5 Big Jobs That Movies And TV Get All Wrong

Look, no one's expecting movies and television shows and books to get everything right about everything—it's called entertainment for a reason. If you don't want creatives to be creative, go read an encyclopedia, nerd. Being forced to actually learn is only fun when there are Muppets involved.

Still, you'd think that, maybe, the Hollywood-industrial complex would have at least some notion, however fleeting, about how the careers most prominently featured on our screens actually function. Instead, the most basic components of certain jobs are wildly misrepresented, episode after episode, season after season, generically named procedural after generically named procedural. They might as well be made up from whole cloth, like space cowboy or radioactive lizard wrangler or responsible congressperson …

Homicide Cops Work Significantly Fewer Cases Than You Think

Everyone loves cop shows—even people who hate cops. Turn on your TV or fire up your cellular telephonic device, and there's a new unsolved homicide every episode on all the Law & Orders, CSIs, and early seasons of the Lucifereses. "Murder of the week" is its very own genre; literally, a new mysterious death every episode is the whole draw.

Don't Miss

Meanwhile, in the real world, the average homicide detective works, maybe, five cases annually. That's not a typo: five cases. Enough that, if a person still had all their fingers, they could hold a coffee mug in one hand and count all the corpses with the other. Hell, in Detroit, routinely one of the most stab-happy places in the United States, homicide detectives only average eight cases a year. And that's considered too many.

AMC

You see, detectives with more than four cases per year struggle to successfully solve those cases, with arrest rates of less than 50%. A single season of Sexy Murder Cops: Dubuque would be enough to fill an entire real-world detective's career with a crime-to-arrest ratio that would be mind-bogglingly legendary—and/or bring internal affairs sniffing around for fabricating CompStat numbers.

In fact, Vernon Geberth, a former N.Y.P.D. detective, current homicide consultant, and guy who wrote books and trains detectives nationwide, has said, flat-out, that in any given year, "even the best detective can't handle more than five cases."

CBS

Also? Clearance rates for homicides are, at best, around 70%. Big cities—like where all those cop shows take place—are closer to 50%. Meaning that, on average, every other murder goes unsolved, or at least unarrested. But watching the hero spend thirteen episodes doing paperwork and making phone calls and then still not getting anywhere would probably be kind of depressing.

Blood Spatter Analysis Isn’t Reliable

Julie Finlay of CSI: Crime Scene Investigation and Dexter Morgan of the Dexter books and TV show(s) are both blood spatter analysts, renowned for their ability to look at a Jackson Pollock painting made entirely of bodily fluids and figure out who murdered whom and where and how. The technique has even shown up on shows like Brooklyn Nine-Nine as a crucial investigative tool so faultless it's akin to magic.

The only problem is that blood spatter analysis is kind of full of crap.

Showtime

In 2009, the National Academy of Sciences—yes, that National Academy of Sciences—published a report explaining that "the uncertainties associated with bloodstain pattern analysis are enormous." Then, to really drive the point home, they said that all that "expert" analysis was "more subjective than scientific." Which, given that the entire practice started in some dude's basement in the 1960s, makes sense.

Herbert MacDonell, former community college teacher, glassware chemist, and possible vampire, got a grant from the Department of Justice to study sprayed murder-blood, published a paper, and then started theatrically hawking his findings like—as a lawyer once derisively called him—Mr. Wizard. Despite that particular lawyer's complaints and MacDonell's own assertions that the practice wasn't entirely accurate, the legal system was hooked.

MacDonell started teaching other people, who then started teaching other other people, eventually culminating in a standardized 40-hour workshop that could certify anyone as a blood spatter analyst. But, as that NAS report asserted, one workweek isn't nearly enough time for anyone to actually get good at blood spatter analysis.

To accurately "read" bloodstains, you need an understanding of "applied mathematics, significant figures, the physics of fluid transfer, and the pathology of wounds"—none of which are covered in the workshop. Nor could they be. Seriously, ask anyone who took multiple years of college calculus but still needs a calculator to figure out a tip how good they are at applied mathematics.

CBS

As a result, blood spatter analysis is almost entirely unobjective, with most further advances in the practice coming from non-scientists. Rather than numbers and physics, it's based on "experiences, anecdotes, and empirical observations." As Suzanne Bell, a forensics expert at West Virginia University, explained: "To get their data, analysts would walk into a room, fill a sponge with blood, and hit it." Which, in case you need the reminder, is not how human people work.

To be fair, following that bombshell report, actual scientists have set to work trying to fix things and make the practice more reliable. In the meantime, though, despite all the inaccuracies and unfair imprisonments and countless screaming hematologists, blood spatter analysis does still hold up pretty well in court. Of course, a large part of why juries buy into it is because they saw it on TV, and TV is basically just coasting on all that Mr. Wizard bullshit, so it's basically an ouroboros of criminal injustice.

Lawyers Aren't General Service (And Work With A Team Of Hundreds)

We've talked before about the countless ways that Hollywood lawyers are terrible at being lawyers, but, like any good morally dubious huckster, that's not all.

Tune in to The Good Fight or Suits or—and may Kim Wexler's ponytail forgive us for saying this—Better Call Saul, and you might notice that lawyers and law firms seem fully capable of helping literally anybody with anything at any time. TV lawyers never have specializations or help. A single individual will take on divorce and immigration, or criminal law and corporate real estate, with maybe a paralegal or one other lawyer (that they're usually boning) assisting.

CBS

That is 100% the wrong way to be a lawyer. If some dude walked up to you and said he could help you with your divorce and your car accident and your lawsuit against Disney for stealing your idea for Mickey Mouse Does Dallas, and that he could do it all by himself, you would laugh in his face and then probably run away before he asked you for a dollar for a cup of coffee because there's no way that guy wouldn't be broke off his ass.

The most successful and reputable law firms are gigantic, filled with different teams of different specialized expertise. People who are experts in their one, very specific field—and, sometimes, in even more specific subsidiary fields within those first fields. And, yes, okay, some lawyers might work in maybe two or three closely-related areas at once, but that's it. Bouncing from family law to intellectual property law to medical malpractice from one week to the next is untenable. No one person could be any good at all of that.

20th Television

Which, again, they aren't (thereby throwing the entire oeuvre of John Grisham, Erin Brockovich, and pretty much all movie lawyers onto the blame pile, too). In real life, cases are worked by teams of lawyers—and paralegals and legal assistants, and technical specialists and bookkeepers and records clerks, any outside investigators they hire, and, of course, administrators and office managers and all the coffee and, yes, booze, they have to wrangle. Rosters occasionally number in the hundreds for a single case, everyone bringing their super-specialized big brains—and bottles of vodka—to the conference table.

Ironically, this makes Community's Jeff Winger the most accurate lawyer Hollywood ever gave us: he specialized in misdemeanor criminal law, had a partner he always worked with, has a drinking problem, and when tasked with teaching the law more generally, had literally no idea because he'd always had paralegals to worry about it before. Truly, he's a hero for us all.

Psychiatrists And Psychologists Are Two Different Things (and Neither One Is Your Close, Personal BFF)

From the moment Tony Soprano first sat down in Dr. Melfi's office, Hollywood began a long, slow course correction of the mental health stigmas they'd helped propagate over the years. 20 later, portrayals of therapists have made some significant strides in the right direction—but there are still some things they just can't seem to get right. Two very obvious things, actually.

For starters, psychiatry and psychology are two distinctly different professions. But TV and movie characters only ever see one therapist, a doctor who does both weekly psychotherapy and prescribes antidepressants. By and large, that's not how it works in the real world and hasn't been for decades now.

Paramount Domestic Television

In the most general terms, psychiatrists deal with medications, while psychologists are the ones who do the talky-talk. While there are certainly some arguments for a psychiatrist also being a patient's therapist, it's actually incredibly and increasingly rare. According to a 2005 study, only 11% of psychiatrists still provided routine talk therapy—a number that has most likely fallen even more in the years since. In fact, earlier this year, The New York Times, reporting on the increase in mental health problems caused by the pandemic, pretty much took the separation as fact.

But let's assume that our fictional protagonists are seeing one of the two doctors who still shrink heads and write scrips. Fine. Here's part two of Hollywood's inability to understand the occupation: neither your psychiatrist nor your psychologist is your friend. In fact, the American Psychological Association Code of Conduct advises against it. While mental health professionals do have more wiggle room than other doctors when it comes to making sure the patient gets the help they need, boundaries still need to be set and respected. In fact, refusing to honor boundaries is not only unhelpful but often outright harmful.

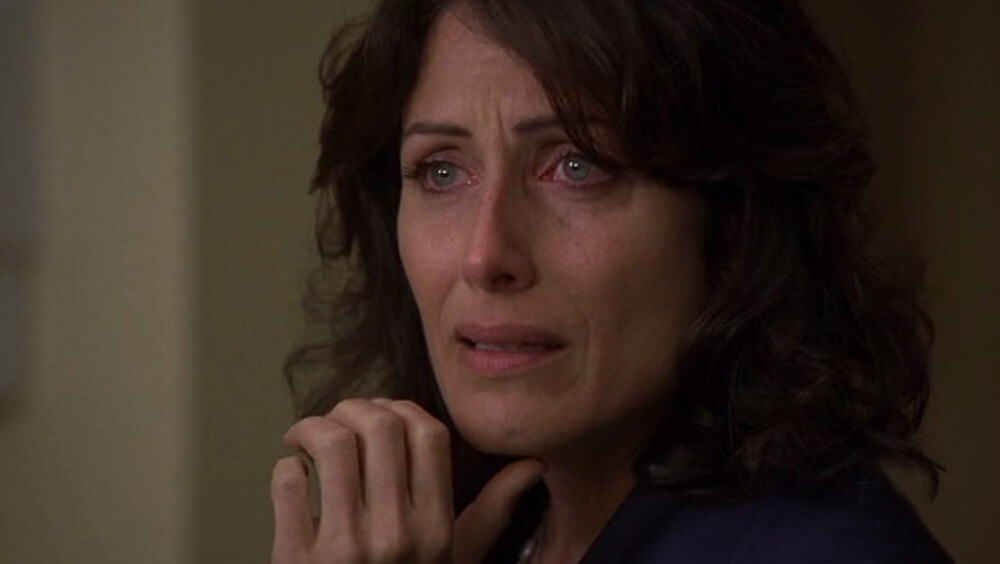

HBO

All of which is to say that therapists will rarely be on-call to hear your problems at any random moment—they're professionals, after all, with office hours and other clients. They also don't have to put up with your hilariously abusive garbage. Patients who routinely threaten, stalk, rob, or don't show up for years at a time can and arguably should be handed off to someone else, if not dropped entirely.

And yet, many on-screen therapists otherwise lauded for their authenticity still break boundaries like there's a prize inside. In Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, Dr. Akopian shrugs off Rebecca's breaking and entering and attempted theft while also getting too invested in her personal life. Justina Jordan on You're The Worst puts up with an onslaught of insults and physical threats and then gets stalked by Gretchen to boot. Even Dr. Melfi was way too involved in Tony's life, first by being targeted by his mob buddies and then seriously considering having him commit murder for her.

Sure, this is all better than outright vilifying psychiatrists, but swinging too far in the other direction isn't helpful to patient expectations of real-life therapists either.

Nurses Do So, So Much More Than They're Given Credit For

Ask a nurse what their favorite medical drama is, and you'll probably only get a growl in response. That is, of course, assuming said nurse can even find the 30 seconds to talk to you, Stranger Walking Through a Hospital and Asking Weird Questions. Because, you see, contrary to what Grey's Anatomy, House, New Amsterdam, and pretty much every movie about an inspiring doctor ever might tell you, it's nurses and technicians doing almost all of the actual work in a hospital on any given day.

Let's begin with the fact that nurses spend significantly more time with patients than doctors. Nurses are the ones at bedsides and, as COVID statistics unfortunately support, on the frontlines, most at risk of infection and angry outbursts. Doctors, meanwhile, aren't even necessarily in the hospital: they're running clinics or teaching classes or in their offices, spending literally half of their day doing paperwork.

ABC Signature

As a result, nurses are also the ones who act as patient advocates, checking in with their wards repeatedly and making sure they get what they need. Most patients see their doctor for two minutes during morning rounds, and that's it. Hell, at least part of a nurse's day is spent trying to find that doctor again, paging them over and over, for a crisis or prescription approval or what-have-you.

In fact, in real life, all those MDs, far from valiantly promising to make things better for the mysteriously-afflicted patient-of-the-week, are shown to actually lose empathy before they're even out of med school. If they can't figure something out or if an illness is proving more difficult to suppress than they'd care for, doctors have been known to get angry at the patient. For being sick.

Universal Television

Also, all that other stuff TV shows show doctors doctoring? That's not actually their job. Administering medications and chemotherapy, running tests, moving patients' beds, and drawing blood are all nurses' duties—or a technician's, or a respiratory therapist's, or transpo's. And that's before you get to all the high-tech machinery.

Believe it or not, Scrubs is routinely singled out as one of the best shows at representing nurse-dom on television. From their actual existence and storylines to the friction that comes from experienced nurses knowing more than residents to Carla Espinosa always being exhausted and overworked. The show best known for unleashing Zach Braff on the world is one of the only ones that doesn't make nurses want to throw their Crocs through the screen.

ABC Signature

And, to be clear, this isn't to say that doctors don't do anything—as much as you don't want a surgeon running your CT scan, you definitely don't want a phlebotomist diagnosing your appendicitis—but Hollywood seems to think they do everything, including the jobs of nurses and techs. Which, honestly, is just rude.

Eirik Gumeny is the author of the Exponential Apocalypse series, a five-book saga of slacker superheroes, fart jokes, and assorted B-movie monsters, and he recently added werewolves and assassins to The Great Gatsby. He’s on Twitter a bunch, too.

Tom Image: HBO, ABC Signature, Universal Television