6 Insanely Specific Causes People Devoted Their Lives To

Most people live their entire lives without finding a cause to devote themselves to. Other people find that cause, but it turns out to be something asinine like Counter-Strike or water polo.

Each of the following folks has in their own unique way improved the world through their (sometimes insane) devotions, either by providing spirit-nourishing art, saving animals, or advancing medical science. Coincidentally, this is also a list of the coolest people in the world to have a beer with ...

Mike Geno, The Man Who Paints Cheese

Don't Miss

Mike Geno paints portraits, but he doesn't want to immortalize your grandpa in his Sunday best. Geno paints portraits of cheese. However, these aren't just simple cheese portraits. They have a captivating, meditative quality that reaches deep into the soul as if to say: "this is the human condition, represented in lactic acid, fat, and protein."

Philadelphian Geno is a college-and-graduate-school trained painter with experience in the meat-cutting business, which helped pay off his tuition. Geno first painted a "beautiful steak" and has since captured the essence of nearly 600 foods, especially sushi, donuts, bread, and bacon.

Though none of his other works have brought him fame like his cheese portraits, which strikes a chord with art aficionados, cheeseheads, and laypeople alike. He's created around 400 of them over the past decade, many by commission, others based on what caught his fancy at the market. And each one has its own magic, arresting your attention in some weird way that inspires close inspection and, after a moment, downright hypnotism.

In addition to the big money superstars, your cheddars, mozzarellas, and bries, Geno's Cheese Map of the United States raises awareness for obscure, small-batch cheeses from each state.

Able to seamlessly blend different styles, some of his still-lifes boast a timeless, van Gogh-like quality, with their thick, visible brush strokes and vibrant, emotion-piquing colors. They transcend mere culinary considerations and reflect our own thoughts and insecurities. And, like this cheesecake, remind us of how fragile and tiny we are on a cosmic scale:

And it can be yours for only $550. Other paintings, intentionally or not, exude the Bacchanalian sexuality of a Renaissance masterpiece, condensed into a single food item, tiny in size yet colossal in feeling. Be it this deflated, oozing donut hole caught in a moment of shameful, post-coital contemplation:

Or these sperm-like caper berries, bursting with life and vitality:

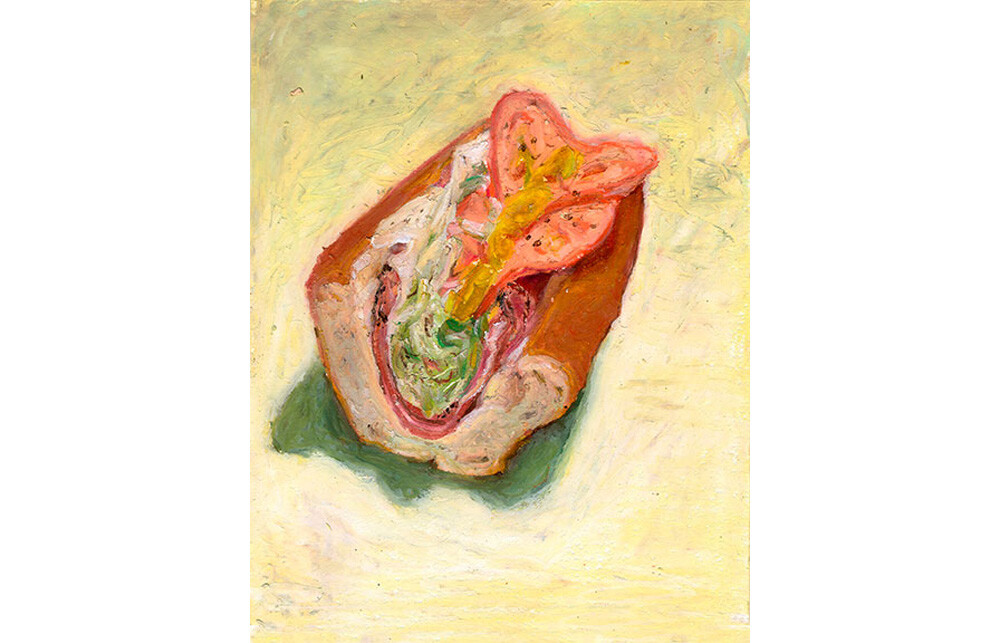

Or this "hoagie half," unabashedly revealing its contours and flaps because it's perfect just the way God made it:

And that's the beauty of Geno's food portraiture. It inspires so many diverse emotions you have to take a step back and analyze them one by one. Who knew looking at cheese could be such a cathartic, spiritual experience.

Bill Lishman, “Father Goose”

Bill Lishman was very much the "eccentric artist" archetype. He was kicked out of high school for a dynamite-related incident, invented a metal pipe rocking chair, and built an underground dream home carved into the side of a hill and composed of circular rooms (because he didn't think that people should live in boxes). He also erected two Stonehenges, one made from smashed-up cars and the other out of ice, because he felt the shape provided a cosmic conduit to arcane, universal knowledge.

He also made these.

But Lishman became known as "Father Goose" for his efforts to lead birds on safe migratory routes in his home-built ultralight aircraft. Flying his DIY death-trap (like a flying lawn chair, but with even fewer safety features) in the early 1980s, he was briefly joined by a flock of ducks numbering in the thousands, according to Lishman's estimates. They were so close that he could see every feather and every muscle twitch. This ain't half-bad, he thought to himself.

Lishman described it as the most meaningful moment of his life. And set about to recreate it, kicking off a decades-long fascination that would see him fly with countless birds and lead many others on safe migratory routes. Lishman began by "imprinting" geese, making them think he was their father. Bird imprintation is not particularly difficult (though it only works with large, precocial birds like ducks, geese, and swans) because the babies think the first thing they see is their parent.

First, Lishman taught birds to fly alongside his motorcycle by presenting it to hatchlings and firing up the engine to habituate his feathered children to the noise. You thought that neighbor with the drum kit was annoying? Imagine someone revving their bike up and down your street with a flock of squawking geese in tow. Lishman then replicated the technique with his ultralight.

He eventually moved onto the insanely endangered whooping cranes, whose numbers dipped below 20 in 1940. They numbered in the 400s in the 1980s, and Lishman hoped to lead many of them to their migratory grounds, which involved a 3,000 mile-long trek between Texas and northwest Canada. He also led a second flock on a Wisconsin-to-Florida migration route as insurance, just in case a 747 turbine shredded the first flock. This alternate route consisted of about 1,200 miles and took 35 hours by ultralight craft, which are constantly grounded by finicky weather conditions.

Imprinting the ultra-endangered whooping cranes was trickier. Lishman and his conservationist friends had to wear a "crane burka" (a big white bag with a screen), play crane sounds, and brandish a hand puppet. They wanted the cranes to retain their instinctual fear of humans and to remain wild, ensuring they avoided settlements. And also that they maintained their birdly sexual instincts and didn't try to mate with their human guides.

Lishman's enterprise inspired the 1996 Jeff Daniels vehicle Fly Away Home. A film that took many liberties in dramatizing Lishman's journey, including killing off his wife in the first scene.

Ah, good ol' predictable Hollywood, once again relying on the classic dead wife motivational story.

Arthur Boyt, The Man Who Eats Roadkill

Cornwall resident Mister (knighthood pending) Arthur Boyt has become famous for eating roadkill. And, by clearing carcasses from England's motorways and hedgerows, has performed a more useful service than any the monarchy has provided lately. And unlike the snobby royalty, Boyt doesn't find it a faux pas to scoop a mangled badger from the side of the road and turn it into a Christmas casserole.

Boyt, a retired marine biologist and animal welfare proponent, prefers eating animals that haven't been purposely killed but met a more natural demise under the carriage of a Vauxhall. And the octogenarian has been eating salvaged animals, including otters, hedgehogs, weasels, bats, polecats, and various fowl, for almost 70 years.

Plus, Boyt saves a bunch of money because the world is his supermarket, and he's potentially food shopping wherever he goes. He's plucked countless pheasant corpses from hedgerows and, while at the beach, once ran across a dead dolphin and thought, "There's a lot of good meat on that." So he took it home, possibly half-wrapped in a tarp with its bloody tail and snout dangling off the front and back of Boyt's little Mr. Bean car. Nothing personal against Boyt; we just imagine every English person driving those.

Boyt described the fried-up dolphin as quite tough but not particularly fishy or oily. And in 2016, he hit the jackpot when a bloated sperm whale washed up and supplied him with years' worth of meat and blubber.

He doesn't use spices or seasoning but gets creative with his recipes, cooking up blackbird pies and otter risotto (Boyt calls it "risotter"). He's even tasted the forbidden meats: cat and dog. He always makes a great effort to reunite the dead cats and dogs he finds with their owners, but unidentifiable strays are fair game.

Like the labrador and two lurchers, he found on a road near a camp. With no collars, and the campers uninterested in helping him locate the animal's potential owners, Boyt turned them into dinner. The lurchers, especially, had "lots of lovely meat."

And he wastes nothing. Food that turns foul(er) is left out for the foxes that visit his 16th-century farmhouse, which sits on an abandoned airfield in Bodmin Moor. But, despite the rotting whale steaks, holiday badger casserole, and lurcher burgers, Boyt somehow ended up married to a vegetarian. And on the fated day that the reaper comes a-calling, Boyt wishes to complete the circle of life and return to the earth the same way he lived, allowing his body to be scavenged by vultures. Hakuna Matata.

Lynea Lattanzio, The Ultimate Cat Lady

What's the cutoff for "cat lady" status? Six cats? 10? How about nearly a thousand. Lynea Lattanzio is the queen and patron saint of cat ladies. And founder of The Cat House on the Kings, "California's largest no-cage, no-kill, lifetime cat sanctuary and adoption center," which spans 12 acres along the Kings River in Parlier, California, and, as you might have guessed, houses cats

Lattanzio vehemently opposes kill centers and the all-too-many breeders that crank out labra-doodles on assembly lines while countless neglected animals are euthanized. These practices make us a third-world country, she argues, and, well, she's got a point. So, since founding the cat house almost 30 years ago, she has helped save more than 8,000 dogs, nearly 40,000 cats, and has spayed and neutered almost 60,000 animals to combat overpopulation and prevent Fresno from turning into one of those Japanese cat islands.

At first, Lattanzio maintained the cat house out of her own pocket. She sold her diamond wedding ring (and replaced the husband himself with hundreds of cats), spent her retirement fund, and sold her Mercedes and Cadillac. Lattanzio also gave her 4,200-sq-ft, 5-bedroom house to the cats and now resides in a trailer ... which is also full of cats.

Nearly 100 employees, techs, and volunteers ensure that the rescued cats (between 700 and 1,000 at any time) are vaccinated, micro-chipped, and treated for fleas, worms, and other feline-plaguing pests. There are multiple shelter areas (with HVAC for kitty comfort), including one for shy cats, one for sick cats, one for kittens, and another for older cats that are tired of everyone's shit. There are also two ICUs where Lattanzio and staff heal and revive the sick and injured.

The heavy daily workload begins at 4 a.m. with feedings and wiping the runny noses and eyes of the poor kitties suffering from feline herpes. And, per week, the cat house scoops up 900 pounds of litter and doles out 1,100 cans of cat food and 1,500 pounds of kibble.

Gigantic piles of laundry and cartoonishly tall stacks of food and water bowls are washed daily, accounting for a weekly expenditure of 10 gallons of detergent and 7 gallons of dish-washing solution. All combined, it costs about $1.6 million a year to run the facility.

And as a 501(c)(3) non-profit corporation, it doesn't receive any government or public funding. So the cat house depends on donations and offers various options to help. You can sponsor a cat, provide wish list items, donate that old Ford Pinto before it immolates you, commission a memorial plaque or bench, and even bequeath that Gamestop stock you bought because Reddit promised you a financial revolution. And after all the cat videos and memes you've consumed, you owe it to the cat house to chip in a few bucks.

James Niehues, The Dude Who Makes All The Ski Maps

All those ski maps and posters we have in our collective memory, which we assume were made by some kind of robot, look so similar because they were made by one guy. James Niehues is that guy.

Over the past 35 years, Niehues has painted more than 430 total maps on five continents. This includes well over 200 trail maps for instantly recognizable ski spots like Vale, Heavenly, Squaw Valley, Mammoth Mountain, and all the other famous locales you hear about on the news whenever a skier goes missing.

Niehues came of age on a farm in Loma, Colorado, where he curated and spread manure. He began painting during high school while bed-ridden with kidney inflammation. Then in 1987, while working at a Denver print shop, he met Bill Brown, the Old Master of ski map painting. Brown, planning to retire, put Niehues on a job for Mary Jane mountain in Winter Park, Colorado, and so became Palpatine to Niehues' Vader.

Ski resort trail map painting is a one-person niche. So once Niehues inherited the mantle from Brown, he became the guy. Plus, he was good. Damn good, with a knack for capturing the soul of a mountain. And all its uh, titillating, sensual features.

During a good year, he'd paint more than 20 pieces, following a meticulous process that can take upwards of three weeks. Niehues paints each individual tree, dimple in the snow, and mountainous nook and cranny. To ensure accuracy, he consults photographs, topographical maps, satellite images, and often flies over the trail to take aerial photos.

If he was working a regular job, Niehues would wake up at 3 a.m. to paint. And at his feverish, creative peak, he worked as many as eight hours a day, seven days a week. When his entire body cramped, his shoulder failed, and he could no longer hold up the brush, he rigged a sling from the ceiling and kept painting.

Work temporarily dried up due to the computer-generated mapmaking boom of the 2000s. But machines could never replicate Niehues' ethereal touch and timeless quality; the way he paints it, you'd think each chairlift had been there since time immemorial. Prices range based on the size and frugality of the client. But even the swankiest resorts usually paid between $1,800 and $16,000 per commission — the money-scrounging, shareholder-pleasing practice we expect from places that charge $5 for a mini-bar Milky Way.

Niehues, once a (self-described) intermediate skier, no longer partakes. He does hike, though, and may rely on his insanely detailed work when searching for the best branch to climb to escape a hungry grizzly. He also goes down in history as the only person (probably) to make the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame using only a paintbrush.

Steve Ludwin, The Guy That Injects Himself With Snake Venom

Former indie band punk-rocker Steve Ludwin has been envenomating himself with toxins from some of the world's venom-iest snakes for more than 30 years. He doesn't let the snakes bite him; that would be crazy. Instead, he "milks" them (this doesn't hurt the snake) and injects the venom. Or drinks it. Or drips it into an open incision. Why? For shits and giggles at first, then for its supposed anti-aging effects, and now for medical research and potential life-saving purposes.

Ludwin is a lifelong snake aficionado who started collecting serpents at the age of five in his native Connecticut. Then, at around 10 years old, he met the famous venom-injector Bill Haast. And like that Singaporean kid meeting Michael Phelps, Ludwin knew he would follow his hero's example.

He first dabbled in 1988 while working his dream job at a vivarium in London, where he handled snakes, spiders, and lizards. Luckily, his boss didn't mind him taking the snakes home for milking. Ludwin has since been injecting venom at different intervals. Sometimes every few days, sometimes weekly. It's an energy boost, like drinking coffee, he says, sometimes before heading out to literally dodge London traffic on his skateboard like Frogger.

Ludwin has had multiple bad reactions. Once, he suffered a cobra venom-induced heart attack. Then, for a while, his leg began to rot and was dotted with festering, "decomposing stinkholes" that "stank like death" and attracted flies like a sugar-coated dog turd on a hot day. And he brushed cheeks with the grim reaper after overdosing on a home-brewed cocktail of three different venoms. His hand swelled like a baseball mitt, and he calmly realized he might die right then and there as he sat watching David Attenborough and eating Chinese food.

The next day, he went to the hospital when his arm became a red, doughy liquid-filled sack with bulging blood vessels. He spent three days in the ICU with no improvement and discharged himself. A week later, he amazed doctors by not being dead or even losing his arm — it looked like his immunization effects were working. Ludwin continues his self-envenomation, to which he attributes his youthful appearance, tennis skills, fitness, and immunity to colds and flu.

More recently, he's been working with scientists at the University of Copenhagen, who are deriving antibodies from his blood and bone marrow. The latter of which had to be drilled from his spine and required two months of recuperation. Hopefully, this "Ludwin Library" may supply the first widely used human-derived anti-venom. Thus, ending the need for animal experimentation and decreasing the risk of potentially fatal allergic reactions in humans who receive animal-derived doses.

So say what you want about Lundin's practices and beliefs, but ask yourself this: when's the last you made yourself useful to medical science?

Top Images: Tontan Travel/Flickr