5 Spooky Skeletal Discoveries That Reveal The Terrifying Past

This Halloween, as you hang up your plastic skeletons (measuring either 6 inches tall or 6 yards, depending on your ambition), keep in mind that real skeletons aren't scary. The undead are scary, but real skeletons are just signs of the past. When archaeologists dig up skeletons, they're just educating us all, and there's nothing to fear.

Except for cases like the following. Because sometimes, the tomb raiders dig too deep, learn too much, and then must flee the site, screaming.

Peru's Skulls, Full Of Holes

Don't Miss

The ancient world had plenty of combat, of both the hand-to-hand and club-to-face variety. For those that survived, first aid was potentially more torturous than the injury. Especially in Peru, where the treatment for a skull injury was … an even gnarlier skull injury:

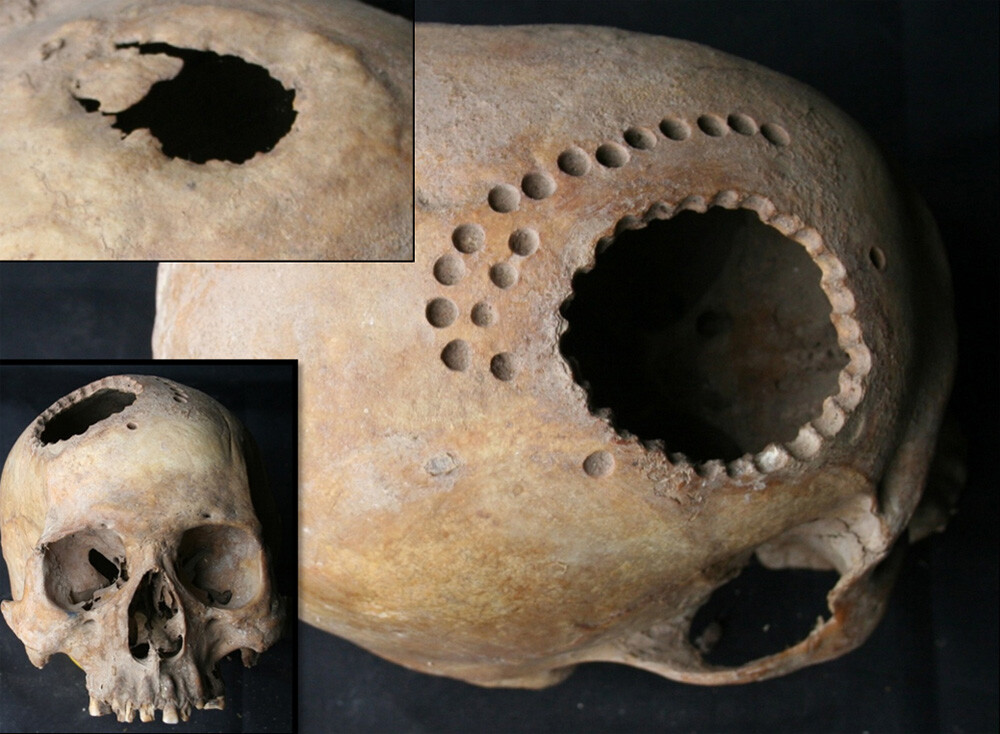

Peru’s millennia-old assortment of dented, chipped, and cracked craniums suggest people got clubbed and slingshotted all the time, making the region a "natural laboratory" for treating head trauma. Accordingly, archaeologists have discovered more than 800 ancient Peruvian skulls with evidence of trepanation, or therapeutic skull-drilling, dating to around 400 BC. If that figure sounds high, then you sure know your pre-Columbian craniotomy, because it is—these recently found Peruvian skulls outnumber all other examples of prehistoric trepanation combined.

Trepanation didn't start out great. The first patients only enjoyed a 40% survival rate. Though, that's still decent considering a 2,400-year-old shaman (did they award medical diplomas then?) just jack-o-lanterned your cranium.

Patient outcomes improved dramatically over the following millennia, and by AD 1000-1400, the survival rate increased to about 80%, with one sample population breaching the 90% mark. The Inca actually became such skilled skull-holers, their survival rate leapfrogged over that of the much-later Civil War surgeons, whose craniotomies killed about 50% of their patients.

One major factor (other than, you know, guns and explosions) was sanitation. War makes for unsanitary conditions: Surgeons literally jammed their still-damp-from-the-outhouse fingers into soldiers' gaping head wounds and manually removed shrapnel and busted blood clots. As a result, rampant infection rates claimed many lives.

Yet many centuries prior, the Inca healers prevented infections, unlike the more technologically advanced Civil War doctor-butchers. How? Uh, we're not totally clear on that, but it seems like they must have. Given the high number of skull surgeries (some of which featured many holes drilled at different times), it's possible trepanation was used to treat headaches or other such complaints. It's also likely some kind of anesthetic was used, be it straight coca leaves or a fermented beverage. So, seeing your doctor for a headache and ending up with an opioid addiction is apparently not a modern problem.

Gruesome, Gruesome Violence In The Desert

Modern landowners settle property line disputes with a game of cornhole, a fistfight, and a Budweiser, not always in that order. But 3,000 years ago, the first horticulturists in the Atacama Desert settled their donnybrooks the old-timey gentlemanly way: with fatal cranial trauma.

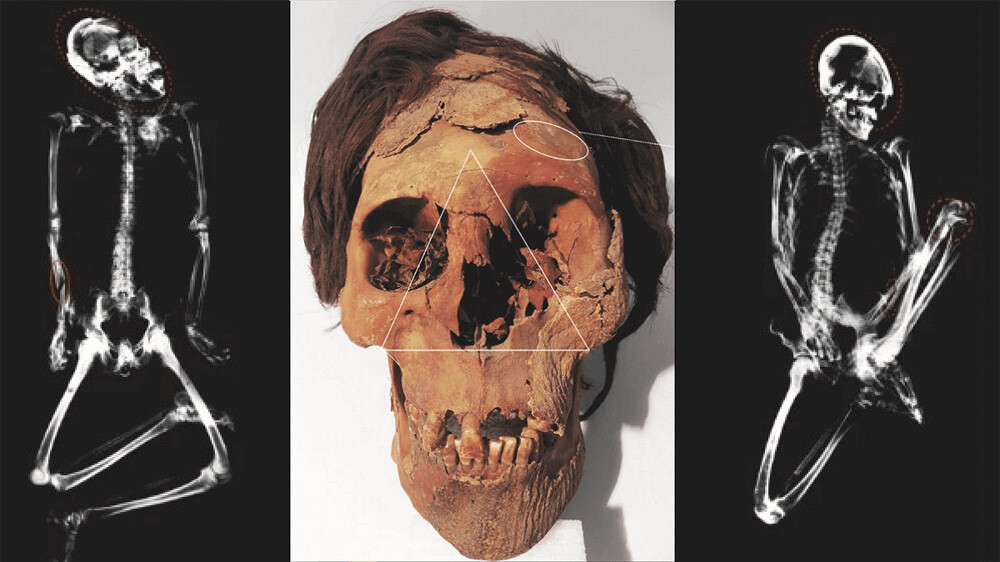

Researchers found these massively maimed specimens in Chile’s Azapa Valley, where they uncovered 194 bodies dating from the proliferation of Atacaman agriculture, around 1000 BC. More than 20% of the dead displayed disturbing disfigurements, such as "massive destruction of the face," or an "outflow of brain mass."

Overall, there’s an impressive variety of wounds, caused by knives, maces, sticks, spears, slings, arrows, fists, and hunting weapons. And there was no honor here, people were getting stabbed in the spine, lungs, and groin. Sadism also ran wild: A man's toes were apparently intentionally severed, while one woman's mouth had been pulled up across her face:

When researchers tested the creepily well-preserved bodies, some still sporting a healthy head of hair, they found mostly locals. These were neighborly fights between colonizing farmers and fishermen from the coast, spurred by territorial disputes and rising social inequality. The arid Atacaman environment allowed very little habitability, with basically two strips of productive land: a small, arable valley and a narrow coastline.

The climate didn't help, as marine resources grew scarcer and upped the pressure to produce farmed goods. And with a surging, hungry population, culture clashes, and potential political power struggles, the ancient Atacaman agrarians thought it natural to pummel each other over the rare bits of fertile real estate.

Plague Victims Waited For Death At Dargavs

When you first notice the quaint little buildings overlooking the Russian village of Dargavs, you might think you've stumbled upon a lovely North Ossetian mountain hamlet.

But you won't find any artisanal farm-fresh cheeses and clover honey here, only the moldering, centuries-old bones of plague victims. Which is a real bummer if you had your heart set on artisanal farm-fresh cheeses and clover honey. But these structures, growing ever more eerie as you approach, reveal themselves as family crypts, dating back to the 16th century or possibly earlier. It's uncommon to see above-ground burial sites in the region, and the spookiest of local legends tells that the necropolis was built because the badass cursed ground rejected the bodies inhumed here.

And so, entire familial lines, with their clothes and belongings, were interred inside their hereditary tombs, with 10,000 bodies in all now resting among the 99 stone monuments in this "little city of the dead."

Later on, the buildings became a quarantine for families as a few rounds of plague epidemics swept through the region in the 17th and 18th centuries. Old-timey folks here were more conscientious when it came to pandemics, sequestering themselves in these death-soaked structures with supplies of food and water. The wealthy built nice quarantine pens, while the poor huddled among the dead. All waited to either get better or die.

And, as you can see, lots died, bolstering the jumble of bones built up over many generations. Other tombs are slightly neater, with boat-shaped coffins to ferry the dead across a mystical river and into the afterlife. A few bodies are so well preserved that scraps of flesh still cling to their bones.

How delightfully creepy. Yet still, a disappointment if you were hankering for artisanal farm-fresh cheeses and clover honey after a nice hike.

King Tut's Mummified Kids

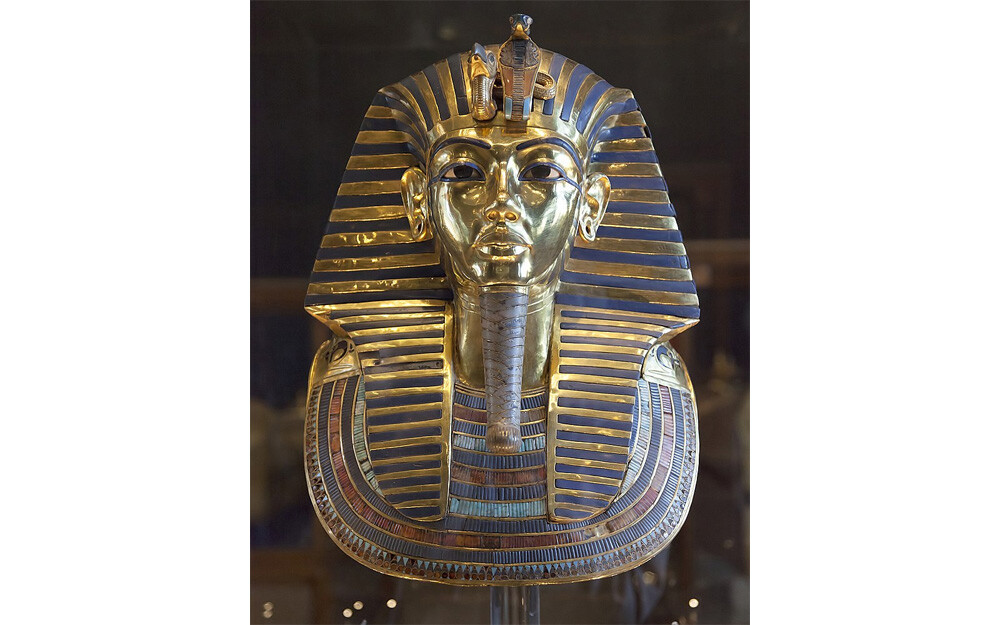

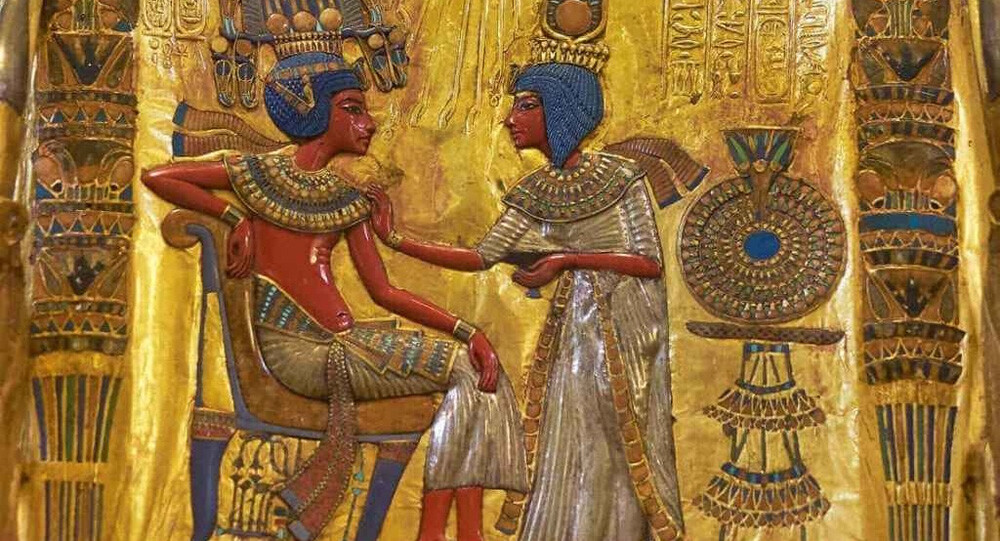

Ancient childbirth was too often tragic, as is apparent by the freakiest, most criminally underrepresented King Tut find of all time: an undecorated wooden box simply and underwhelmingly labeled item no. 317.

It contained two tiny coffins covered with black resin and decorated with golden bands, as per tradition. Inside were two smaller, nesting doll-style coffins, ornamented with gold foil. Typically, hot-shot mummies (and family members) get a nametag-like cartouche, announcing their appellation, but the inscriptions here only read "the Osiris," aka the god of the dead.

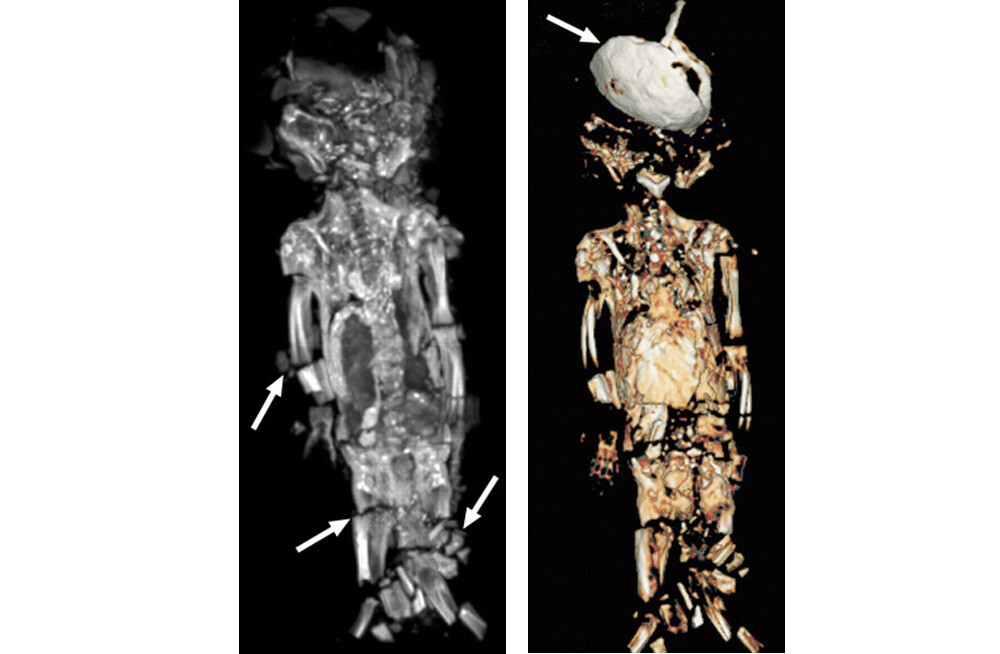

Inside the inner coffins were two minuscule mummies "317a" and "317b," which, spoiler warning, are creepy as all hell:

Genetic testing has found these to be the fetal, stillborn daughters of King Tut. 317a was about 10 inches long and born prematurely, with a gestational age of just under 25 weeks, according to calculations based on, among other factors, the length of certain bones. It has a tiny piece of umbilical cord remaining, its eyes are ever-so-slightly open, and its brittle, gray, translucent skin reveals the small bones within. It also appears naturally (or supernaturally) mummified, as there’s no sign of an incision.

Big sis 317b was larger, about 14 inches in length, with a gestational age of about 37 weeks. She received an artificial mummification and is a bit more nightmare-worthy, with tiny bits of downy hair on her head. It's believed King Tut fathered these children with his wife Ankhesenamun, who, fun fact, was also his half-sister, because you know the pharaohs liked to get freak-ay. Also, this possibly explains the gimpiness and premature death of his daughters.

There's Just Something About Decapitation

For an advanced, pioneering Classical civilization, the Romans sure were exceptionally brutal to all people who weren't Roman, and also to most people who were Roman. One time-tested favorite for laying down the law was good old fashioned decapitation, which Rome liberally utilized to subdue its subjects and slaves.

A Roman military supply farm in Somersham, England, might not seem like the obvious place to unearth a treasure trove of third-century decapitations, but the Romans didn't play around. Researchers at Knobb's farm revealed 52 burials, with 17 decapitated bodies among them, spread across three on-site cemeteries—see the brutality? How many farms do you know with three cemeteries full of headless bodies?

That's 33%, an "exceptionally high" number of beheadings even for such a slaughter-savvy empire, as the average headlessness rate in British Roman burials is a piddly 2.3-3.7%. These guys were really making their compatriots look like underachievers.

And it's not like the deceased died during a daring Spartacus-style slave revolt; they were separated from their heads while kneeling, execution-style, with a sword. Moreover, some of the bodies show shockingly poor Roman sportsmanship, revealing signs of torture, such as an older woman who was mutilated immediately before or after being executed.

The decapitees faced some unfortunate luck, as they caught the Romans on a bad century. The empire was facing increasing instability, and the brutal capital punishments increased, doubling in the third century and quadrupling in the fourth. Maybe the victims could take consolation in knowing that Rome would soon fall. Or in knowing that, many years later, millions of birds come poop all over Rome every single autumn.

Top image: Cambridge Archaeological Unit