5 Of The Most Badass Ways Cultures Used To Treat Their Dead

Death isn’t what it used to be. It still sucks as much as it ever did, but funerary traditions are generally way less dignified and extravagant than they were in past eras. Maybe it’s because McFunerals have become big business. Or maybe it's because we have too many other forms of entertainment to devote ourselves to nowadays.

Either way, the following ancient practices highlight the golden age of death. It's too bad you don't get to live anymore, but dying can still be a stylish, luxurious affair.

Chinese Jade Burial Suits

Don't Miss

One major way we’ve regressed historically is dressing the dead. Nowadays, we’re content to send peepaw to the afterlife in a JCPenney’s three-piece. But around 2,000 years ago, the Chinese sent their big shots to the reaper in sophisticated suits made of thousands of painstakingly crafted, linked-up pieces of jade.

The materials and construct were commensurate with status, and the most prominent muckety-mucks, like the emperors, had suits joined together with gold thread. The next level of nobility, your dukes and marquises and whatnots, usually received silver thread, while their children got copper thread. Those still further down the pecking order, yet significantly above the common classes, had to settle for silk thread. And the regular people, of course, were forbidden from enjoying jade-based burials and were probably lucky to get tossed into a ditch.

These suits were supposedly a thing of myth and apocryphy until archaeologists discovered two of them in 1968, belonging to Liu Sheng and his wife, Dou Wan. Since then, 20 more have been found. They required a mind-boggling amount of work and craftsmanship. The jade burial suit of Prince Liu Sheng of Zhongshan, a feudal ruler and purported womanizer, includes almost 2,500 finely hewn pieces of jade, held together by two-and-a-half pounds of gold wire. It’s estimated that such a suit would require ten years of work.

The dressing process also necessitated a number of jade plugs, which sealed the deceased’s nine orifices. Given what we know of royal court etiquette, we can only imaging the foul punishment exacted upon attendants for mishandling at the emperor’s jade ass plug, which was worth more than a commoner could earn in several lifetimes. Alternatively, not being generous enough with the royal codpiece could also presumably get you decapitated.

This tradition ceased at the end of the Han Dynasty, in AD 220, possibly because the royals feared tomb raiders would steal their fancy garms.

Greek Professional Mourners, Whose Ceremony Lasts Years

Modern funerals are a real snoozefest. You sit around for hours, enduring various “I’m so sorries,” and your only reward is some stale finger foods with the mild aroma of embalming chemicals. But a small band of women in Greece maintains an ancient funerary ritual that exudes all the drama and emotion associated with the culture that perfected the public tragedy. The women are known as moirologists (roughly translated as fate speakers or singers), and they mourn at funerals.

A few different cultures have their own tradition of professional mourners. The Greek ones dress in all black like a Johnny Cash tribute band and wail “fate songs,” or improvisations about the deceased’s life, lauding their accomplishments and probably skimming over indiscretions.

It’s a practice inspired by the soulful dirges sung by choirs in ancient Greek tragedies and also an even older tradition dating back to the eighth century BC. Mourning relatives improvised lamentations and tore their hair out (potentially explaining Greece’s high balding rate) as the bodies of their loved ones lay in the household.

The moirologists symbolically wash the body with wine or vinegar, clothe it in church garments, and sometimes place a coin on its forehead or between its teeth to fund the deceased’s journey across the River Styx, because annoying service charges are thousands of years old. Then, the lamentful moirologia, or fate singing, must continue unbroken until sundown, as an interruption can doom the souls of the departed and all those in attendance. As the sun sets, the women remain quiet until the following day—a tough ask for a gossip-prone culture.

Offerings and jeremiads are continued on specific dates over the following three years, while the deceased’s family is still mournfully attached to the body. This period concludes after three years: the family is released from their sorrowful bondage and the departed is inducted into the afterlife, as the body is exhumed from the cemetery and placed in a local ossuary or a mausoleum. Wow, that sounds like a whole lot for the family to have to suffer through. Suddenly, "sorry for your loss" and formaldehyde sandwiches doesn't sound so bad.

Middle Eastern Skull Plastering

In modern times, we honor our forebears by putting up a few pictures and getting a bit drunker than average on their birth-and-death days. But almost 10,000 years ago, when civilization was just getting started, the dead literally remained with you forever because you buried them beneath your house.

Which we’re pretty sure is illegal today? At least it would drastically lower the resale value if the new owners knew they’d be playing Parcheesi above some decaying old patriarch’s syphilitic bones. But it gets worse, according to some Middle Eastern skulls that highlight a tradition that would get you institutionalized today:

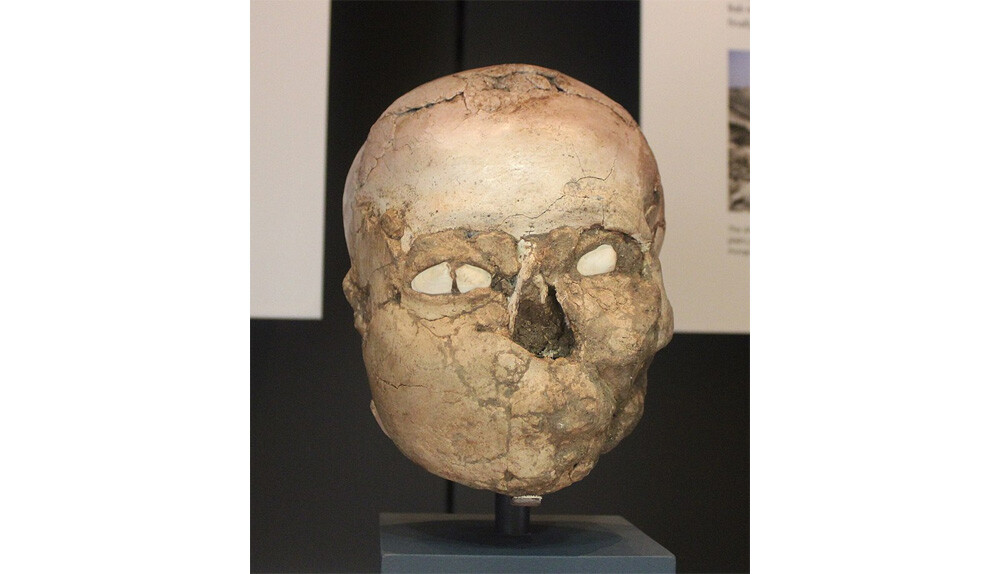

Once the flesh of the corpse rotted away, their skulls would be dug up, plastered, painted, and decorated with seashells for eyes. This plastered head was then kept on a mantel or wherever to provide a constant reminder of your loved one.

Sure it looks creepy now, but imagine it when it was freshly decorated, with its painted features and mustache and potentially some fake hair—never mind, that sounds way worse.

The families of these individuals would have venerated them personally, then the skulls would have been passed down until their origin was forgotten, like that turkey-shaped serving platter you own from who knows where. When the skulls’ identities were no longer known, archaeologists believe they would have been venerated as sacred objects for ancestor worship, and eventually reburied.

One of the best-studied specimens is the Jericho Skull, belonging to a man who lived 9,500 years ago. He died in his forties and had crappy, painfully infected teeth. And his alien-looking dome revealed he had his head tightly bound as an infant to change its shape permanently.

Just imagine: under that plaster, old as civilization itself, is the skull of a real man who really lived, a really long time ago. Wow. Too bad we’ll never know what he looked like.

Oh wait, thanks to the wonders of modern science, we can see exactly what he looked like. The recreation required micro-CT scans, 3D modeling, police forensic techniques, and layer-by-layer tissue structuring. As a result, this man’s face can be seen again for the first time in nearly 10,000 years:

Let this be a reminder to you. Live your life in a way that’ll have scientists in AD 12,000 recreating your face.

Medieval Japanese Monks Drowned Themselves In Coffins

For the world’s chillest belief system, Buddhists have the most brutal death rituals. Be it mummifying or burning themselves alive, feeding their corpses to vultures, or sealing themselves inside statues, this religion sure knows how to die.

It was no different at the historical Fudarakusan-ji in Japan, which is an unassuming-looking temple in Nachikatsuura:

To attain salvation and enlightenment, the elderly monks here undertook a sea-faring suicide mission known as Fudaraku Tōkai, or “crossing the sea to Fudaraku.” For more than a thousand years, these monks went searching for the mythical Fudaraku, or Mount Potalaka, thought to exist somewhere off the southern coast. This ageless paradise was said to sit atop a brutally inaccessible mountain peak and to house a bodhisattva (a deputy Buddha) named Avalokiteśvara.

So the sea-pilgrims, or tokaisha, set out in oarless boats that were functionally floating funerary shrines. The tokaisha were adorned with holy robes and sealed inside their scented-wood sea-tombs with a lantern and a month of food. And they joyfully drifted to their deaths as their compatriots looked on and sent their prayers.

Death occurred in various crappy ways. Sometimes the monks exited their floating coffins and jumped into the ocean. Other times, they pulled a plug in the bottom of their boats and went gurgling down with the ship. Occasionally, they’d sit there until they starved or died of thirst.

Once, when a monk changed his mind and tried swimming back, the crowd of onlooking pilgrims killed him by flinging stones at his head, which is understandable—they came for a Fudaraku Tōkai and they were going to get a Fudaraku Tōkai, goddamnit.

Roman Sarcophagi Were Impossibly Elaborate

If we gloss over all the genocide, slavery, and Epstein-esque sexual practices (as we do with most ancient civs), the Romans did lots of good. They developed the preferred language for demon summonings, built aqueducts and roads that were useful long after they died, and even created some incredible art as they died.

That’s a genuine Roman sarcophagus, an Imperial Roman innovation inspired by the Etruscans and Greeks. It didn’t come into use until late because during Rome’s Republican Period, circa the sixth century BC to the twilight of the first century BC, they cremated their dead and interred the ash-filled urns in family tombs.

But during the Imperial Period, which lasted from the close of the Republican Period until Rome’s capitulation in the late fifth century AD, they adopted this statelier, more extravagant burial tradition. High-class folks commissioned marble sarcophagi, ornamented with reliefs as rich in happenings as a Where’s Waldo? anthology, while non-elites had to settle for limestone, lead, or wood. Epic battles, like those between the Romans and Goths, are a popular theme and feature a mind-boggling level of detail:

Adhering to their obsession with all things Hellenistic, including the abuse of underaged house-slaves, the Romans often decorated their grand coffins with scenes from Greek myths:

Hunting scenes and images of heroes like Achilles boasted of the deceased’s bravery and taurine virility. Other symbolic gestures, like the gifting of a lyre, showed culture and intellect. Celebratory Dionysian depictions promised a wine-and-festivity-fueled afterlife; a bygone tradition, sadly, because how rad would it be to bury your gran-gran in a coffin decorated with scenes of keggers while "Party Rock Anthem" blares through the cemetery.

Top image: Typhon2222/Wiki Commons