Complete Madness

For over 80 years, Batman has evolved and changed while still being one of the biggest forces in pop culture. This week, Cracked is doing a deep dive into the Dark Knight.

We're giving away four pieces of art from legendary Batman creatives Alex Ross and Frank Miller courtesy of our friends at The Haul. Enter your email below for a chance to win and learn more here.

Don't Miss

Many people who watched it as kids still talk about how, to them, Adam West's Batman was dead serious. This is a testament to the show's incredible staying power and also of the fact that children are pretty stupid because this thing was utterly bananas. The sound effects, the gadgets, the silly death traps, the absurd clues, the Batusi -- this wacky-ass show made the actual comics from that era look like gritty crime documentaries. How did such a program come to pass, and why are we still talking about it nearly 60 years later? Let's dive in.

A Whole Other Batman Show Became A Pop Art Phenomenon Right Before This One

The Caped Crusader's very first screen adaptation was the not-very-good and yes-very-racist 1943 Batman film serial, in which Batman drove a regular car, operated out of a small cave furnished with a desk and some chairs, and his entire origin was that the government asked him to put on the cowl and help fight the "shifty-eyed J*ps." It was your average war-time film serial, but when it resurfaced 20 years later, those sophisticated '60s audiences thought it was the most hilarious crap ever.

It started in 1965, when the Playboy Theater in Chicago "slapped together" all 15 episodes of the serial and began showing them as a 4-hour movie, and the mostly college-aged audience was entranced by its unintentional campiness. An Evening with Batman and Robin was such a hit that Columbia Pictures began showing it on packed art house cinemas and college towns around the country, hyping it as the "in-tertainment scoop of the year." Critics called it a "new wave Avant-guard pop art classic" and "a 4 1/2 hour Pop Art orgy."

Columbia Pictures

The popular myth states that the serial's success led to the Adam West show, but the show was already in development at that point and its creators never mentioned the serial as an inspiration. At the same time, it's true that the show was originally envisioned as a straightforward crime/adventure serial and shifted into campy insanity at some point. It's possible that the serial's success contributed to that -- especially because some parts seem awfully familiar. Compare the death trap at 2:34 here ...

With the one at 1:04 here ...

Granted, every other building seemed to be outfitted with closing walls and spikes back then, as the second video demonstrates. Then there's the cliffhanger format, which is lifted straight out of film serials (if not this one specifically) and played a big role in the show's success because ...

There Was A Strict Formula Amid The Madness

If you only know this show from its most famous moments, you might get the impression that it was a surrealist fever dream -- just Batman constantly running around with explosives, fighting aquatic animals, and only stopping to perform hit dances. But, when you actually watch the show today, what stands out is how formulaic it was. Most adventures would start with the villain of the week performing a heist of some sort, like this scene from the spin-off movie in which the Penguin sneaks into the United Nations Security Council while cleverly disguised with a mask that renders him unrecognizable.

Next, Commissioner Gordon would call the Batphone and inform Bruce Wayne of the situation, causing Bruce and his young housemate to slide down the Batpoles and change into their work clothes. Batman and Robin would then examine the clues compulsively left by the villain and use their flawless powers of deduction to figure out who is behind it all -- like when Robin, master of logic, deduces that Catwoman must be involved in a crime because it happened at sea, as in "C for Catwoman."

Following their detective work, the intrepid crime-fighters would find the villain and instantly fall into an elaborate deathtrap, leading to the episode's cliffhanger ending. The next episode would start with Batman and Robin escaping the inescapable trap using their incredible wits and skills, such as when Batman calculates the precise pitch he needs to hum at to break the glass in a deadly contraption.

Other times, it's just dumb luck, like when the power goes out as they're about to be zapped by an electric chair and some cops happen to drive by, or when a giant stitching machine happens to hit the exact spot needed to free Batman's hand.

After some more clues and deduction, Batman and Robin would find the villain again and beat them and their identically dressed henchmen in a fight scene so brutal that everyone would hallucinate sound effects in the air due to the brain damage.

This recurrent structure can be seen as a basic precursor to Marvel Studios' winning formula of today: both mix superheroic action and cutting edge special effects (for their time) with plenty of humor and a self-aware tone that constantly winks at the audience, like saying "Yeah, yeah, we know this is ridiculous but isn't it fun?" When you sit down to watch a Marvel movie, you know what you're signing up for. There's something appealing about that, especially during uncertain times. The same applied to this show in the '60s -- most viewers knew Batman and Robin wouldn't be dissolved into acid on the next episode, but watching them punch the same beats like clockwork every week provided a welcome distraction to the wars and assassinated leaders and stuff. And that's precisely why ...

It Turned Batman Into A Cultural Phenomenon (And Probably Saved The Comics)

By the '60s, Batman was a famous character but not the ever-present icon we know now. Sales of the comics had fallen so drastically that, according to co-creator Bob Kane, DC was "planning to kill Batman off altogether." In fact, in an attempt to save the comic, in 1964 DC assigned a new editor to get rid of the sillier elements and create more realistic stories ...

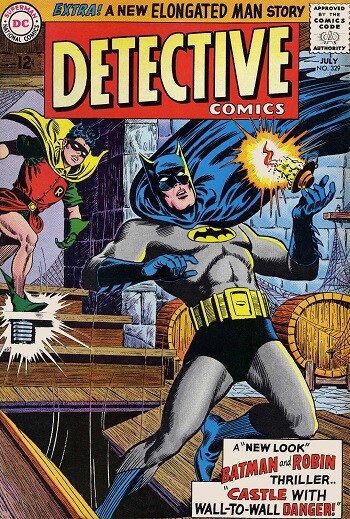

DC Comics

... until Adam West swung in and pushed the entire franchise into the opposite direction.

DC Comics

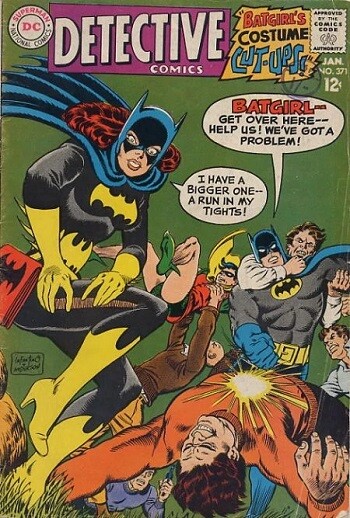

Not only did the stories become sillier again, but DC began reprinting some of the wackiest issues of yesteryear to appeal to their new readers. The Adam West effect caused sales to explode to pre-1950s moral scare levels, not just for Batman comics but for DC titles in general (and other companies to a lesser degree). Many long time fans weren't too happy about the sudden shift to a campier tone, but the show did lead to some positive and long-lasting changes -- chief among them being the most popular version of Batgirl, who debuted in the comic but was created for the specific purpose of turning the show into less of a sausage fest in its third season.

DC Comics

The show also reshaped Batman's Rogues Gallery in a permanent way. Enemies like Catwoman had fallen off the radar for over a decade and others like Riddler and Mr. Freeze (or "Mr. Zero" as he was known before the show) had made very few appearances before their TV versions turned them into pop culture icons. The Riddler even got a hit song, as did the Penguin and Batman and Robin themselves.

In 1966 alone, the Batman show moved over $75 million in merch, more than doubling James Bond's numbers. The Batmania fad was sweeping the world -- and then, like all fads, it ended once the show got canceled, and it all went down the drain, including comic book sales. But that doesn't mean the show's influence was over ...

It Directly Influenced The Movies (Even The Darker Ones)

After trying to distance himself from his Batman image for years, Adam West sorta gave up on that front in 1977 and went into a perpetual "revival" mode that lasted until his death in 2017. He and Burt Ward reprised their characters in cartoons, an even nuttier live-action Super Friends special ...

... various ads and special appearances, a semi-autobiographic TV movie, and two animated sequel films. The Batman cinematic franchise went through a similar process, in that the more they tried to pull away from the show's campy tone by going all dark and gritty, the less they could resist the pull of its influence. Batman Returns borrowed its basic plot from a two-part episode about the Penguin running for mayor of Gotham, which was also adapted in a season of Fox's Gotham. Batman Forever had Val Kilmer use a bit of Adam West-esque Bat logic to solve the Jim Carrey Riddler's clues:

Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight paid homage to the Cesar Romero version of the Joker via the clown masks used by the Joker's goons in the opening.

Speaking of Joker, the Joaquin Phoenix movie showed little Bruce Wayne sliding down a metal pole as a confirmed shout-out to Adam West and his probably calloused hands.

So don't be surprised if The Batman ends with Robert Pattinson punching some criminals with the words "BIFF!" and "POW!" materializing in the air. It would be a justified homage to the show that rescued the franchise from certain doom.

Follow Maxwell Yezpitelok's heroic effort to read and comment on every '90s Superman comic at Superman86to99.tumblr.com.

Top image: 20th Century Television