Every Studio Ghibli Film Is Secretly About The Same Thing

We're giving away four pieces of art from legendary Batman creatives Alex Ross and Frank Miller courtesy of our friends at The Haul. Enter your email below for a chance to win and learn more here.

In the past few years on this here Internet, there's been a sort of subculture congealing around the vague concept of "wholesomeness," and it absolutely totally sucks. I am not exaggerating when I say I would rather fight the pack of rabid coyotes that live in the abandoned K-Mart parking lot than have to see one more post about what an epic wholesome good boi Mr. Rogers was.

Don't Miss

Even worse, this wholesomeness movement birthed a submovement devoted to fawning over films, TV, books, and video games that are thought to be "cozy" and "free of conflict." Studio Ghibli movies are often brought under this regressive umbrella, and that's crossing a line where I can't stay silent any longer. Describing the films of Hayao Miyazaki as being free of conflict conjures within me such a deep well of loathing and frustration.

Because Studio Ghibli movies aren't free from conflict. They're about as free of conflict as a Black Friday Ham Sale at a Midwestern Ham-Mart. But audiences, particularly American audiences, seem to be incapable of conceiving of the conflict inherent in his films. Not unlike how an H.P. Lovecraft protagonist can't perceive a really big fish dude or how Los Angeles drivers see only a shimmering grayish mist where the rest of us see a turn signal lever.

I'm sure you're all excited to hear me shriek about how everyone is watching anime wrong, reeeeeee, but first, a quick note: I'm going to be talking specifically about the films of Hayao Miyazaki. I'm not going to be talking about The Cat Returns, and I'm definitely not going to be talking about Earwig and the Witch—I'm much more comfortable believing the latter was simply a hallucination brought on by a debilitating brain parasite I contracted from Chipotle rather than a grim look into the future of Studio Ghibli. At least it's comforting to know the American film industry isn't the only one being ruined by nepotism?

So What's The Conflict?

In most of Miyazaki's work, there's a recurring conflict in some form or another. Sometimes it's fairly explicit and central to the plot, and sometimes it's more subtle and hidden in the background. It's the conflict between everything that's true, good, and beautiful in the world … and capitalism.

Ghibli Store

I know, I know. Huge shocker: the obnoxious lefty comedy writer thinks that some of the greatest films ever made are actually all about how socialism is good, you guys; you just don't realize it. And look—my purpose here is not to change your political opinion; it's just to help you see Miyazaki's. Which is, again, that capitalism is antithetical to everything good in the human soul. I understand if you're skeptical of this, partially because Miyazaki's films are so damn good, they can be deeply enjoyed and appreciated even without this understanding. Miyazaki's personal politics are often described as "humanist," "idealistic," or "hopeful," but these are all either intentional euphemisms or a misunderstanding. For many years, Miyazaki considered himself a Marxist. Once I learned that, I started to see it everywhere in his films.

While Miyazaki no longer considers himself a Marxist—Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was partially written as an expression of his despair at the ultimate failure of the Soviet Union—I think it's more than fair to say that he's still at least anti-capitalist. He's some sort of, I don't know, eco-agrarian collectivist? The ongoing motif of his films, besides that aircraft are neat, is that capitalism saps the wonderment from the world and leads to the spiritual diminishment of humanity.

Ponyo is about the daughter of a foppish ocean wizard so disgusted with pollution he actively wants humanity to be destroyed. Princess Mononoke is about industrialization killing unknowable forest gods. Pom Poko is about tanukis fighting deforestation using their magical ballsacks—if you thought for one second that just because Miyazaki didn't write or direct that one it meant I would resist the temptation to write a sentence containing the words "magical ballsacks," then I'd like to thank you for choosing this column as the first thing you've ever read by me. Nice to meet you!

Studio Ghibli

Perhaps where Miyazaki's anti-capitalist tendencies are most obvious is in Spirited Away, a movie so good that by comparison, it makes The Godfather seem like The Godfather 3 and The Godfather 3 seem like Tyler Perry Presents Madea: On Trial at the Hague. Spirited Away is so rife with symbolism about Miyazaki's belief in the dehumanizing effect of capitalism that someone much smarter and less lazy than me could probably write an entire book on it, but for now, we'll have to settle for a few examples. To start, consider the film's setting:

Studio Ghibli

The bathhouse is beautiful, elaborate, tempting—but we see firsthand that it operates by having a workforce that is paid virtually nothing if anything at all. When we first meet Kamaji, the freaky Dr. Robotnik-ass six-armed boiler man, he describes himself as "a slave to the boiler that heats the bath." He also tells the adorable little soot sprites that if they stop working, the magic that gives them life will wear off. The message is clear: here, you produce value, or you die.

And the person taking all of this value is Yubaba, the cruel witch. Her quarters at the top of the bathhouse are ornate and luxurious, a far cry from the squalor from which the employees live. It might also be worth noting that her quarters are the only part of the bathhouse decorated in a Western-style.

Studio Ghibli

When Chihiro, the film's protagonist, first encounters Yubaba here, she agrees to work at the bathhouse. After Chihiro signs a contract, Yubaba literally steals Chihiro's name, renaming her "Sen"—which is Japanese for "one thousand." In a moment, so on-the-nose it would make Oliver "Nixon Has Blood On His Hands Haha Get It?" Stone blush, Chihiro literally becomes a number, losing her humanity. Later in the film, she struggles to remember her parents and her past after becoming Sen. Miyazaki once said, "We lose feelings of reality when we work for the numbers," and the dreamlike world of Spirited Away has an amnesiac effect that represents this. Living in that world, it becomes impossible to imagine something different, something better.

Speaking of amnesia, Spirited Away has more than a 90s soap opera. Chihiro slowly forgets who she is. Her parents, unable to sate their desire to consume endlessly, literally turn into pigs (whom Yubaba plans to slaughter—the consumer existing to support the consumption). Haku, a water god, forgets himself until Chihiro spurs his memory. A river spirit comes to the bathhouse but is so choked with filth and pollution that he's forgotten who he is and becomes a disgusting ball of shambling filth known as the Stink Spirit, which is also a description of every roommate I've ever had. Even Yubaba isn't exempt—in her greed, she doesn't realize that her gigantic baby has been replaced until Haku prompts her.

Of course, if we're talking about how the bathhouse makes people lose their souls, we have to talk about No Face, winner of 2002's Most Nightmares Caused Award, right behind Possibility of 9/11 2 and perennial contender Toilet Snakes. No Face seems to lack a sense of self, and like a preteen in a Hot Topic, he simply absorbs everything around him to form a simulacrum of personality. In the bathhouse, this means he becomes greedy, lonely, and all-consuming. He's never satiated. No matter how much he's given, he always wants more.

Studio Ghibli

Only Chihiro rejects his offer of money, and not being able to coerce someone with money throws him into a confused rage like a Boomer McDonald's manager angrily writing "no1 wants 2 work ennymore!" on Facebook.

No Face is only brought back to sanity when he follows Chihiro to the hut of Zeniba, Yubaba's older sister and opposite. Zeniba lives in a wattle-and-daub hut. It's meant to be the apotheosis of modesty, but to my millennial eyes, owning property at all seems like just as much of an outrageous fantasy as a theme park bathhouse populated by spirits. In this humble setting, where Zeniba seems to make everything by hand, No Face becomes calm, helpful, and fulfilled—he's found meaning in working for people he knows.

In perhaps the most important scene in the film, Zeniba and No Face, along with help from Yubaba's gigantic baby and one of her transformed minions, weave Chihiro a hair tie. "It will protect you," says Zeniba. "It's made from the threads your friends wove together." To quote Led Zeppelin, "sometimes words have two meanings." The threads are literally woven together to make a stronger whole, but the hair tie is also a product of cooperation from Chihiro's friends working in concert.

And sure enough, at the end of the film, the hairband glimmers just as Chihiro is tempted to look back at the Spirit World, which would have trapped her forever. Cooperative, collective labor is what saves her from the illusory promises of the Spirit World.

Studio Ghibli

So Why Don't People Get That The Conflict Is "Against Capitalism?"

To varying degrees, with Spirited Away being the most and My Neighbor Totoro being the least, I think it's fair to say that the antagonistic forces in Miyazaki's films, the sources of conflict, either are, or are representative of, capitalism. So why do American audiences see his films as "conflict-free," besides corn syrup brain? I think there are three reasons.

The first is that Miyazaki is a deeply empathetic man—he wouldn't be much of a leftist if he wasn't. He's not interested in making a one-dimensional polemic on the Evils of Capitalism. Consider that in Princess Mononoke, Lady Eboshi, the de facto leader of Iron Town whose pollution and expansionism are driving the forest gods insane, also cares for the town's lepers. She cares for the sick because Miyazaki gives villains more moral credibility than their real-life counterparts.

Studio Ghibli

The second reason is that, at least in the United States, we're so inundated by capitalism that recognizing criticism is impossible if we don't even realize there's an alternative. Just look at how interchangeably "liberal" and "leftist" are used in some American political circles. Look how meaningless the word "socialist" has become if your most racist uncle uses it to describe Joe Biden, a man so deeply conservative he gave the eulogy for Strom Thurmond. It's as meaningless a phrase as "new and improved," "on the blockchain," and "no, William, I won't ever make fun of your weird feet." It's a conflict so gigantic, something we're so immersed in, it feels invisible. Phrased another way: does a fish feel wet? If you were born in the Piss Factory, is there ever a time when you're like, "Hey, it smells like piss in here?"

But I think the biggest reason is that American audiences are simply unequipped to understand leftist films because they're such a rarity in the US film market. Despite the completely incorrect reputation Hollywood has as being a bastion of commies thanking Stalin when they win the Oscar for 'Film That Most Hates America (Live Action),' there are very, very few mainstream leftist voices in contemporary cinema.

In fact, Miyazaki is almost certainly the most known leftist voice in the film industry. Outside of him, there's, uh … Adam McKay is a fellow DSA member, so him, and uh … oh! Bong Joon-ho, for sure! Is Boots Riley considered mainstream? No? What about Werner Herzog? Michael Moore is mainstream-adjacent; what's he been up to? Other than that, umm … there's, uh … Alfonso Cuarón snuck a hammer and sickle into Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, does that count?

Warner Bros.

Ultimately, audiences failing to see Miyazaki's critiques of capitalism (or seeing them only as hippy-dippy milquetoast pro-environmentalism) says more about audiences than it does about Miyazaki himself. Perhaps the movie he makes the next time he comes out of retirement, the Super Duper Last Movie He'll Ever Make For Real This Time You Guys, will be received by an American audience that's become more receptive to his ideas. Maybe he'll be less subtle this time.

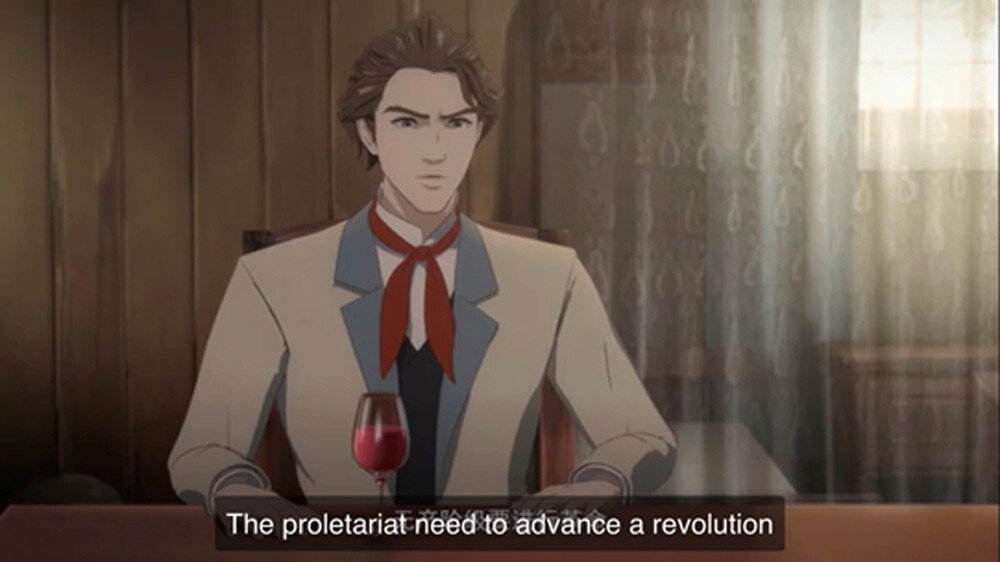

Bilibili

Or maybe, just maybe, if we can make the American film industry more accessible to those who don't come from wealth and connections, those who graduated with honors from the University of Don't You Know Who My Father Is, we'll see more films made by those with firsthand knowledge of what it's like to live in a world where most of what you make is taken by those who already have more than you ever will.

William Kuechenberg is a repped screenwriter, a Nicholl Top 50 Finalist, and an award-winning filmmaker. If you’re interested in having more leftist voices in the film industry, consider hiring him to be a writer or writer’s assistant on your television show! You can also view his mind-diarrhea on Twitter.

Top image: Studio Ghibli