4 Forgotten Native American Protests That Should Be In History Books

Societal upheaval was a central theme of American history in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Anti-war protests, the Civil Rights Movement, women’s equality protests, and more highlighted the rapidly changing world. While they frequently receive less coverage for their contributions to this period, Native American rights movements were particularly active through the occupation of significant landmarks.

In the decades before the protest movements, U.S. Native American policy was built on termination doctrine. Laws in this era focused on fully assimilating Native Americans into American society by abolishing some tribes and relocating Natives into urban areas. This failed to achieve increased opportunity for indigenous peoples and was seen by many as an attempt to erase traditional cultural practices. Frustration over these policies led to protests, which helped spark the occupation movement ...

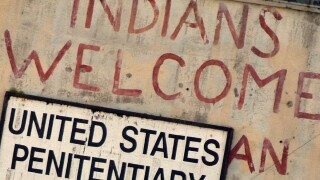

Occupation Of Alcatraz

Don't Miss

On November 20, 1968, a group of Native American protesters led by activists Richard Oakes, LaNada Means, and John Trudell broke through a Coast Guard blockade and began to occupy Alcatraz Island. They called themselves “Indians of All Tribes” (IOAT) and claimed that the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie between the U.S. and Sioux gave Natives the rights to federal land that was abandoned. Alcatraz was closed as a prison in 1963, and protesters believed the land should have been returned to Native American ownership.

The Occupation of Alcatraz quickly gained attention from Native Americans across the country as well as allies. Hundreds of protesters occupied the island, and they established services such as a school for native children and a clinic. The Coast Guard attempted to stop supply shipments from reaching the occupiers, but food and other supplies still found their way to Alcatraz. Financial support even came from major celebrities of the time. Creedence Clearwater Revival donated $15,000 for a boat to assist the protesters.

Occupation lasted for 19 months, but by the final months, things had taken several bad turns for the protesters. Crappy gentrification occurred as hippies and other non-Natives had moved to Alcatraz, which led to an increase in drug use. This also took away from the message the protesters wanted to demonstrate of Native self-determination. General hardships from the limited supplies also left some too demoralized to keep the protest going. The government cut utilities to the island, and a fire destroyed buildings. Finally, in June 1971, U.S. marshals and other federal agents removed the final protesters from Alcatraz.

While the Occupation of Alcatraz did not end in Native Americans gaining land rights, it did bring the issue of Native American rights to national attention. It also inspired similar occupation movements in the future.

Chicago Indian Village

As a result of the United States’ effort to move Native Americans into urban centers, Chicago had one of the largest concentrated Native populations in the country. This forced assimilation was unsuccessful at improving Native living conditions, though, as many found themselves in poverty, unable to find opportunities in the cities.

On May 6, 1970, a Native American woman named Carol Warrington was evicted from her Chicago apartment following a rent strike to protest the apartment’s conditions. Warrington’s story quickly gained attention among other Natives in the Chicago area, particularly from the Native American Committee (NAC), a Chicago-based group dedicated to improving education and living standards for indigenous people. Michael Chosa, an NAC leader, mobilized a protest against Warrington’s eviction. He set up a teepee near Warrington’s apartment and encouraged others to join. Warrington’s apartment was located near Wrigley Field, so the protesters were hard for Chicagoans to ignore.

While Chosa and a small number of protesters remained, most left after a few days. Their goal was to spread awareness about poverty and education inequality faced by Native Americans, and when they believed that the protest achieved this, they stopped.

The protesters who remained called their protest settlement the Chicago Indian Village. In time, they left the area near Wrigley Field and attempted to settle in a few different spaces near Chicago. However, they were never able to successfully make a statement or gain publicity as they did at the start of the occupation.

While the Chicago Indian Village did not lead to any policy change on its own, it helped spread awareness of the struggles Native Americans sought to highlight. This occupation occurred while the Occupation of Alcatraz was still ongoing, and each new act of protest helped keep attention on the overall subject.

Bureau Of Indian Affairs Occupation

Understanding the Native American rights movements of this era means becoming familiar with the American Indian Movement (AIM). This organization was formed in Minneapolis in 1968 and was a key player in many noteworthy protests. While they were not involved in the Occupation of Alcatraz, they did visit the Chicago Indian Village. However, AIM co-founder Clyde Bellecourt was unimpressed with the Chicago protest and did not seek further involvement. AIM would become crucial for the final two protest movements in this list, though.

In 1972, a nationwide Native American movement known as the Trail of Broken Treaties was organized by the AIM. This traveling protest sought to reacquire the right to negotiate treaties between Natives and the U.S government and to improve the overall conditions faced by Native Americans. The Trail ended on November 3, 1972, at the headquarters of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington D.C.

Hundreds of AIM protesters occupied the building. Once inside, the occupiers barricaded themselves in with the furniture available. Their goal was to get President Richard Nixon to approve their 20-point proposal, which would restore certain tribal rights to improve Native living conditions and relations with the United States government.

The building's occupation ended just a few days later but with more promise than the Occupation of Alcatraz or the Chicago Indian Village. During this time, members of Nixon’s staff were meeting with tribal leaders away from the Bureau of Indian Affairs building, and the 20 points in the AIM’s proposal were taken seriously. On December 22, 1973, Nixon signed the Menominee Restoration Act, which gave tribal status back to the Menominee of Wisconsin, a tribe that previously fell victim to the policy of tribal termination.

In a rare turn of events, this represented a time where it was unfortunate that Nixon resigned when he did. Because of the Watergate scandal, Nixon resigned in August of 1974, and the final months of his presidency were shrouded in the scandal and were unproductive as a result. While some tribes did regain their tribal status after the Menominee, the AIM’s goal of regaining treaty authority was not achieved.

Wounded Knee Occupation

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, home to the Oglala Lakota people, had been one of the poorest areas in the entire United States. In 1972, the situation for the Oglala got worse with the election of Richard Wilson as Oglala president.

Under Wilson, corruption was inescapable. He worked closely with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, much to the dismay of the Natives, and exercised extreme control over the use of tribal lands, favoring outsiders over Oglala. Wilson was known to intimidate and carry out his private militia, the Guardians of the Oglala Nation, which received BIA funding. This militia was so cartoonishly evil that their acronym was GOON.

The Oglala tribal council attempted to impeach Wilson, but he avoided trial. This, as well as frustration at the overall mistreatment that Natives in the region had faced, led members of the Oglala Tribe and activists from the AIM to occupy the reservation town of Wounded Knee on February 27, 1973. Wounded Knee already carried weight as the site of the infamous 1890 massacre, and the symbolic value of choosing this space for the protest was not lost on anyone.

For 71 days, roughly 200 Native American protesters occupied Wounded Knee and proclaimed themselves the Independent Oglala Nation. As with other occupations, the U.S. government surrounded Wounded Knee, as did Wilson’s GOONs. They set up roadblocks to limit travel to and from the occupation. This eventually turned into a full siege. Utilities to Wounded Knee were cut off, and so were supply lines. The FBI attempted to turn the public against the AIM through misinformation that claimed that hostages were held in Wounded Knee. This was ultimately unsuccessful, as the public generally took the Native American side during the occupation.

As the siege went on, there were incidents of shots being fired by both the government and protesters. On April 26, an occupier named Lawrence “Buddy” Lamont died after being shot by a sniper. This death marked the beginning of the conclusion, and the occupation was ended by other sides on May 8. Key AIM leaders were arrested for their role in the occupation, but their charges were dropped.

After the occupation, Richard Wilson continued to rule through violence and corruption. He won reelection in 1974 despite many claims of fraud, and some believe that his GOONs killed up to 60 political opponents.

Like other occupation movements on this list, the Wounded Knee Occupation did not grant Native Americans the rights that they wished for, but it did highlight the struggles they faced. This was a highly publicized movement, and without it, the average American likely would have never heard of what Wilson was doing or about the overall conditions faced by the Oglala.

Top Image: Loco Steve/Wiki Commons