5 Wondrous Ways People Used Science To Make Art

Art and science are not so dissimilar. Both require hard work, careful observation, and tireless dedication. And they both seek universal truths. The only difference is that scientists explore those truths with microscopes and telescopes, while artists explore them with peyote and unprotected sex.

And what do you get when you combine scientific tools, techniques, and knowledge with artistic creativity, freedom, and a propensity for mind-altering substances? Something real fine, that’s what ...

Microscopic Sandcastles

Don't Miss

Good art should inspire questions. Like what is true beauty? Is there a reason for our existence, or are we just the random, congealed atomic ejaculations of a meaningless universe? More importantly, how the heck could someone draw a castle on a grain of sand?

If you’re thinking they did it with a laser, you’re wrong. The laser beam was too big, so they used a focused ion beam scanning electron microscope, the thing used to see some of the smallest things in existence. The sandcastles were created by MIT Media Lab designer Marcelo Coelho and artist Vik Muniz, who spent four years crafting four incredibly minuscule sandcastles on sand grains less than a tenth of an inch across.

Preparing and selecting the suitable grains was just as tricky as the highfalutin’ beam technology used to etch it. The grains were first cleaned in methanol to remove oily imperfections, then acetone to clean off the methanol, and then sieved to separate those of the right size: under half a millimeter, or less than 0.04 inches.

About 50 to 150 of these grains were smattered on little metal stubs, which held them steady for inspection and etching. The stubs went into a focused ion beam scanning electron microscope (used to fix circuits on silicon chips), where Coelho searched for a flat, perfectly sized-and-shaped grain. A process wholly up to the gods’ caprices, which took “anywhere from ten minutes to ten hours.”

The machine then heated its inner clutch of gallium metal, vaporizing it and releasing its ions in an atomic Conga line of charged particles. As the beam smashed into the sand grain, it removed tiny amounts of material with each pass, making an ultra-fine, nigh-invisible etching.

The castles are so utterly minute that an electron scanner, at maximum resolution, needed to stitch together at least nine “snapshots” of each grain before producing a viable image. In total, Coelho and Muniz spent about 300 hours of lab time to create four images, presumably with an ever-growing line of angry, white-coated scientists waiting outside the door.

Anatomical Paper-Art

Artist Lisa Nilsson combines old-school paper quilling techniques with new-school medical science to create anatomical paper art that would captivate, amaze, and slightly gross out both time periods.

Nilsson, an illustrator who picked up the anatomical arts and earned a medical assistant certification in 2010, was inspired by the Medieval reliquaries that hold finger bones or other anatomical artifacts from long-dead saints, like the half-eaten grilled cheese of St. Jerome.

Reliquaries were sometimes decorated with paper quilling, devised by Renaissance-era nuns and monks who wanted to pimp out their hallowed objects on the cheap. So they took the gilt edges from disused bibles, coiled them around a quill, and used that in place of gilding with genuine gold filigree. Plus, arts and crafts provided a nice distraction from the constant praying, stale bread, and sexual repression. Quilling later became popular with laypeople looking for domestic décor and activity, including the young English ladies who previously sat on their fainting coaches clutching a medicinal vibrator all day.

More recently, Nilsson’s Tissue Series fabulously revived the art form, using gilded edges from old books and Japanese mulberry paper to display all the body systems that, barring a chainsaw accident, remain hidden in their cozy little cavities.

Nilsson utilized a variety of rolling techniques to replicate different tissues and the jumbled array of shapes and textures that give rise to the human machine. She even faithfully recreated the natural left-right asymmetries our bodies possess both internally and externally. And for anatomical accuracy, she consulted the Visible Human Project, which reveals all the inner intricacies of the human body through 3D imagery and cross-sections.

Nilsson also spends several days crafting a box enclosure for her works to bestow a “reverential and precious atmosphere,” creating something “between a reliquary and a scientific specimen.” It’s also a humbling reminder of the terrifying biological monsters that lurk beneath our skin:

Chlorophyll Prints

The mind of an artist is vastly different from that of the average everyday schmuck. Consider the creative thought process of photographer Binh Danh, who noticed that the sunlight-deprived grass beneath a hose became discolored and thought, “Hot damn, I can use that to make badass art!” Danh’s “chlorophyll printing process” takes advantage of photosynthesis and the honest, hard-working plants that break their backs every day to produce enough oxygen to power our fat bodies.

Making a “chlorophyll print” is a relatively simple, labor-non-intensive process. Danh selects a suitable leaf, often from his mother’s backyard, then prints a photographic negative on a transparent sheet and places it on the leaf. He sandwiches the two between a solid backing and a glass plate on top and leaves it to bake in the sunlight for a few days. As sunlight is blocked from reaching certain parts of the plant, those pigments lose their color, and an image is produced. Though the technique only works correctly about 20% of the time.

Danh’s works focus predominantly on war. Not in a political sense, but as a humanistic reminiscence to honor the many unremembered individuals and conflicts.

Danh's most personal and poignant project, Immortality, eternalizes the forgotten horrors and injustices of the Vietnam War, which he (as an infant) and his parents escaped when they immigrated to California in 1980. Since matter is never destroyed, only transformed, he says these portraits capture an “elemental transmigration: the decomposition and composition of matter into other forms.” The wartime scenes become part of nature, “living inside and outside” of the leaf, as the victims and remnants of the war have forever become part of the Vietnamese landscape.

Wow. All of a sudden, we’re a lot less proud of the handprint turkeys stuck to our fridge since the 5th grade.

Jovian Fractal Art

NASA’s 60-foot-wide, windmill-bladed Juno Spacecraft entered Jupiter’s orbit in July 2016 and has since been performing a gravitational Lindy Hop around the solar system’s biggest planet.

It swings a highly elliptical, 53-day orbit to avoid Jupiter’s insanely murderous radiation while its suite of instruments soak up the radiation data seeps from the gas giant like a sustained, slow-releasing cabbage fart. Its sensors and “-ometers” also allow Juno to peer through the obscuring clouds, like a pervert peeking through the slats of a dressing room door. And, like a dressing room pervert, Juno is equipped with a good-old-fashioned visible light camera, JunoCam.

NASA gladly releases all JunoCam images (except those of the orbiting alien base) for public enjoyment and even encourages people to get creative with photo-editing processes.

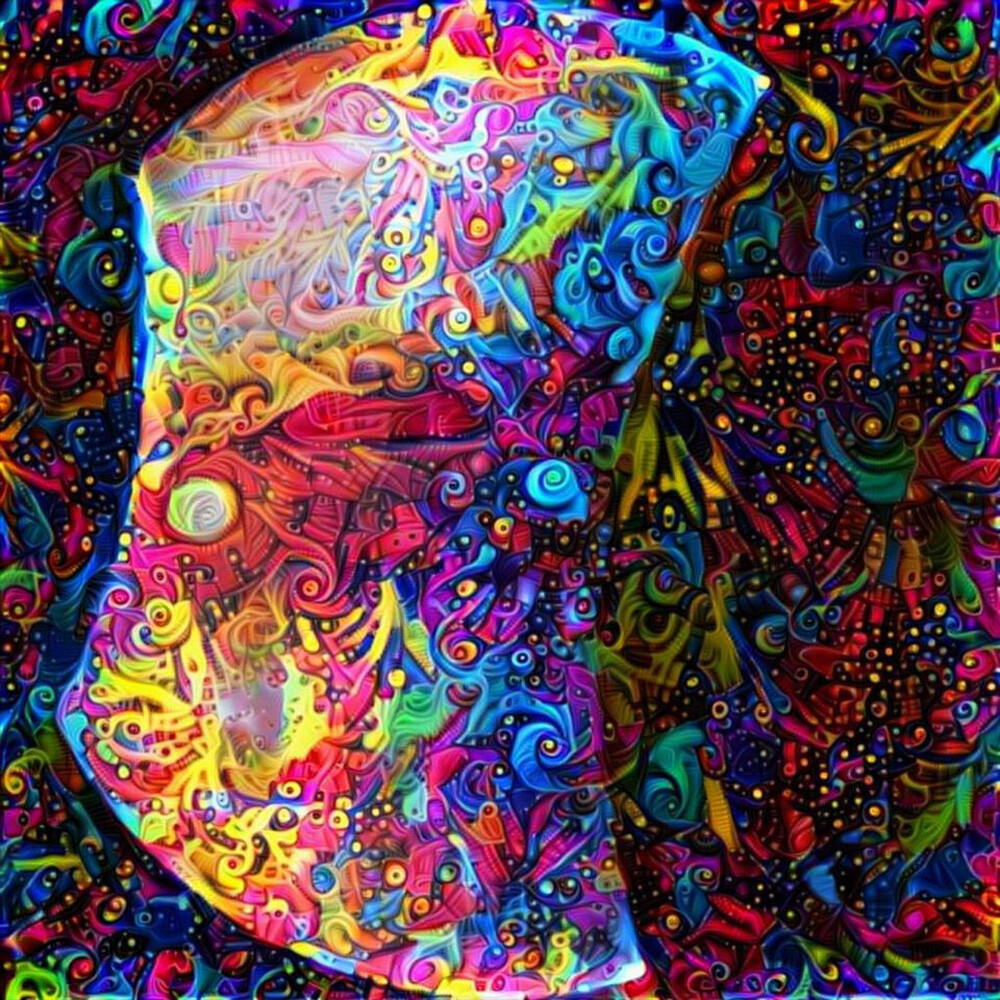

And artist Mik Petter did just that, turning Jupiter’s Great Red Spot (imaged 8,600 miles above its cloud tops) into a groovy, psychedelic piece that invites you to shoot DMT into your eyeballs and meld into its wild, otherworldly colors and shapes. Until you and the image became a single, ethereal entity and you’re peacefully floating through Jupiter’s swirls and its whipping, 900 mph storms:

Mik Petter creates trippy digital art using fractals, or patterns that repeat at progressively smaller scales and therefore look the same whether you zoom in or out. And with all due respect to Petter’s unique style, his dreamy, transcendental repertoire looks like something from the pipe dreams of the bastard child of Vincent van Gogh and the TOOL cover artist.

Fractals are created mathematically to display an infinite variety and never-repeating designs that, like the 4.6-billion-year-old Jupiter itself, entreat you to consider the timelessness of the cosmos.

Nanoflowers

An engineering team at Harvard, led by Wim Noorduin (who is apparently named after a Skyrim elder dragon) has created the world’s tiniest flowers, each smaller than a human hair:

Despite the nanoflowers’ microscopic complexity and beauty, they’re easier to make (and require fewer chemicals) than a Betty Crocker sheet cake mix.

Even Noorduin says you can do it in the kitchen. Just dump some sodium silicate and barium chloride in a beaker full of water. As the mixture dissolves and reacts with carbon dioxide from the air, barium carbonate crystals form on a glass slide submerged in the beaker. The flower’s delicate, varied features take shape as the crystals are pushed and pulled by the constantly shifting chemical and pH gradients.

The nanoflowers are amazingly fragile, and just walking near the beaker can disrupt them. But by carefully making minor tweaks, like increasing the CO2 concentration, altering the temperature, or reversing the pH, induces the formation of broad, leaf-like structures or the curved ruffles of a nano-rose.

If the simplicity seems underwhelming, that’s the point. Inspired by nature’s ability to effortlessly create an infinite variety of self-shaping structures, Noorduin sought a simple chemical process to do the same. In fact, the research probably required less effort than naming the study: Rationally Designed Complex, Hierarchical Microarchitectures.

To get a better sense of the flowers’ insanely Lilliputian dimensions, you should check out a bunch of them at the feet of the Lincoln Memorial. Not the Lincoln Memorial where politicians secretly broker billion-dollar deals that send your kids to war, the Lincoln Memorial on the back a goddamned penny.

Top Image: Mik Petter