4 Weirdest Ways That Animals Get It On

Generally, mating habits and reproductive strategies seem pretty uniform throughout the animal-and-human kingdom, at least on the surface. Penis goes in, and sometime later, babies come out. But it's what happens between those two events that leave a lot of room for evolutionary interpretation. And various species have developed strikingly different methods to ensure their genes are passed down.

These methods are sometimes devious, oftentimes disgusting, and occasionally seem downright impossible …

The Bird Evolved Specifically To Cock-Block

Don't Miss

Evolution usually happens little by little, but sometimes it happens by a little bit more. A mutation in a supergene, a chunk of chromosome containing about 100 genes, may allow multiple changes to take hold. And it endowed ruff birds with incredible sexual subterfuge: males that look like females to get laid.

Basic male ruffs, a type of wading sandpiper, are called territorials or independents. They're ostentatiously colored and patterned, so each looks unique. They also sport feathery head-tufts and (eponymously) extravagant neck plumage—they're called ruffs after the decorative collars old-timey people wore to draw attention from their oozing syphilitic sores:

To initiate mating, the territorials strut around the "lek," a large gathering of males and females, flashing their plumage and performing aggressive moves to entice females. And when enticed, the females crouch and display their cloaca. Pretty simple so far.

But two types of male "morphs" evolved to take advantage of males' hard work and females' inattentiveness. One type, satellite males, have neck plumage but drab white coloring. Their courtship displays are less aggressive and serve as "wingmen," making territorial males look better, which is why they haven't been pecked to extinction. Sometimes, satellites manage to sneak an opportunistic poke for themselves when they run across a crouching female.

The second morphs are called "faeders," and, like Square Enix charging $70 for a Final Fantasy VII "Remake" that's only a third (at best) complete, they evolved to cuck other males. Faeders comprise possibly less than 1% of the population and look like larger females, but with huge testicles. These female-mimicking faeders sneak around the lek, opportunistically mounting the real females bending over for their (on-rushing) males, who then confusedly slam into the back of the faeder, forming a "sandwich."

Faeders are such good female mimics that scientists only recently discovered them, despite their 3.8-million-year-long existence. Their ability to blend among females also keeps them safe from scuffles with rival males -- a la Bugs Bunny dressing up like a woman to fool Elmer Fudd.

Deer Mice/Beetle Sperm Team-Up (And Race)

Nature imbues great sophistication into its tiniest features. Even sperm cells are more capable than anyone imagined. Those of various rodent species, for example, band together like drafting NASCAR drivers or Tour de France riders forming a peloton to increase their speed.

Rodents' "brother sperm" recognize one another and form "trains." Dozens of cells latch onto one another via small hooks on their heads, forming a DNA-carrying conga line that swims 50% faster than any lone-wolf mouse sperm could on its own if you'll allow us the pleasure of mixing animal analogies.

Sperm-trains are especially effective for promiscuous species, like deer mice. By teaming up, sperm try to out-compete their rivals in a microscopic race that would be infinitely more captivating than either NASCAR or cycling if only someone could secure licensing rights. The sperm recognize themselves even when pitted against sperm from a sibling mouse, showing a high level of discrimination among the sperm and a low level of discrimination among the mice.

Oddly enough, or maybe not at all considering convergent evolution, diving beetles use a similar insemination method. Scientists knew bugs had insane sex organs. But the reproductive tract of diving beetles wasn't really studied until about 10 years ago because looking at beetle vaginas all day is a tough ask.

It turns out that diving beetles and TLC share a “No Scrubs” policy. And the former's reproductive tracts have evolved into tiny labyrinths to ensure that only the most potent sperm-givers knock her up. This female-driven sexual evolution kicked off a procreational arms race, with beetle sperm becoming more cunning in response. So the sperm cells latch onto each other to aid in navigation. And a single cell becomes a gigantic, writhing, worm-like aggregation of hundreds or thousands of members, with their haphazardly thrashing tails slowly pushing the jumbled mass toward the egg.

The lady beetles' excessively tortuous tracts may also be advantageous for another reason. Females sometimes have little choice in picking their mates, who may hold them underwater, pressuring them into mating by the threat of drowning.

But bugs are weird, and the biological shenanigans don't stop at insemination. A female may hold onto the sperm for a long time, years even, before self-fertilizing. The adaptation is as successful as it is gross, apparently, as there are now more than 4,000 species of predaceous diving beetles worldwide.

Narcisse Snake Orgies

The Narcisse Snake Dens of Manitoba, Canada, host one of nature's most awe-inspiring and repulsive wonders: the crazy springtime orgies of the world's largest concentration of snakes. Every year around May, tourists and wildlife aficionados marvel and lose a little of their lunch as 75,000 red-sided garter snakes explode from their winter dens or hibernacula (there's your word of the day). They only have one F on their mind, and it isn't food or fun.

These snakes hibernate for more than half the year, and when the males surface, they're too randy to eat and spend the next few weeks waiting for the females to appear. It's an insane example of intermittent fasting: guys go more than eight months without feeding, which is a fun fact to unholster next time a coworker complains about missing their daily McGriddle.

Once the females appear and release their estrogenic pheromones, they're instantly mobbed like it's some eastern European bride market. The resulting "mating balls" are frenzied masses that sometimes contain a hundred or more males dogpiling a single female.

Maybe that's not surprising, considering the male to female ratio here can be as high as 10,000 to 1.

After the male deposits his sperm via his double-penis, he also inserts a gelatinous plug that blocks other males' double-penises (fun facts numbers two and three) to secure his own sirehood. Following this epic orgy, 250,000 babies are born in the summer then mysteriously disappear from the dens by the fall. They're potentially hiding in anthills or, according to one scientist, freezing then coming back to life during the thaw like Brendan Fraser in Encino Man.

Should you be inspired to solve the mystery, the site houses four active snake dens dotted across a nearly two-mile-long trail. So you can get a bit of exercise while you watch dirty snake sex and consume 2,500 calories of M&Ms and sugared pecans under the guise of "trail mix."

Siphonophores Are A Colony Of Clones

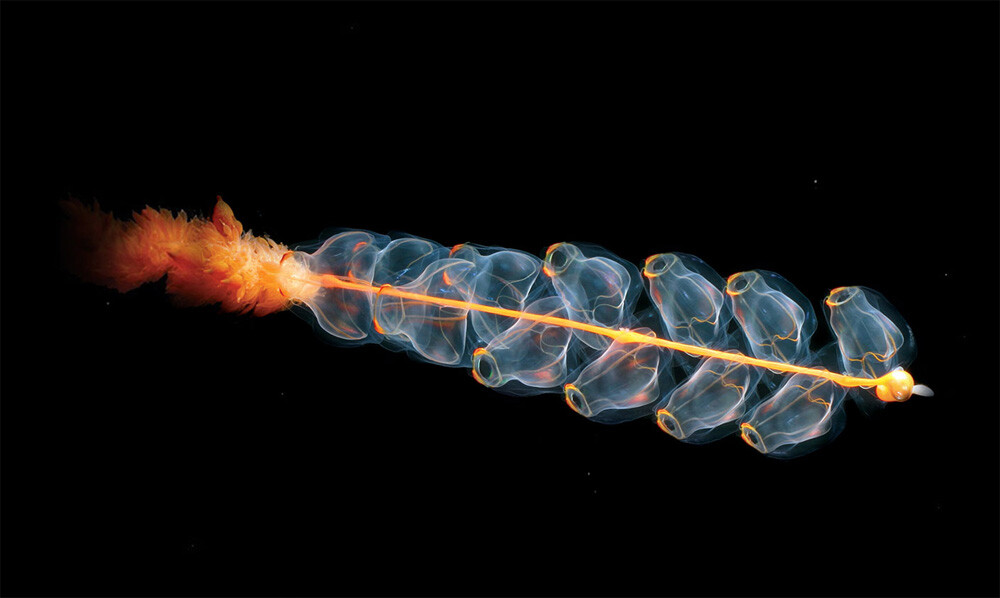

Mother Nature obviously tossed back a few Appletinis before creating siphonophores. These deep sea-dwelling invertebrates are possibly evolution's craziest bastards for multiple reasons. First off, they look like this:

Secondly, siphonophores are a single animal and also not a single animal. They're colonial creatures, made up of a colony of clones. But there's no central brain. And each clone has a nervous system and is basically an individual interconnected multicellular animal called a "zooid." But no single zooid could live on its own because they're all specialized to perform certain biological functions. The predatory dactylozooids form tentacular appendages used to capture smaller creatures. The carnivorous gastrozooids are specialized for feeding and have tiny stinging cells that stun prey.

Other clonal organisms create pneumatophores, the gas-filled equivalents of pool floaties that buoy a Portuguese man o' war (a siphonophore, not a jelly). Alternatively, some form swimming bells or bulbs called nectophores, which shoot jets of water to propel the siphonophore throughout the sea and into your nightmares.

"Nono, that's part of the animal."

And the so-called gonozooids are responsible for reproduction. Each "baby" siphonophore starts off as a single zooid, or bud, which self-replicates, skipping the sexual intercourse stage that so many other happily animals rely on.

This isn’t an animal, it’s a JRPG summon.

Overall, scientists have found nearly 200 types of siphonophores in an incredible variety of terrible-looking, otherworldly configurations. Some live more than 3,000 feet down and produce their own light via bioluminescence. Others grow well over 100 feet in length, longer than a blue whale, but remain as thin as a broomstick.

Considering they were first discovered by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, they must have absolutely blown the minds of a populace that still believed menstrual blood came from the Moon or whatever.

Top Image: Chris Friesen/Oregon State University