5 Film Myths That Snobs Believe

While the internet spreads silly stories about munchkins hanging themselves or Stanley Kubrick faking the Moon landing, aspiring filmmakers go to school to learn slightly more esoteric rubbish. Leave it to cinephiles and journalists to spin tales more fanciful that a lot of professional screenwriters are capable of. Starting with …

Myth: "Shaky Cam" Adds Realism

If you've witnessed a piece of mainstream entertainment in the last decade you’ve likely wondered why characters inexplicably break the fourth wall like they are schizophrenics talking to the invisible people in the living room wall, the camera jittering uncontrollably through the awkward pauses:

You can’t hear the laugh track because it’s in their heads.

The trope goes way deeper than sitcom mockumentaries. Blame out-of-touch, pretentious Danes. The Dogme 95 film movement eschewed certain techniques, genres, and equipment. Basically, they thought all films should look like documentaries. Tripods were forbidden, and the director was uncredited. If it didn't look like your dad recording your fifth birthday party you could never be taken seriously by real auteurs.

From the arthouse, it inexplicably trickled down to action films, sitcoms, and video games. GTA V’s cut scenes more closely resembling an Office episode than it does a gritty heist movie:

Squint and you can make out Dwight, Jim, and Pam.

Here's the problem. You don't notice a stationary camera. That’s the point of a tripod. Shaky cam draws attention to the filming technique and to the camera and director. In modern films it replaces directorial style rather than complementing it. Anyone who's seen a Bourne movie will be thinking less about the plot than why the camera dude was holding the camera with one arm while chugging a beer with his other:

Chasing it with a shot of Dramamine.

It’s perpetuated on a lie. The human brain can sort out jerky movements, visual distractions, jolts, and swaying … just not when it’s on a screen. The organ is so adept at conveying a smooth image it can even learn to adapt to being upside down. The human eye may operate on the same principle as a camera lens, but the final image we "see" in our brains is more like footage from a professional Steadicam than a drunk Tik Tokker recording herself on an iPhone.

Myth: Oscar Bait Is A Desperate, New Gimmick

There's no Academy Awards without Oscar-bait. Films about tragedies, murdered social reformers, disabled people, or other marginalized historical figures grab awards like honey attracting flies. We're left reminiscing for a purer, more innocent time when Hollywood was simply interested in making plain, ol’ good movies.

That time never existed. In past years, “prestige pictures” were packed with a couple bankable, trustworthy stars, larded with lavish sets, and usually employed the best writers. Often they were based on successful novels, the fledgling industry deciding to focus on rewarding films showcasing profound social merit and epic romances:

“Oscar bait” was once used without stigma. The nineties had AIDS and mental-disability Oscar bait. The fifties had PTSD and disfigurement-themes to lure in voters. Hollywood was glutted by historical biopics, boring epics, and stilted, nuance-free films that didn't experiment or confuse mainstream audiences. Should sound familiar. The more mawkish, the better. Modern directors are just copying the classic model, pulling old established Oscar formulas out of the trash to recycle.

Fifty years before scumbag Harvey Weinstein used disabled-rights advocacy as a prop to promote his film about a painter, stars were taking out embarrassing ads and staging dumb stunts in PR events. Yup, there truly are no original ideas left in Hollywood.

Myth: Jump Cuts Were A Masterstroke From A Daring Genius

À Bout de Souffle, better known as Breathless, is arguably one of the most important films ever made. Its director and writer, Jean-Luc Godard, is responsible for the jump cut. Rather than using dissolves or smooth transitions, the film reel was cut giving the audience no warning of jarring shifts in time. Common now, it blew minds in the sixties.

No, your wi-fi isn’t being drained by your deadbeat neighbors, the movie is supposed to look choppy.

Abrupt edits were not a stylish innovation as film historians like to think, deliberately created to express a certain attitude or pace. It was a last-ditch, defensive blunder to salvage a bloated rough cut by a director with no experience whatsoever. Thus, an amateur’s homage to B-movies shot with no permits, blocking, or set preparation (every pedestrian gaping directly at the camera) became remembered as an avant-garde tour de force.

To trim down the runtime, Godard hacked chunks off every scene. Continuity mistakes were ignored out of necessity, and the editing couldn’t fix them. Godard shrugged and said “screw it.” The jump cut was born. Because everyone was accustomed to films and TV productions made only by disciplined professionals, they assumed it must be a calculated, deconstructionist “experiment.” It’s not unlike an art expert mistaking a red crayon doodle on a canvas as a masterpiece.

Godard knew better, the French director fessing up to the movie being a complete mess and insinuating he would have made it differently if he had the time and experience to know better. That’s about all we know, as he broke out in screaming fits when reporters broached the subject, threatening to burn all the existing prints of his career-defining movie. We’re gonna go out on a limb and say he was not a fan of the technique he immortalized.

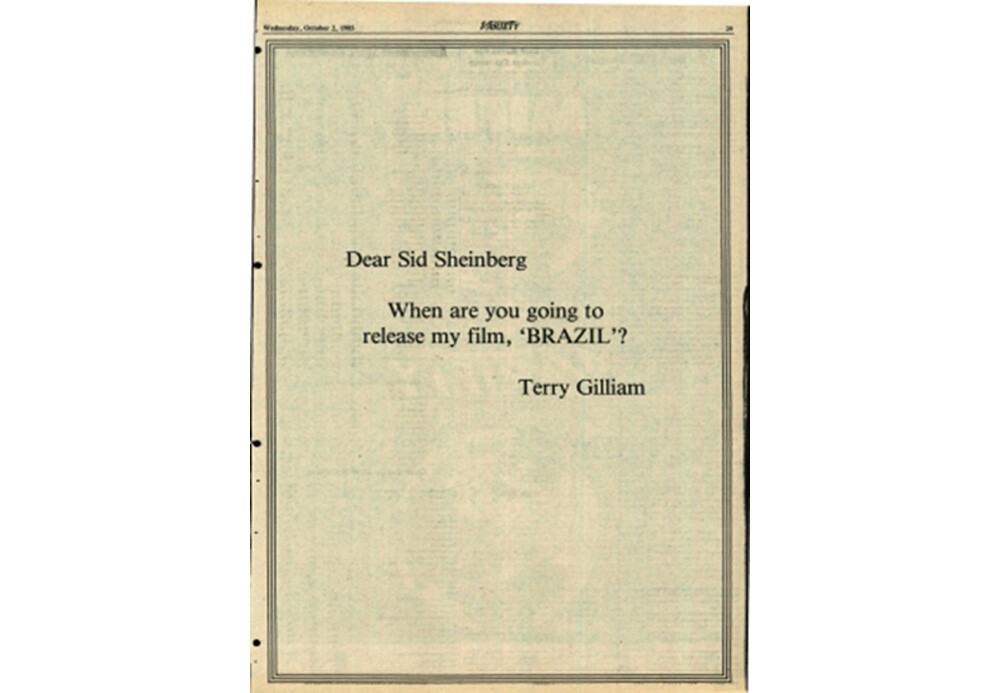

Myth: Universal Had No Right To Shelve Brazil

Terry Gilliam's Brazil is as famous for the PR fiasco surrounding its release as for its writing. For months, Universal refused to show it domestically, deeming it too long and self-indulgent, compelling Gilliam to take out a passive aggressive ad in the magazine Variety harassing the studio, full-on David vs Goliath. Consider it the first social-media spat:

Variety

Brazil was greenlit after Gilliam promised a contemporary iteration of Nineteen Eighty-Four just in time to maximize marketing potential in the year 1984, the writer/director gushing it was "Nineteen Eighty-Four for 1984," "a post-Orwellian view of a pre-Orwellian world."

One huge problem: Gilliam had absolutely no idea what the hell he was talking about. He never read the book, explaining why the film only borrows a few stray, superficial elements from the novel. In the book, Winston Smith rages against a degenerated communist regime. Brazil's hero is motivated by a hatred of paperwork and plastic surgery. Orwell explores how language is used as a tool to alter thinking and dissolve reality. Gilliam’s film is about typos. Co-writer Tom Stoppard was irritated and confused at the meandering, ambiguous script. So was Universal, the people Gilliam had duped with his bogus elevator pitch. The Apple Super Bowl ad was more faithful to the spirit of the book:

Who understands misinformation and censorship better than Apple?

This film had train wreck written all over it. Stoppard jumped ship after an earlier collaborator on the project, Charles Alverson, bailed months before. Alverson's usually written out of the production's lore, ostly because Gilliam spent twenty something years trying to screw him out of writing credits.

You can see why the studio execs bailed too. No one on set had confidence in or understood the film, especially the people writing it. A faithful adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four had just beaten them into theaters. Universal's hunch was accurate; Brazil’s international gross from opening weekend didn't even cover the catering budget. Universal cut their losses. Shocking as it seems, that’s not uncommon.

Myth: “Serious” Filmmakers Use Black And White

Want to communicate to your audience that a film is important? Black and white. Need to convey misery? Black and white! Need to get noticed by award voters and have no marketing budget? Ditch color, you pleb.

No better time to be a movie fan or color blind.

Usually, black and white is used as a visual homage to the 1890s -1960s, a nod to archaic photography. Simple enough.

But why would a movie set before photography like A Field in England use it? To allude to woodcuts? Why is a hipster romcom like Frances Ha set in the modern-day shot in monochrome? To allude to Snapchat filters? Why is Fury Road's DVD release, a post-apocalyptic sequel based on vibrant color films from the seventies & eighties, converted into black and white like it’s an obscure Ingmar Bergman flick? Did the guy who made the James Bond origin story realize the original Connery films were all in color? Why is The Human Centipede 2 pretending it is an NYU film-school project from 1979?

Not until the nineties did the artistic (and financial) value of black and white become apparent with Jim Jarmusch’s quirky indies and Kevin Smith's Clerks. Ironically, Kevin Smith only made Clerks in grayscale because of crappy lighting sources. Color film used to be expensive, and so were color grading and lighting guys. Nowadays, color footage is painstakingly turned black and white. If Smith wasn’t making a black comedy about necrophilia he might have secured a bigger budget and used color.

Hey, corpse makeup is expensive.

No self-respecting filmmaker wanted to use it. Until now, that is. The lo-fi, outsider aesthetic is officially dead. In 2021, the effect just looks cynical. Yes, your uber-serious movie about kung-fu-fighting CGI cyborgs looks like Citizen Kane, so does every cornball perfume ad made since 1992. At this rate we’re surprised Snoop didn’t get an Osacr nomination for Best Short Film:

Top image: Warner Bros.