In The Middle Ages, Reading Was More Complicated Than We Think

Certain things in the recent era can feel akin to the Middle Ages … or at least what we think of the Middle Ages. The truth is a lot of what pop-culture presents of the period doesn't match the actual history. This week at Cracked, we're doing a Middle Ages deep-dive – the good, the bad, and the ugly.

To oversimplify and generalize history, the idea behind the "Dark Ages" is that after the collapse of Rome, much of Europe fell into a period of cultural regression. Literacy, in general, was lower in medieval Europe than in Rome, with things like graffiti in Pompeii highlighting how it wasn't restricted to certain social classes. After the fall of Rome, though, there is not much to show people beyond higher social rankings demonstrating this causal level of literacy.

Estimates vary on literacy rates in the Middle Ages, and because we're talking about a period that spans centuries, there was a lot of fluctuation. However, it is known that peasants typically didn't read or write. The education that they did receive was less formal and focused on learning skills relevant to the jobs they would do. Even if a peasant wanted to go to a formal school, they faced several hurdles. Serfs had to have permission to attend school from their lord, and even if they got permission, schools were prohibitively expensive.

Don't Miss

One important thing to note when talking about medieval literacy is that they went by a different definition of "literate." This is a word that even today isn't universal. Is someone literate if they can read but can't write? In medieval times, being literate meant that a person could read and write Latin. People often learned to read and write their vernacular languages, but being "literate" was a matter of knowing Latin, the high-class language.

So, with (some of) the logistics out of the way, if someone could read, what did they read?

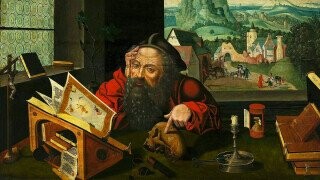

Religious texts were important throughout the Middle Ages. This was true for clergy and laypeople alike. Monks and nuns were expected to spend their days praying and studying, and texts played a role in this. This included reading from the Bible as well as writings from scholars. Even for those not living that monk life, Psalms and other religious texts were still common reading material.

This wasn't all of the material available to medieval readers, though. They also had much more exciting options like royal charters, petitions, and other legal information. Yes, those who lived in cities, unlike agricultural peasants, had plenty of practical reasons to know how to read and write. Being able to understand a document could help a merchant in his business dealings, for example.

That part about literacy revolving around Latin wasn't just to be pretentious either. It also had a practical effect throughout Europe. Knowing Latin meant that it was easier for information to travel across Europe. Particularly before the printing press, Latin was the most common language for printed text, so knowing Latin meant having access to more information throughout the continent. That merchant who used his knowledge of reading and writing to document his business would have a wider possible market because Latin crossed borders.

Okay, so religious texts and legal documents are about what you'd expect people in medieval times to read. Now, let's turn to something spicier (for real this time): poetry about longing for married women.

It isn't surprising to learn that much of the Middle Ages literature was based in the courts of nobles, people who had the time and resources to focus on poetry. Beginning in the 11th century, troubadours traveled the courts of France and spread across the region. Troubadours were poets and performers, and their revolutionary genre of poetry is known as courtly love.

Courtly love is the basis for a lot of our modern-day understanding of medieval life. It was a genre that focused on knights, and this led to a more refined version of Arthurian legend. What courtly love truly focused on, though, was a knight's devotion to a woman, especially a woman who was beyond their reach. This could mean that a woman was already married or was simply too far away geographically.

These poems were not necessarily “read,” as they were performed by troubadours to nobles. This meant that a troubadour would recite verses about longing for a woman they could not be with, and they would do so directly to a woman who was likely married and realistically was probably not happy in said marriage. Courtly love challenged conventions because marriage in medieval times was done for mostly practical reasons, and “love” as we know it was ignored. Through these poems, though, people got a taste of the types of love they couldn’t get in real life. Again, this was some scandalous stuff for the time.

For a vast majority of people in the Middle Ages, reading wasn’t even on their radar. Learning how to read did become more common, though, and literacy climbed as the medieval period wound down. Gutenberg’s printing press made it much easier to produce texts, which meant that more people had access to reading materials. Literacy rates never became perfect, but more people got to experience literature other than bored noblewomen who paid a performer to recite love poems to them.

Top image: Amant Molet