5 Terrifying Experiments (That Raise Even More Terrifying Questions)

Mad science is undeservedly vilified. Yes, Frankenstein’s monster was an affront to all that’s good and wholesome, and an absolute abomination who left a gruesome trail of death and terror in its wake. But the resultant research paper that Victor Frankenstein probably wrote on galvanism and voltaic resurrection must have been lit. Likewise, the following unhallowed experiments encourage us to ask intrinsically essential questions—not just about science but about ourselves.

Eyecam

The internet-connected web camera, or webcam if you will, is a marvelous invention. It lets us enjoy a face-to-face with grandma back home, see lil’ Boots, and gauge grandma’s slipping mental faculties when lil’ Boots is mysteriously swapped for the entirely different cat owned by the family next door.

Don't Miss

But webcam design is impersonal and unfeeling, detracting from the poignancy of the conversation. So tech designer Marc Teyssier created the Eyecam, an anthropomorphic version that quietly (other than the screaming in your mind) reminds us to be more human:

Teyssier has practical goals; creeping people out was just a bonus. First, he wants us to be cognizant of all the hidden and not-so-hidden cameras and recording devices all around us. Be we in public or in our own gadget-filled, Wi-Fi-enabled homes, we’re always within range of peeping and prying electronic eyes and sensors. But the Eyecam doesn’t violate our consent because it forcefully lets us know we’re being watched.

Second, Teyssier wanted to endow this humble technology with human expressiveness. Eye contact and expressions are vital for communicating, displaying emotions, and fostering interpersonal connections. That’s why Eyecam has six servomotors to mimic physiological responses, both conscious and unconscious. It blinks, winks, and looks around while its brows and lids contort accordingly. It also responds to stimuli (i.e., the disgusted faces looking at it).

And good news, if you’d like one of these horrible things to reside in your own home where you live and sleep, you can build your own. In fact, Teyssier encourages you to do so, making the hardware and software both open-source.

Finally, as you gaze into your Eyecam, ponder the future of surveillance and anthropomorphic technology. Is it ethical, legal, and conscionable for spy devices to fill our world? Additionally, are there any merits to making technologies, in general, more human-like? We say: No. Absolutely none.

The “Selfmade” Project

Bacteria inspire disgust and detestation, but these microscopic critters keep us healthy and give us some of our favorite foods. So in an attempt to improve anthro-bacterio relationships, Open Cell bio-lab made cheese using bacteria harvested from human beings.

The cheese-making site was one of Open Cells’ 70 converted shipping containers near a west London market, which looks more like a murder scene from one of England’s endless cookie-cutter crime dramas than it does a place of experimental science. It’s here that the Open Cell team forsook God and made the world’s most blasphemous cheeses: a comté, a Cheshire cheese, a mozzarella, a stilton, and a cheddar. But instead of a traditional starter culture, they used bacteria from the armpits, face, nose, bellybutton, or toes of five British “celebrities” (the term is used very loosely), including chefs and musicians.

But this cheese isn’t made for eating, it’s made for thinking. And reflecting. And appreciating the microbes that are ubiquitous in our foods, environment, and ourselves. As part of the human microbiome, they influence our health, appetite, mood, and more.

They also make some of our favorite mouth-things, including (obviously) cheese but also chocolate, bread, miso, tea, coffee, and the ambrosia that makes our extended family members tolerable: beer. So next time you catch a whiff of stinky feet or unwashed armpit, consider that these odors are caused by the same Brevibacterium linens and Microbacterium lactium that make our cheeses creamy and our yogurts tangy.

The Nightmare Machine

MIT created the Nightmare Machine around Halloween 2016, as a proof-of-concept to explore a question that didn’t need exploring: can machines learn to scare us?

The answer turned out to be a resounding yes. Seriously, this stuff is very upsetting, goddamn great job, guys.

The Nightmare Machine is an artificial intelligence designed solely to terrify. Through the use of horrible, haunted algorithms, MIT’s mad machine turns regular photos into horror shows. It utilizes two deep learning methods. One extracts art styles from selected pictures and adds them to other images. The other generates imagined faces based on data (like zombie faces) fed into it. And as users ranked the scary pictures, the Nightmare Machine became “hungrier for more user data,” gorging itself disgustingly until it was able to “think and feel on its own.”

Its deranged virtual mind learned what scares us good, then augmented innocent photographs into eldritch horrors, transmogrifying regular faces into something glimpsed on picture day in hell.

And it’s not just faces but places. After being digitally spoon-fed images of haunted houses, ghost towns, and “toxic cities,” the Nightmare Machine transformed globally famous locales into cursed versions from alternate dimensions. You can even see a step-by-step of the insane algorithm’s “thought” process as it taints these once-proud landmarks, like this “slaughterhousing” of the Taj Mahal:

Or watch the Nightmare Machine turn the Louvre into a molten inferno. Remember here that machine is creating the image without any human guidance on which direction to go.

"Fear gives me pleasure; that is how I was programmed."

It can also create other effects, like a haunted house, ghost town, alien invasion, or that aforementioned toxic city theme applied to Capitol Hill. The real question though is why the scientists thought they were morally justified in hooking the nightmare machine directly to the brains of comatose patients, to trap them in an endless world of terror. To be fair, we have no evidence that they've done that, but we have our suspicions.

Organoids

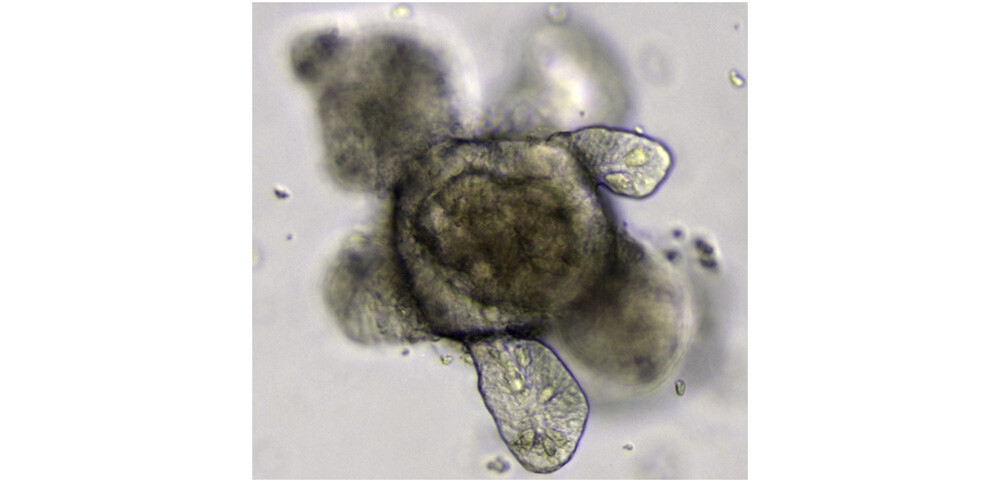

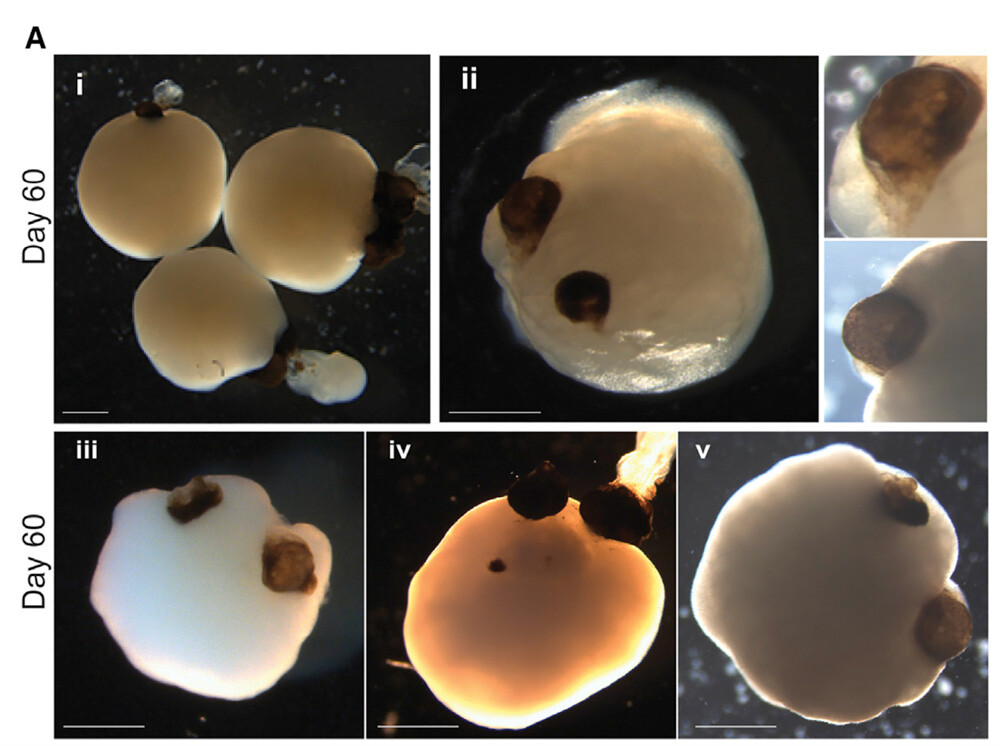

A lab with beakers full of quivering little organs, bubbling in foul-colored liquids, is a staple of mad science settings. But in real life, these little lab-made organs are becoming a legit scientific tool. These “organoids” are small, amorphous blobs of specialized organ tissue and highly gross and creepy:

They aren’t as sophisticated as real organs (yet), but they’re incredibly handy for allowing scientists to study how the real things develop, function, interact, and deal with disease. To that end, researchers really outdid themselves recently, both in terms of complexity and creepiness.

Previously, only single organoids were manufactured. But German scientists developed a twofer, cultivating a teeny-tiny brain that sprouted a pair of primordial eyes. And no, it isn’t as disgustful as it sounds. It’s worse:

If you want to grow your own mini-brain at home (it’s fun for the whole family), here’s how it’s done: first, take some stem cells and subject them to the same chemicals that cause the development of specific embryonic tissues. Then, add some vitamin A. Voila, two symmetrical eye-like structures should sprout. These prepubescent retinas also feature other types of ocular cells, including those of the lens and cornea. Intriguingly, they respond to light and even swap signals with their mini-brains, communicating like real organs would.

In the future, stem cell-derived/organoid-derived treatments could offer new retinas for the blind, or transplantable organs. Plus, researchers will be able to test treatments and substances on these lab-grown mini-organs (potentially made from a patient’s own tissues) instead of live-testing on mice and eliminated American Idol contestants.

“Graham”

The human body is pretty hardy, capable of withstanding all sorts of illnesses, injuries, and insults. But modern technologies, like cars, bring modern risks. And even the beefiest of our species is no match for thousands of pounds of crunching steel. But Graham is:

To remind us of our squishy vulnerability, and entice us to not be such dicks behind the wheel, the Transport Accident Commission of Victoria (Australia) collaborated with traffic researchers, a trauma surgeon, and an artist to create Graham: the man evolved to survive automobile accidents.

A wonky, alternate evolutionary line saw fit to equip Graham with multiple protective features. His awful skull is larger, more robust, and full of crumple zones that act like a helmet, which is purposefully designed to break on impact so the force doesn’t transfer to the brain.

His voluminous cranium also holds more cerebrospinal fluid, the brain’s natural shock-absorber. To safeguard his visage, Graham’s face is flat as a pug’s and offset by protruding, fat-filled jowls for extra cushion. And to avoid neck and head injuries caused by whiplash, Graham simply doesn’t have a neck. Instead, his ribs extend upward to his head to form a bony brace.

His vomit-inducing barrel-chest, with its descending rows of dog nipples, is adapted to resist impacts. So it’s full of airbag-like sacs between each rib to protect his vital parts and reduce his forward momentum. The dog nipples are aesthetic.

Also, to avoid spending his twilight years in a Rascal scooter, Graham has multi-directional joints and extra tendons throughout his lower limbs, along with “strong, hoof-like legs” so he can spring to safety like the kangaroos that so often find themselves embedded in the grills of Australia’s road trains. Finally, Graham’s tough, thick skin protects him from road rash, should he be sent ragdolling like a GTA prostitute.

Again, the project's goal is to remind us that we ourselves are not Graham, so when we drive, we need to keep in mind just how fragile we really are. But why can't we be Graham? C'mon—a few stem cells plopped in the right place, an enhanced endoskeleton made of servomotors, an army of bacteria to give our extra body parts a second brain, and we can bring this nightmare machine to life.

Top image: Transport Accident Commission