The Dark History Of The Texas Rangers (Hollywood Leaves Out)

You can’t spend much time in Texas without seeing a reference to the Rangers. No, not the baseball team, which should have disbanded the moment their 2015 season ended in complete humiliation. They borrowed their name from the law enforcement agency, which has popped up everywhere from The Lone Ranger to Walker, Texas Ranger to Fallout: New Vegas. While state police forces exist throughout America, the Rangers are the oldest, most mythologized, and the most messed up.

CBS

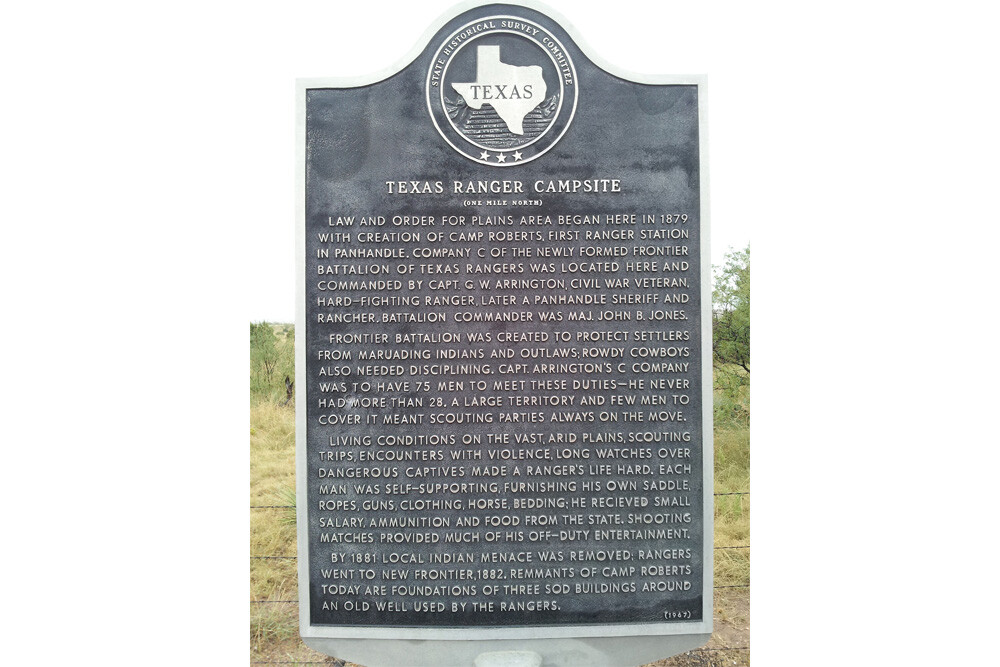

The Rangers trace their history back to 1823, when a few men were hired to protect new settlers, but they were officially founded in 1835. Their initial role was to protect Texans from outlaws and native raids, and they served in battles against Mexico. Today they have more typical law enforcement duties, but from their earliest days they were portrayed as an incorruptible force of civilization.

Don't Miss

And that’s the image they still project today. Chuck Norris’ Walker was a hokey morality play about the perfect man using karate to stop generic bad guys. You can buy hagiographic books like The Ranger Ideal and Lone Star Justice, or romances like Texas Ranger Heroes if you need cowboy cops in your bathtub and wine night. Their official history discusses their “toughness” and “ferocity” amid life or death struggles, essentially reducing them to a series of badasses with badass nicknames doing badass things. A semi-official motto/brag based on an apocryphal story is “One riot, one Ranger.”

Rangers have been a pop culture staple for a century, starring in oodles of TV shows and movies and books and radio dramas, always the picture of rugged, reliable masculinity. But that official government history also casually mentions the military “methodically ridding Texas of its Indian problem” and, well, you can imagine how the Rangers might fit into that.

Those 1823 proto-Rangers were hired by Stephen F. Austin, the “Father of Texas,” who said natives were “universal enemies to man” and “There is no way of subduing them but extermination.” And that’s pretty much what the Rangers contributed to. The Rangers would execute hundreds, maybe thousands, of natives, which wouldn’t make for a great Chuck Norris vehicle.

Ranger lowlights include the 1826 massacre of approximately 50 fleeing Karankawa at a place later dubbed Dressing Point (because the natives had received the “dressing they deserved”), the 1840 betrayal and murder of 35 Comanche diplomats and civilians, the 1848 killing of 26 peaceful Wichita and Caddo hunters, and the 1860 murder of 14 unarmed Comanche. We guess “several Rangers, many executed innocents” isn’t as pithy of a slogan.

Such massacres would often be hastily reframed as heroic battles, but some of the actual battles the Rangers fought were dubious too. 1858’s Battle of Little Robe Creek saw the Rangers defy federal law and trespass on protected Indian Territories to attack the Comanche. The Comanche had responded to continued encroachment with brutal raids (see betrayal and murder of diplomats, above, to get a sense of their mood), but if your response to enslavement and rape is “We should try something like that” it’s hard to paint yourself as the good guy.

The Rangers were led to that battle by the mythologized John “Rip” Ford. While Washington frowned on the Rangers defying the law, they later adopted many of Ford’s tactics, including indiscriminate slaughter, the targeting of women and children, and the destruction of food supplies. The Ranger Hall of Fame notes that Ford “defeated the Indians in two battles,” while the Bullock Museum dryly says that Ford “crossed the border without permission” before using “superior firepower” to kill 80 Comanche.

via Wiki Commons

Mexicans didn’t fare any better under Ranger rule. A young Ulysses S. Grant noted that, during the Mexican-American War, the Rangers felt a “right to impose on the people of a conquered city to any extent.” They looted, raped, and murdered. Ranger Sam Walker, upset at how he had been treated during captivity in Mexico, summarily executed several captured Mexicans accused of crimes. News and tourism sites dodge that as they laud Walker’s heroism.

During the Mexican Revolution, lynchings and murders by the Rangers were common, with victims handwaved away as “bandits.” In 1915, the Rangers falsely accused 10 Mexicans of robbing a train, then immediately executed eight of them. And in 1918, in response to a spate of cattle raids, the Rangers grabbed 15 unrelated Mexican-American men and boys and shot them. Civil rights activist and Texas state legislator Joe J. Bernal summed up the Rangers as “Mexican Americans’ Ku Klux Klan.”

The downplaying of the sheer brutality of frontier America began during frontier days. Just like today, sensational, uncritical stories of heroic law enforcement adventures made for easier reading than grim talk of nihilistic massacres. They often were heroes; the frontier was awash with crime, and while their tactics could be nasty there is no doubt that they stopped some rather nasty people. The list of Rangers killed in the line of duty is dominated by the Old West days.

Official history says the Rangers dealt with “bloody feuds, lynch mobs, cattle thieves, barbed wire fence cutters, killers and other badmen,” and that they “contended with local disturbances that amounted to miniature wars.” There’s a certain whimsy to it, like back in the good old days the heroes just had to keep shooting the “badmen” until all their problems were solved. For all the Rangers’ brushes with death they sure make law enforcement sound morally simple.

via Wiki Commons

But it’s pretty clear what the good guys looked like to the Rangers. They broke strikes and unions, and they hunted, beat, and sold escaped slaves, often ignoring borders in the process. At one point they entered and sacked the Mexican town of Piedras Negras for harboring escapees. A news site dubbed the Ranger captain behind that expedition, James Hughes Callahan, a “forgotten hero.” Sometimes defending white America meant stopping violent cattle rustlers, and sometimes it meant committing what we’d now call war crimes.

The Rangers tried to run the NAACP out of Texas in 1919, and they didn’t improve much during the Civil Rights era, at one point arresting black students despite a court order to let them attend school. That could be a whole separate article, but the time in 1963 when Juan Cornejo, the new Latino mayor of Crystal City, criticized police violence and a Ranger captain responded by smashing his head into a wall sums it up. Oh, and that was after the captain tried to intimidate Latino voters by assaulting activists, raiding Latino businesses, and enforcing a curfew on Mexican-Americans.

The Rangers didn’t have a Black officer until 1988, and didn’t have women until 1993. Both were only accepted after significant outside pressure. Their modern history is as checkered as any police department, featuring good (busting open a major sexual abuse scandal, clearing painful cold cases) and bad (letting a murderer falsely claim hundreds of other victims as an excuse to close cases, getting sued for ignoring just a whole ton of misconduct). But last we checked the modern Rangers weren’t setting Mexican settlements on fire, so what does their past have to do with anything?

Well, the Rangers are presented as having a storied history that stretches back for centuries, but whenever the bad bits are brought up they’re dismissed as not counting because they’re so old. Celebrating the good while trying to pretend the bad never happened is a microcosm for American history, but the idea that an arbitrary line can be drawn is wishful thinking. How do you function when your history includes racism and slaughter? You can either acknowledge it or ignore it, and you can probably guess what Texas Republicans have done.

Attempts to recognize Ranger massacres have been met with resistance and denial. In 2020, Governor Abbott took time out of his busy day to go on Twitter and call for a grade eight teacher to be fired because he drew a through line from slavery to modern police brutality. More recently, Abbott railed against the vague boogeyman of critical race theory before signing a bill that limits how the freest state in the freest country can discuss race and current events in the classroom. (America and the Rangers are obviously so great that we don’t need to listen to any interpretations to the contrary.)

Frank Hamer, another member of the Ranger Hall of Fame, had some memorable moments in his career, including leading the hunt for Bonnie and Clyde and protecting prisoners from lynch mobs. He also posed for a postcard featuring the bodies of lynched Mexicans, and threatened a representative behind a 1919 investigation into the Rangers denying prisoners their rights, torturing and murdering captives, and committing massacres. That inquest is considered a landmark in exposing police corruption … and in not doing much about it. A century later, a Netflix movie tried to tackle Hamer’s complicated history by making him a brooding antihero and calling it a day, like implying that he meant well when doing bad stuff would be good enough.

Netflix

And that’s the thing about mythology, about uncritically accepting fables of heroic military feats and cartoonish enemies that want nothing from their life but to destroy yours. If you let tales of impossibly good people form your worldview, you don’t leave any room for nuance once reality shows up and starts poking its inconvenient holes. That’s how attempts to remind people that racial massacres are bad can get furiously dismissed as opportunistic “politics,” how suggestions that maybe history affects today get called part of an evil conspiracy. If you let something get built up as much as the Rangers were, you end up with a big problem once the edifice starts to crumble.

And, again, the baseball team sucks.

Mark is on Twitter and wrote a book.